By Cheng-Chwee Kuik

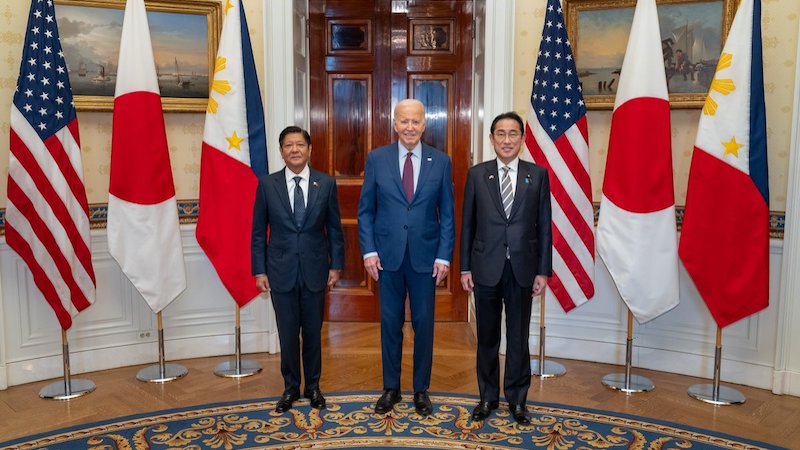

Proponents of the United States-led hub-and-spoke alliance system must have been excited by Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr’s visit to the White House on 11 April 2024 and the presidents’ historic trilateral summit with Japan’s Fumio Kishida the same day. It would seem that more spokes are being tied together, anchoring and advancing the hub beyond traditional bilateral links.

The Philippines is aligning itself more closely with Washington and Tokyo while expanding mutual engagement with Australia, Canada and Europe. Some commentators believe Manila is a bellwether for Southeast Asia, in particular claimant and littoral states of the South China Sea disputes, who will, sooner or later, follow in the Philippines’ footsteps and align fully with Washington and ‘likeminded’ partners to counter-balance Beijing.

This may well be wishful thinking. Under the current circumstances, the majority of Southeast Asian states are likely to;persist in hedging, rather than join with Washington and other Western powers against Beijing. Hedging is best understood as a pragmatic policy to;mitigate risks;and;maintain fallback options, rather than a fence-sitting or opportunistic act.

The conditions pushing the Philippines to return to the old alliance-first approach are not shared by other ASEAN states. An alliance-first or full-balancing policy is adopted when two conditions are present — the presence of a direct, clear and present threat and the availability of support from a reliable and robust ally. In the case of the Philippines under Marcos Jr, both conditions are clearly present and each is amplified by domestic political incentives, such as playing up the Chinese threat and privileging the US alliance to boost elite legitimation while undermining internal political foes.

Such conditions are not present for the other ASEAN states. Most Southeast Asian states do not consider China — at least not yet — a black-and-white threat, while the United States is not that straightforward a patron. Countries are like-minded;on some issues, but less so on others.

Another key reason is what I call the;’impossible trinity’. Like all sovereign actors, Southeast Asian states want to maximise security, prosperity and autonomy. But it is impossible for non-great powers to maximise all three goals simultaneously with a single policy and a single patron. Of the three goals that smaller states seek — freedom from security threats, from economic challenges and from autonomy erosion — only one, or at most two, can be attained through a single approach.

Take an alliance, or military alignment with mutual defence commitments. While this approach maximises security and often prosperity, the asymmetric nature of a defence pact inevitably presents the junior ally with risks of autonomy erosion and dependence.

Both risks have wider repercussions. The erosion of external autonomy leads to the erosion of internal authority, while a rigid alliance and dependence also expose the junior ally to the danger of alienating the opposing power. Then there is the danger of abandonment. Alliance is no panacea and there are trade-offs, drawbacks and downsides to all policy approaches.

Given the conditions the majority of ASEAN states face, these trade-offs are unacceptable. Unlike the Philippines and some of the United States’ ‘likeminded’ allies, the ASEAN states’ external outlooks remain in ‘shades of grey’. The weaker states continue to view both superpowers as sources of problems but also sources of support and solutions, albeit in different domains, to different degrees and for different reasons.

Accordingly, Southeast Asian states, except the Philippines, decline to embrace an alliance as the principal instrument of their external policies. While Vietnam and the older members of ASEAN, including Thailand, the other US treaty ally in Southeast Asia, have opted to partner with Western powers on defence and in other domains, they have also been cautious in ensuring that these arrangements are not about siding with one power against another. These ASEAN states have done so by forging partnerships in an inclusive but selective manner, forging closer partnerships in selective domains with different powers depending on their relative convergence of interests.

Indonesia, for instance, chooses to expand economic and strategic cooperation with China including through participation in Belt and Road Initiative projects, military exercises and high-level dialogues, while continuing to further develop its longstanding ties with the United States and other Western partners. Like other ASEAN states that have benefited from the accelerating China Plus One approach to investment, Indonesia has been cautious in offsetting the risks of being entrapped into any exclusive strategic bloc or supply chains by insisting on an open, inclusive diversification strategy.

Such a pattern of alignment choices may be more fragmented, less coherent and therefore less effective than a full-fledged alliance. But in the absence of a clear-cut threat, such an approach is more desirable because it allows states to maximise other goals like prosperity and autonomy while still keeping their security options open. Not putting all one’s eggs in the US-led alliance basket also enables regional states to hedge against the risk of abandonment, especially in the shadow of the possible return of former US president Donald Trump to the White House.

Hedging may not last forever and carries its own drawbacks. But hedging is at present;the most logical choice;for smaller powers in Southeast Asia and elsewhere seeking;to strike an acceptable balance;vis-à-vis the impossible trinity of security, prosperity and autonomy.

- About the author: Cheng-Chwee Kuik is Professor in International Relations at the National University of Malaysia and concurrently a non-resident scholar at Carnegie China.

- Source: This article was published at East Asia Forum