Krieg mit #Russland? Putins Getreue warnen vor #Georgien-Wahl – Opposition sieht „Chance genau jetzt“. Von Florian Naumann @flrnnmnn via @fr https://t.co/lWKTEDn5fA

— Notes from Georgia/South Caucasus (Hälbig, Ralph) (@SouthCaucasus) October 24, 2024

Day: October 24, 2024

Thousands Volunteer to Protect Votes in #Georgia’s ‘Russia vs Europe’ Elections. via @CivilGe #GEvote2024 https://t.co/bda6HqLAJd

— Notes from Georgia/South Caucasus (Hälbig, Ralph) (@SouthCaucasus) October 24, 2024

Observers at the October 26 Election

Independent observers are set to be present at all polling stations during the upcoming parliamentary elections in Georgia on October 26, both domestically and abroad. Initiated by non-governmental organizations, a new civic campaign has emerged alongside experienced monitoring missions, involving trained volunteers from diverse professions, ages, and interests.

Students and scholars, singers and actors, writers, immigrants, homemakers, and many others are getting involved. This unprecedented mobilization has been declared by civil society in response to low public trust in the government and the expectation that the ruling party, “Georgian Dream,” may attempt to falsify election results. Observers are seen as a key mechanism to protect the parliamentary elections from potential fraud.

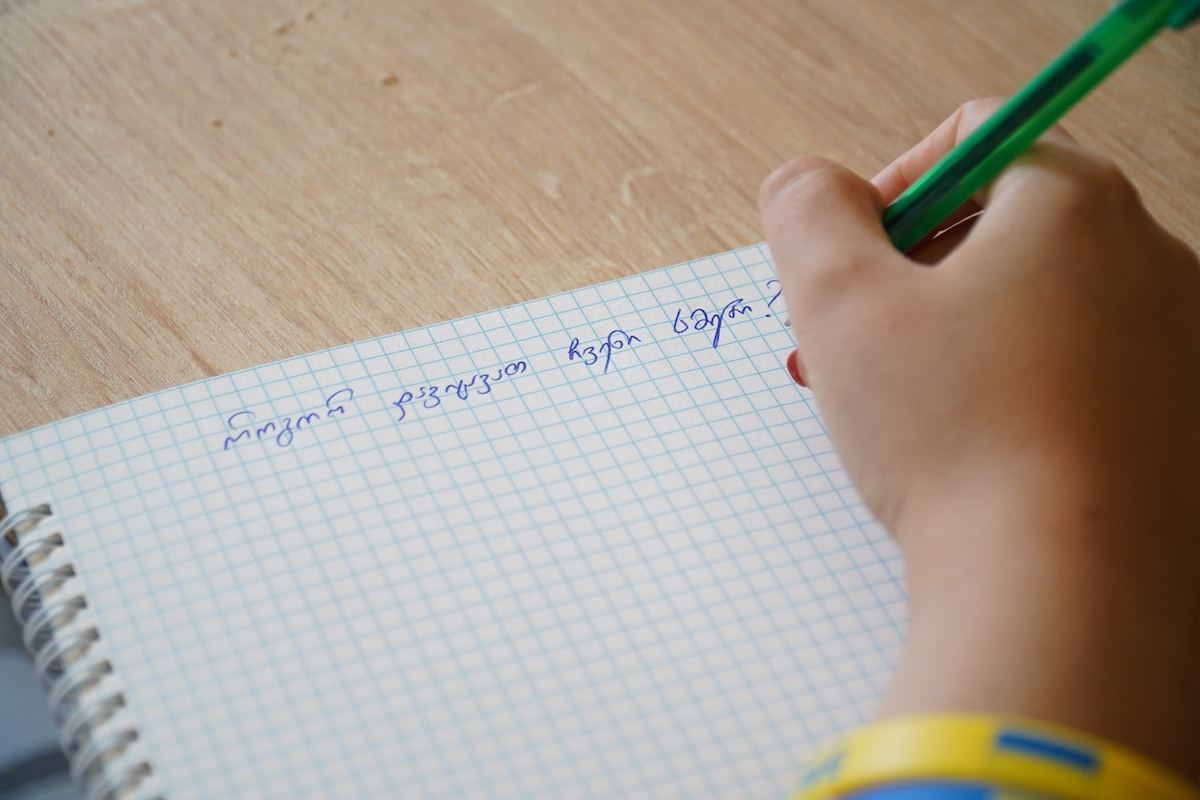

For 18-year-old Salome Kenchiashvili, this will be her first election in which she is eligible to vote. Salome was an active participant in protests against the “foreign agents” law and feels compelled to defend her and her fellow voters’ choices. This is why she has decided to become an observer.

“I don’t trust this government. I know there will be fraud, and we will do everything possible to prevent it,” says Salome.

To observe the voting process and vote counting on October 26, Salome connected with a group called “Observation,” created by civic activists. She registered and completed a series of training sessions to prepare for her new mission.

“I never imagined I would participate in the elections like this, that I would be so involved in it all. For the past two months, I’ve dedicated all my time to this, working hard to learn and gain experience.”

Many other Georgian citizens have made similar decisions. The exact number of observers will be announced a few days before the elections, but relevant organizations report that volunteers number in the thousands.

“I have been observing elections since 2006, and I don’t remember such unprecedented volunteer participation, with people not only ready to vote and protect their own voices but also to safeguard the votes of other citizens,” says lawyer Irma Pavliashvili.

The Tradition of Election Fraud in Georgia

Before almost every election in Georgia, the opposition and civil society call for “vote protection.” Fraud and the manipulation of election results by the government have remained pressing issues for many years.

This is why it is particularly noteworthy that in 2012, power changed hands through elections in the country—a first in Georgia’s independence. Previously, governments were replaced either by military coups or peaceful revolutions.

The first multi-party elections since 1919 were held in Georgia on October 28, 1990, even before the collapse of the Soviet Union. This decision came from an already weakened Communist Party in the face of a strengthening national movement and growing pressure from it.

At that time, the communists suffered a significant defeat.

“The communists were unaware of election fraud methods simply because elections were rarely held during the Soviet era,” says former parliament member David Zurabishvili.

He describes election fraud in Georgia as a “product” of the late 1990s:

“During the era of Eduard Shevardnadze, the second president of Georgia, quite severe forms of fraud were employed, including mass ballot stuffing and the hijacking of ballot boxes, as well as ‘carousel’ voting, where one person votes multiple times at different stations. Intimidation, bribery, and threats against voters were all part of the landscape at that time.“

One of the most significant political changes in modern Georgian history, the “Rose Revolution,” was sparked by election fraud: the results of the parliamentary elections on November 2, 2003, were clearly falsified by the unpopular Shevardnadze government, prompting opposition leaders and citizens to take to the streets.

Former parliament member Khatuna Gogoreshvili, who represented the “United Democrats” electoral bloc at the Central Election Commission (CEC), witnessed “carousel” voting and other tactics used to manipulate the results.

An OSCE report at the time noted that the media and local observers from the Young Lawyers Association and the International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy (ISFED) played a crucial role in increasing transparency in the process. The data they collected formed the basis for legal complaints.

“It was the observers who brought these protocols that allowed us to file complaints… Otherwise, how would we have known what the actual voting results were in any given area, and what was recorded as the final result?” Gogoreshvili said.

As a result of the “Rose Revolution,” Mikheil Saakashvili and his party, the United National Movement, came to power in Georgia, winning elections with relative ease in the early years. However, the results of the early presidential elections in 2008 remain contentious. These elections were preceded by repression against the opposition and media, as well as a political crisis.

Official results indicated that Saakashvili won in the first round, although the opposition claimed the CEC’s data was fraudulent. The National Movement categorically denied these allegations.

Reports from local NGOs varied significantly, while the OSCE mission stated that the elections generally met democratic standards, although serious issues requiring urgent attention were identified.

“The government practically had to resort to methods from the 1990s to secure a first-round victory,” recalls David Zurabishvili, who represented the Republican Party at that time.

Zurabishvili believes that after 2008, the approach in Georgian electoral tradition shifted: in his observation, the government focused on achieving the desired outcome during the pre-election period rather than on the actual voting day.

“When protocols are reviewed at polling stations, it becomes quite noticeable. To ensure that international observers would more or less recognize the legitimacy of the elections and that the government would achieve its goals, the emphasis shifted to securing election results before the actual voting,” he explained.

Attempts to influence the election outcome during the pre-election period typically involve the use of administrative resources, detailed voter registration through coordinators, bribery, intimidation of citizens, and more.

For many years, non-governmental organizations have reported concerns about the use of these practices, though violations identified on election day remain a major issue.

“The primary tension and political temperature escalate during the vote counting process,” says Irma Pavliashvili.

She recalls the 2012 elections, in which the ruling party at the time, the National Movement, suffered a defeat.

According to Pavliashvili, “all the methods that can negatively affect election results were used,” including the intervention of special forces in the vote counting at some polling stations.

However, she emphasizes that many attempts at manipulation remained just that—attempts—while others had legal consequences due to the activity of observers: “For this reason, re-elections were held in several districts.“

Despite the attempts at fraud, several factors determined the outcome of the 2012 elections, the first being record-high voter turnout, with over 2.2 million people casting their ballots—61.3% of registered voters.

The work of observers and NGOs also played a significant role, as did the willingness of President Saakashvili and the National Movement to acknowledge their defeat and transfer power. This is still considered one of Mikheil Saakashvili’s key political achievements.

The System Remains

Although power changed hands in 2012 and the new ruling party, Georgian Dream, promised unprecedented democracy, many of the corrupt practices from previous elections persisted.

“If we observe the electoral cycle, we see that the degree of systemic violations increases as government approval ratings decline. When popularity falls, efforts by a party often focus on maintaining power,” explains Irma Pavliashvili.

During Georgian Dream’s tenure, the most “notable” elections were the presidential election in 2018 and the parliamentary election in 2020, both of which were followed by accusations of fraud and protests from the opposition. In 2020, this escalated to an opposition boycott of parliament and a political crisis.

Due to an insufficiently fair electoral system, the use of administrative resources in favor of the ruling party, inaccuracies in final protocols, and other factors, the Young Lawyers Association of Georgia labeled the 2020 elections as “the worst organized elections” under Georgian Dream.

Elections 2024: What to Watch For

In 2024, elections will primarily take place electronically, though civil society emphasizes that this does not mean manipulation risks are fully neutralized.

The pre-election environment this year markedly differs from previous elections under Georgian Dream.

Under a law enacted a few months ago regarding “foreign agents,” the government has labeled local NGOs, including monitoring organizations and critical media, as “serving the interests of foreign powers,” and their donors as “foreign forces.”

Georgian Dream has promised that if it secures a constitutional majority, it will ban opposition parties. Meanwhile, the Prime Minister “reminds” the public that they have not lost any elections in the past 12 years.

Amid this rhetoric, it appears that Georgian Dream is unwilling to relinquish power and will attempt various means to influence the election outcome. While such attempts have become more apparent in recent election cycles, the NGO sector believes observers should remain vigilant on election day.

“Of course, this [electronic voting] doesn’t mean that manipulation will be impossible,” says ISFED lawyer Giorgi Moniava.

He is not alone in disputing the ruling party’s claims that the electronic model eliminates fraud. Tamta Kakhidze, an analyst with the international organization Transparency International, agrees:

“While the methods of fraud have become more complex, they are still possible if there isn’t an observer at the polling station who knows what to look for and pay attention to.“

Kakhidze outlines four main types of fraud that an observer can help prevent:

1. Voting with Someone Else’s ID Number

This method is applicable when a fraudster knows for certain that a specific voter will not show up on election day. In this case, the participant in the fraud registers in the system on behalf of that voter by entering their ID number.

“The observer should verify the data displayed on the verification device during voter registration. For instance, does the displayed photo match the person voting under that ID number?“

2. Voting with Someone Else’s Identification Document

In this scenario, “unreliable” voters are pressured or paid to temporarily surrender their ID, ensuring they cannot vote.

Instead, the fraudster takes the “confiscated” document to the polling station and votes on behalf of that voter.

Here, again, the observer must carefully monitor the registration process to ensure that the photo displayed on the screen matches the individual arriving to vote.

3. Tampering with Ballots

This can occur during the vote count. To be valid, a ballot must have only one circle filled in. A person involved in the fraud might secretly fill in another circle during the counting process to render the ballot invalid.

Therefore, the observer should ensure that no extraneous items—such as pens, markers, or pencils—are present on the counting table.

4. “Carousel” Voting

This traditional method involves a voter bringing a pre-filled ballot to the polling station and leaving with a blank one to pass along.

To prevent this, the observer should monitor the voting booth closely to see if the voter changes ballots. They should also watch for anyone photographing ballots, as this is often required by those pressuring or bribing voters.

“Unprecedented Mission”

On October 26, “Transparency International” will observe the elections alongside 29 other organizations under the coalition “My Voice,” which has pooled resources to train volunteer observers. According to the coalition, they received applications from 4,200 citizens, with about 2,000 set to monitor the elections across all electoral districts.

“I can say this mission will be unprecedented in scale,” declares Tamta Kakhidze.

The activist group “Observation” informed JAMnews that 300 citizens have undergone special training to serve as observers. An additional 300 will monitor the elections on behalf of the organization “Protect,” also formed by civic activists.

“Younger people are more engaged this year than ever before,” emphasizes ISFED Chair Nino Dolidze. ISFED will deploy around 1,500 observers both within districts and along the external perimeter, with mobile observation groups rotating between areas.

The Young Lawyers Association will have 600 observers, aiming to cover 1,500 districts through both static and mobile teams. Election logistics coordinator Giorgi Abuladze notes a heightened interest this year from citizens who have never observed elections before.

The deadline for organizations to submit their lists of observers was October 21, five days before the elections. Until the last moment, they encouraged citizens interested in participating to complete the necessary applications.

Salome Japiaashvili managed to submit her application and is now preparing for October 26.

“When the ‘Russian law’ [the ‘foreign agents’ law] was enacted, I faced two choices: to despair and leave the country or to continue the fight for a dignified life in my homeland. I thought about what I could do to contribute to this and decided that my role could be to observe the elections and ensure the protection of our votes,” she explains.

Observers at the October 26 Election

Nearly two-thirds of Armenians do not trust any politician – poll

Despite lack of faith in leaders, most think country is headed in the right direction. By Ani Avetisyan @AvetissianAn via @eurasianet https://t.co/m8SP8Np3t6— Notes from Georgia/South Caucasus (Hälbig, Ralph) (@SouthCaucasus) October 24, 2024

Kucera is wrong when he states that Georgian Dream is ‘heading right”. Since 2012 it dismantled Positive Non-Interventionism and established massive taxpayer funded subsidy of industry, corporate agribusiness and rural hospitality, with massive corruption, collusion & nepotism.

— Simon Appleby (@SirHumphrey1969) October 24, 2024

Georgia’s 2024 parliamentary elections will be the first time Shoghik Kurkchyan, 20, will be able to vote, and the first time she will observe the elections. A second-year banking and finance student at Tbilisi’s Ilia State University, Kurkchyan tells Civil.ge that she applied to a local monitoring mission to register as an observer to “help people vote fairly” and ensure that the overall process is fair.

Often described as a “referendum” on Georgia’s choice between Russia and Europe, the October 26 general elections are considered one of the most closely watched in the country’s history.

“This is the most important election ever held in independent Georgia, and therefore in Georgian history,” Lado Napetvaridze, a 35-year-old researcher, tells Civil.ge. This won’t be the first election for Napetvaridze, who has a Ph.D. in political science and teaches at Tbilisi State University, but October 26 will also be the first vote he’ll be monitoring as a registered observer.

Some three and a half million Georgians will be eligible to cast their ballots in the country’s first fully proportional vote that follows months of anti-democratic drifts by the ruling Georgian Dream party, including passing Foreign Agents Law and anti-LGBT legislation. The moves led to the suspension of the country’s EU integration process months after it became a candidate country, leaving pro-European and pro-democracy Georgians fearful of their country’s irreversible descent into authoritarianism.

Pro-Western opposition parties and coalitions will attempt to challenge Georgian Dream’s 12-year rule. But with the ruling party’s vast administrative, financial, and media resources, and the government’s escalating anti-LGBT propaganda, anti-Western conspiracies, and fear-mongering about Georgia repeating Ukraine’s fate of the Russian aggression, there is a widespread understanding that the race will be close, and the stakes will be high.

“I am worried about my university,” Kurkchyan says, expressing concern about the fate of Ilia State University, one of Georgia’s most popular higher education institutions, which has recently faced obstacles to its full accreditation. The trouble is widely believed to be part of a government crackdown on critical voices and institutions.

The elections worry many other younger Georgians as well, who are struggling to imagine their future in the country if the Georgian Dream remains in power.

The vote follows two widely contested elections in 2020 and 2021, in which local watchdogs expressed concerns that the level of violations during the campaign and on polling day – including alleged vote-buying, illegal mobilization efforts, and vote-counting irregularities – could have affected the final results.

Widespread fears that the ruling party might try to hijack the elections prompted thousands to volunteer to observe the vote and to apply to local monitoring groups. Everyone from first-time student voters to their professors, from a young piano prodigy to Georgia’s most famous opera singer has declared their intention to volunteer.

Missions Facing “Positive Challenge”

“It is very noticeable that a large part of the citizens not only want to participate in the elections but also want to observe,” Nino Dolidze, head of the International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy (ISFED), Georgia’s key election watchdog group, tells Civil.ge.

The deployment of observers has increased especially in the overseas districts, Dolidze notes. There were special efforts this year to increase the participation of expatriate voters, which has traditionally been insignificant despite the fact that hundreds of thousands of Georgian citizens live outside the country. 95,910 Georgians registered to vote abroad, about 45 percent more than in 2020, and while authorities did not open polling stations in various cities despite demand, there are active civic initiatives to help Georgian emigres with transportation on election day.

And unlike past elections, where observers were often assigned to random locations, this year’s observers are also more eager to exercise their right to vote, hoping to be deployed to polling stations where they are also registered as voters. “It is a positive challenge that all our observers want to vote,” says Dolidze, drawing a comparison with previous elections where this was less of a priority.

ISFED is one of more than 100 local organizations that have registered monitoring missions with the Central Election Commission (CEC). It plans to deploy some 1,500 observers inside and outside the country, and will again provide the results of the Parallel Vote Tabulation (PVT), a statistical method to verify the official results. More than 60 international watchdogs have also registered to observe the vote, including traditional missions of OSCE/ODIHR, as well as the International Republican Institute (IRI) and the National Democratic Institute (NDI), two U.S.-based nonprofits.

But while the number of registered organizations is about the same as before, mobilization on the ground looks more active than in past elections. Various initiatives and organizations such as “Observe”, “Protect”, and “Vote Guardian” have sprung up to train, inform, and deploy thousands of volunteers to protect the vote. In addition to the local missions that traditionally monitor Georgian elections, new ones have emerged, including My Vote, which unites dozens of civil society organizations and plans to deploy some 2,000 observers (selected from more than 4,000 applicants).

First Predominantly Electronic Vote

The October 26 vote will also be Georgia’s first election to be conducted largely electronically, meaning that voters will cast ballots at polling stations using electronic machines that identify and count the votes. 90% of voters in Georgia will cast their ballots using this new procedure.

While the new process is believed to reduce the risk of certain types of manipulation, there have been active information campaigns to educate voters about the changed way of casting a ballot (filling in a circle instead of circling a number) and about ways to avoid spoiled votes. There have also been efforts to reassure voters that their choices are anonymous, amid reports that the ruling party may be intimidating voters by suggesting that technologies store identity.

According to Dolidze, there are still risks of potential breaches that are not fully mitigated by new technologies, such as the possibility of a single person voting multiple times or casting a ballot for someone else. Also, “something could come up that we haven’t thought of,” ISFED chief says.

Based on electronic precincts, the CEC is expected to release preliminary official data later on election day, hours after the polls close at 8 p.m. local time. Final results are expected to be announced the following day after all ballots have been recounted by hand.

Until then, various activist groups have led active mobilization efforts, including calls to get out and vote, or initiatives to help commuting voters get to their polling places.

“Those around me who were never interested in politics are now planning to go to the polls and vote,” Napetvaridze says, arguing that the mobilization effort is not limited to volunteer observers. Both Kurkchyan and Napetvaridze expect to be able to cast a ballot in their respective constituencies – in Ninotsminda, Georgia’s southern Samtskhe-Javakheti region, and in Tbilisi – while they also observe the election.

Nini Gabritchidze/Civil.ge

Also Read: