Bacteriophages in Georgia

Georgia hosts a unique scientific institute where bacteriophages—viruses that destroy bacterial cells—are studied. Bacteriophages (or simply “phages”) essentially serve as antibiotics. However, there’s still insufficient scientific research on them, so you won’t find phages recommended for treatment. But experts claim this is temporary. With bacterial resistance to antibiotics increasing annually, scientists believe the future lies with phages. In this regard, there’s much for the world to learn from Georgia.

Chris Schafer’s life changed completely on the eve of Christmas 2018 in California. He required urgent surgery due to a perforated colon. The surgical intervention led to several complications. Due to prolonged antibiotic treatment, Escherichia coli bacteria in his body produced beta-lactamases, rendering them resistant to antibiotics.

Bacterial resistance to antibiotics means bacteria adapt to the drug, rendering it ineffective.

“I couldn’t even go to the bathroom, I felt really bad. I took antibiotics. The period when I had no symptoms without antibiotics gradually shortened, and eventually, I reached a stage where symptoms recurred within 1-2 days after stopping antibiotic intake,” Chris Schafer recalls.

American doctors believed the only solution was intravenous antibiotic administration. Chris remembers that this procedure required hospitalization, and doctors couldn’t guarantee its effectiveness. That’s when he decided to independently seek alternative treatment methods.

His search led him to phages—specific viruses that only destroy certain bacteria, and once the quantity of these bacteria diminishes, the phage “voluntarily” leaves the body. Unlike phages, most antibiotics have a broad spectrum of activity, meaning they kill both harmful and beneficial bacteria in the body.

No one in Chris’s circle, including American doctors, knew anything about bacteriophages. For months, he researched this topic and sought out people whose lives had been changed by phage therapy. Finally, he decided to come to Tbilisi.

▇ Today, medicine faces a significant problem: frequent and improper use of antibiotics has led to resistance against them.

Chris Schafer in Tbilisi. Photo from his personal archive

Chris Schafer in Tbilisi. Photo from his personal archive“As an American, I was initially very skeptical. I thought that if I met these people in person and talked to them, I would understand whether this was true or just a scam.

And now, I want to tell you that the Eliava Institute exists [The George Eliava Institute of Bacteriophages, Microbiology, and Virology in Tbilisi — JAMnews] and phages really work,” Chris says.

Chris arrived in Georgia on June 5, 2022. Four months later, phage therapy produced results that couldn’t be achieved in two years of antibiotic treatment.

Chris returned to normal life and asserts that phages saved him:

“Today, I am alive and believe one hundred percent that if I hadn’t gone to the Eliava Institute, I wouldn’t be alive to talk to you now.”

Antibiotics – a global healthcare problem

The George Eliava Institute of Bacteriophages, Microbiology, and Virology was founded in 1923. The institute quickly gained popularity, and phages for treatment were delivered from Tbilisi to several countries in the Soviet Union.

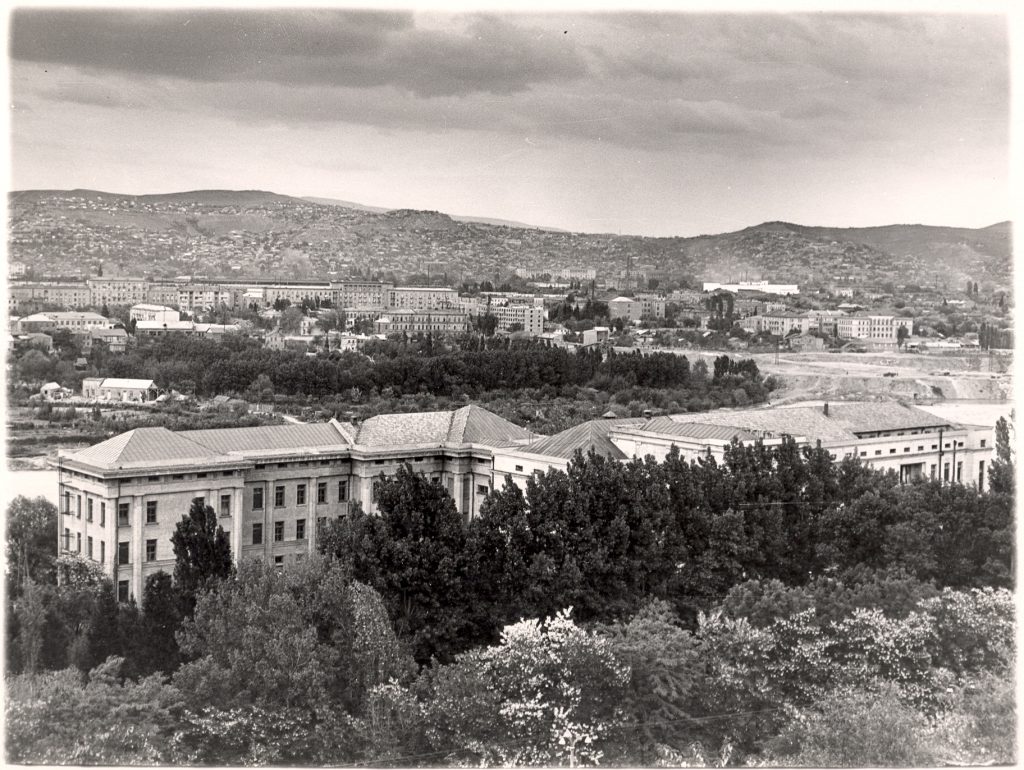

The Eliava Institute building, mid-20th century. Archive photo

The Eliava Institute building, mid-20th century. Archive photo

At that time, interest in phages in the West was not as significant. The focus was on recently discovered antibiotics, which revolutionized medicine, and it seemed that the battle against bacteria was definitively won.

The Eliava Institute Laboratory in the 1960s. Photo from the institute’s archives.

The Eliava Institute Laboratory in the 1960s. Photo from the institute’s archives.

Indeed, antibiotics have saved millions of lives. However, over time, medicine has faced a new problem – frequent and improper use of antibiotics has led to resistance against them. This is precisely what happened to Chris and thousands of other people around the world.

Bacteriophages in Georgia

Antibiotic resistance stands as one of the foremost challenges facing global healthcare today. According to a study published by the World Health Organization (WHO) last year, 1.27 million deaths worldwide in 2019 were directly linked to infections resistant to antibiotics. It is estimated that by 2050, this figure will reach 10 million annually.

Against this complex backdrop, scientists are considering bacteriophages as one of the promising alternatives.

The World Economic Forum included phages among the top ten best new technologies of 2023.

Interest in phages is gradually increasing – research is being conducted, and production is being launched. In this context, Georgia, with its centuries-old experience in phage usage, is increasingly attracting attention from scientists worldwide.

The Eliava Institute

Before becoming the director of the Eliava Institute, Mzia Kutateladze had a long career path, which began at the same institute as a laboratory assistant. According to Mzia, although the institute was founded during the Soviet Union era, Western partners have made significant contributions to its development:

▇ “The institute would not have survived the 1990s without the assistance of foreign funds,” says Mzia Kutateladze.

The Eliava Institute has received funding in the form of grants from American and other international organizations, such as the International Science and Technology Center, the U.S. Civilian Research and Development Foundation, and the U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency.

“I remember when in the early 1990s, the then-president Eduard Shevardnadze came to the institute and said that the country could no longer afford to maintain it because it required significant funding. It was decided that the production part would be privatized by the employees, while the scientific part would remain under the protection of the state. This caused a lot of dissatisfaction. As a result, the component for the production of biopreparations was sold at a very low price,” Mzia Kutateladze recounts.

The staff of the Eliava Institute in the 1990s

The staff of the Eliava Institute in the 1990s

Many Western scientists were interested in Georgian phages. Thanks to collaboration with them and financial support from the West, the institute managed to save its phage collection. Then the first Western patient appeared, followed by hundreds of others.

“In 2000, the first Canadian patient came to us. He had a very severe condition: osteomyelitis of the joint developed after a car accident. After phage application, the infection disappeared, and he was able to move freely again,” recalls Mzia Kutateladze.

David Sturua, Director of the International Phage Therapy Center at the Eliava Institute, says that awareness of phages is growing every year. The institute receives patients from 84 countries.

David Sturua and Mzia Kutateladze at a scientific conference

David Sturua and Mzia Kutateladze at a scientific conference

According to him, the Eliava Institute has established a consortium that combines scientific, medical, and diagnostic laboratory components, as well as phage production and pharmaceuticals.

“Nowhere else is there such a comprehensive and advanced structure. In some countries, only the three-component system is developed, while in others, phage production is being developed, or they are used in some cases. Here, in Georgia, we offer all services together, which is very convenient for foreign patients.

The Eliava Institute and its associated institutions extensively study bacteriophages, producing broad-spectrum phages that kill many different bacteria while remaining stable,” says David Sturua.

Georgian know-how

Despite phages not being licensed yet, competition for their production is gradually increasing. The world is only now trying to develop phage therapy standards.

According to Mzia Kutateladze, against this backdrop, several organizations interested in studying the Georgian experience have approached the Eliava Institute.

The Eliava Institute building today. Photo by Khatia Shamanauri

The Eliava Institute building today. Photo by Khatia Shamanauri

Mzia Kutateladze explains, ‘A phage should kill as many different bacteria as possible, its range of action should be as wide as possible. Our staphylophage kills 85-90 out of 100 bacteria. This is a very high rate.’

According to her, there are often cases where an existing, ready-made drug does not work, and the institute has to produce new phage preparations for individual use.

‘Sometimes bacteria develop new defense mechanisms against phages, so we have to find a new phage or ‘teach’ the existing one to bypass this defense. But unlike antibiotics, isolating and selecting effective phages against new resistant bacteria is much simpler and more efficient. And this is the know-how of our institute,’” Kutateladze says.

Foreign visitors at the Eliava Institute. Photo: from Mzia Kutateladze’s personal archive

Foreign visitors at the Eliava Institute. Photo: from Mzia Kutateladze’s personal archive

Thus, the staff at the Eliava Institute have managed to cure many patients. According to David Sturua, they had patients who had been taking antibiotics for 15-20 years, but only after switching to phages did the quality of their lives significantly improve. One such story is recounted, for example, in an article published in 2022 in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

Skepticism regarding phages

Although many leading Georgian doctors have been actively using phages since the 1990s, skepticism about this method is still significant. This is primarily because phage therapy is not yet sufficiently researched and licensed. It is for this reason that many medical professionals, including those in Georgia, avoid this method.

Mzia Kutateladze believes that such an attitude is explained by European recommendations followed by Georgian doctors, which do not mention phages:

“Phages are recognized by our [Georgian] regulatory body, but many follow European recommendations where phages are not legally recognized.”

According to Kutateladze, the main problem is that medicine does not yet know how to properly research phages. For a long time, all hopes were placed on antibiotics, and it was believed that there was no need for phages. However, the situation is changing now:

“There are no clinical studies defined by international standards in this direction. These studies require a lot of money and time. However, the situation is gradually changing, and, for example, in the United States, about 50 such studies are currently underway.”

Georgian infectious disease specialist, Doctor of Medical Sciences Maya Butsashvili, says that at this stage, she does not prescribe phages to patients because she believes there is insufficient evidence of their effectiveness. But she agrees that in the future, phages will become more in demand:

“In the end, this is a very promising topic. There is great interest not only in our country but also in the West. Antibiotics have reached an impasse, and our arsenal is slowly running out. Of course, medicine is looking for new directions, and in this regard, phages are very promising,” believes Maia Butsashvili.

She says that as soon as she sees phages in the medical guidelines of authoritative international organizations, she will immediately start using them.

Despite the century-long history of Georgian phages, they are still a novelty for some citizens of the country. A similar situation exists in many other countries where phage therapy is still in the experimental stage.

Chris Schafer says that no one in his circle has heard of bacteriophages. Therefore, shortly after returning from Georgia to his home in California, he made an important decision. After many years of working in the education system, Chris plans to retire and dedicate all his time to promoting phage therapy in the United States. He intends to share his story and experience with people who may suffer from similar health problems but have not heard of phages and the Eliava Institute in Georgia.

The project is funded by ICFJ through the Health Innovation Program