By Andrew Byers

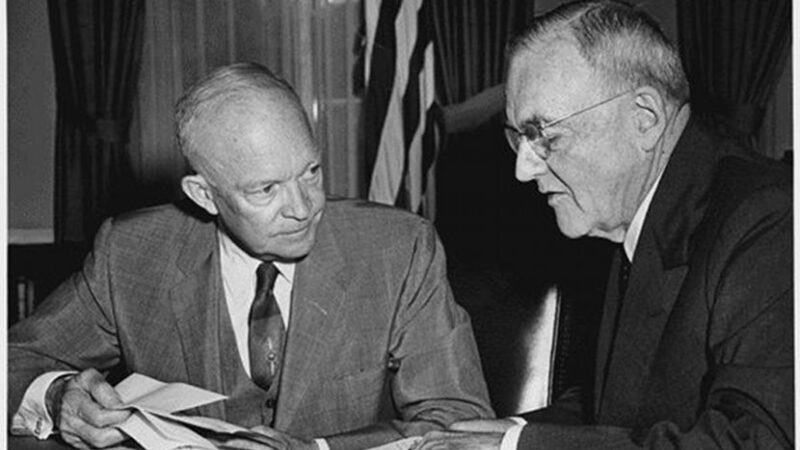

In 1953 Dwight Eisenhower gave his now famous “Chance for Peace” speech. It is worth repeating one key section of this speech in full:

“Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this: a modern brick school in more than 30 cities. It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population. It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals. It is some 50 miles of concrete highway. We pay for a single fighter plane with a half million bushels of wheat. We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people. This, I repeat, is the best way of life to be found on the road. the world has been taking. This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.“

Eisenhower is making two key points here. First, he is describing a world — one that came to pass — in which Americans would be poised for war at all times. This war, should it ever happen, had the potential to be an existential one because it would likely involve the use of nuclear weapons by both sides. That was the worst-case scenario. The best-case scenario, Eisenhower said, was:

a life of perpetual fear and tension; a burden of arms draining the wealth and the labor of all peoples; a wasting of strength that defies the American system or the Soviet system or any system to achieve true abundance and happiness for the peoples of this earth.

That “best-case scenario” still sounds pretty dark.

Eisenhower’s second key point here is about opportunity costs, the opportunity costs inherent to constructing and maintaining a military that consumes a significant amount of the country’s GDP each year. Here, we are really talking about the tradeoffs required in a world of vast but finite resources available to the United States. Clearly the United States has key interests — preserving itself as a nation, securing its territorial integrity, deterring attacks against the US homeland, preserving the lines of communication upon which its overseas trade (and national prosperity) relies — that must be protected by military capabilities. It will thus always have to have some kind of military, and given the size of the United States and its interests, it will want to have a preeminently powerful military.

But we must never allow ourselves to be persuaded that purchasing and maintaining such a preeminent military comes at no cost to ourselves or that spending our resources in this way does not squeeze out alternative things that we could purchase with those same resources. Eisenhower reminds us that military spending squeezes out other domestic concerns: social welfare programs, education, power and transportation infrastructure, and so forth. Creating such a military requires the efforts of some of the finest American minds (and bodies), who, rather than applying their talents to creating greater prosperity for themselves and other Americans, are consumed with building weapons of war.

Sadly, the relevance of Eisenhower’s points did not end with the Cold War but remain every bit as important today. To be fair, there was a small peace divided during the Clinton administration, when annual defense budgets fell from the FY1992 peak of $295 billion to a low of $263 billion in FY1994, and remained below the FY1992 level until FY2000, when the defense budget climbed to $304 billion. The defense budget climbed every year until FY2010, reaching a peak of $721 billion, then fell each year until FY2016, when it once more began to climb. As of March 2024, theUS Department of Defense FY2025 (FY2025) budget requestwas $850 billion. Whatever peace dividend existed following the collapse of the Soviet Union, it dried up within a few years before the September 11 responses and the “forever wars” in Afghanistan and Iraq, followed by current preparations for a new cold war with China, accelerated defense spending with no end in sight.

The United States has become a nation that remains perpetually ready to go to war. This was not the case prior to World War II. National military preparedness was sold to Americans beginning in 1940 with the nation’s first peacetime draft and the beginning of significant defense spending increases as a temporary measure needed because of global events and the predations of the Axis. That wartime expediency continued for the forty-five years of the Cold War. There was a brief respite in the 1990s and then September 11 ushered in a massive new wave of military expenditures. As the forever wars have wound down, calls to prepare against a new cold war with China have begun. The United States has lurched from one geopolitical crisis to the next since 1940 with no end in sight. While we never ended up with thegarrison state that Harold Lasswell feared in 1940, we have seen the rise of the military-industrial complex, the creation of the national security state, and a bloated military that is second to none, but with a price tag to match.

While a multitude of entrenched interests would oppose the notion of cutting military spending, cutting US military expenditures by 40-50 percent, as former Acting Secretary of Defense Christopher Millerhas called for, would not be as devastating as it might sound. This would return the United States to its pre-9/11 level of military spending, which is appropriate now that the Global War on Terror has ended. If coupled with defense acquisition reform, it would produce a US military that remains preeminent while also fostering innovation, investing wisely for the future, starving an insatiable military-industrial complex, and right-sizing the military so that it can secure core American interests. It would also provide room for federal tax reduction, deficit reduction, infrastructure investment, or any other use that would create value for American taxpayers. Perhaps most importantly, such a military spending decrease could provide a major bargaining chip — a kind of quid pro quo — for policymakers interested in concomitant domestic spending decreases.

Embarking on this path requires us to return to Eisenhower’s emphasis on the opportunity costs of out-of-control government spending. In Eisenhower’sFarewell Address, he once again addressed the theme:

As we peer into society’s future, we — you and I, and our government — must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering, for our own ease and convenience, the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without risking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage. We want democracy to survive for all generations to come, not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow.

For Eisenhower, fiscal prudence was a moral imperative.

- About the author: Andrew Byers is currently a non-resident fellow at the Texas A&M University’s Albritton Center for Grand Strategy. He is a former professor in the history department at Duke University and former director of foreign policy at the Charles Koch Foundation.

- Source: This article was published by AIER