Learn more about sponsor message choices: podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Day: May 30, 2024

By Christopher M. Faulkne, Jaclyn Johnson, and Zachary Streicher

(FPRI) — Over the past decade, the Wagner Group made significant inroads across the African continent. Despite the death of its financier and figure-head, Yevgeny Prigozhin, the mercenary outfit has remained a fixture in Libya, Sudan, the Central African Republic (CAR), and Mali. Now under the auspices of the Russian state and the banner of the Africa Corps (or Expeditionary Corps), it has expanded its operations in Africa’s Sahel region, opening missions in Burkina Faso and now Niger. Yet, despite the Kremlin’s rebranding and takeover, Africa Corps and its broader missions appear quite similar to those of its predecessor. For client states, relying on Russian private military companies (PMCs) is a costly proposition—one which will fail to produce desired security and instead is likely to generate or exacerbate grievances within the security sector.

As a quasi-PMC, Wagner spearheaded security deals with dictators and military juntas for money and access to natural resources. In Libya, it fought alongside the forces of Khalifa Haftar and the Libyan National Army in hopes of acquiring access to Libya’s rich oil fields. In Sudan, it was contracted first by Omar al-Bashir to conduct disinformation operations and quash protestors in exchange for gold and act as a facilitator for Moscow’s ambitions to acquire a naval base at Port Sudan. In CAR it served as a praetorian guard for the Touadéra regime, as it gained access to lucrative mining operations and carved out its own economic projects from the timber trade to the alcohol industry. In Mali, it capitalized on anti-French sentiment, selling itself as the partner of choice for a nascent junta keen on breaking relations with Paris and in desperate need of counterterrorism support.

Following the death of Prigozhin in August of 2023, the Russian state engaged in a concerted effort to reel in the Wagner enterprise and fold the mercenary outfit into a new project under the command and control of the Russian Ministry of Defense, and specifically, the Main Intelligence Directorate. That project has had its own growing pains, but its expansion to Burkina Faso and Niger suggests progress. The latter mission has been billed as particularly worrisome for the United States, as the Russian outfit enters upon the drawdown of a decade-long American counterterrorism operation that saw the construction of a $100 million airbaseand was a key hub for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance across the region.

As these new missions suggest, Wagner, and its successor organization, offer the Kremlin far more than mere economic exploitation across a host of countries. They afford Moscow geopolitical access and influence on the relative cheap. Jockeying for influence across Africa, Russia’s private military enterprise promises clients enhanced security with “no strings attached” and permissive environments that favor authoritarian entrenchment. Mercenaries train armies and fight alongside them without lectures on human rights and the importance of civil-military relations—a value proposition attractive to young military regimes fatigued by partnerships with the West that were riddled with moral guardrails. In reality, however, Russian PMCs come with different strings attached and a host of unintended consequences.

Short-Term Consequences: Civilian Casualties and Exploitation

Wagner was a welcome feature by several African governments marred in severe and enduring security crises. In CAR, where civil war has been boiling for over a decade, Touadéra relied on Wagner to repel a rebel offensive around the 2020 election. In Mali, Wagner personnel have supported the Goïta regime, engaging in counterterrorism operations against swelling Islamist insurgencies and helping the Malian Armed Forces reclaim territory from Tuareg separatists in the country’s north.

On the surface, Wagner’s counterinsurgency and counterterrorism campaigns seem like success stories, at least to the buyers. Civilians in CAR acknowledge the brutality of Wagner’s tactics, but appear to welcomethe enhanced security, however fleeting. Wagner’s efforts to shore up Goïta’s security in Bamako, willingness to support the Malian Armed Forces’ campaigns against the Tuaregs, and subsequent territorial gains have won favor with some Malians. Yet, closer inspection reveals Wagner’s true modus operandi—one which completely, if not intentionally, ignores the law of armed conflict where its personnel target civilians, encourage and participate in rape and sexual violence, and overall, practices a policy rooted in indiscriminate targeting. That is far from a recipe for enduring security and instead exacerbates insecurity while setting the stage for military disgruntlement.

Wagner’s indiscriminate tactical choices are not only brutal but have been questioned in terms of their effectiveness. According to the Armed Conflict Location and Events Dataset, violence against civilians dramatically increased since Wagner entered the picture. This violence has included summary executions, even targeting children. In order to maintain plausible deniability, Wagner points to aggressive counterinsurgency campaigns that seek to promote stability as an explanation for civilian deaths. The vast amount of Russian propaganda and misinformation also work to preserve the reputation of Wagner. As one analyst noted, Russian PMCs have decided that action, even at the risk of mistakes, is more valuable than inaction. While it is worth noting that the trajectory of violence in both Mali and CAR was trending in a dismal direction before Wagner’s involvement, Wagner only accelerated those trends, and the Africa Corps will undoubtedly carry the baton.

Beyond the steep consequences of Wagner’s tactical choices in the security realm, the organization leverages its access in the region to extract resources in a brazen display of neocolonial tendencies. Wagner’s business proposition promulgates regime security for access to resources. Fledgling regimes benefit from the enhanced security, or the promise of it, while the Wagner network of shell corporations gain a stake in the extractive industries of client states. In CAR, Wagner subsidiaries like Lobaye Invest and Midas Resources are key players in the gold and diamond industry, helping cover Wagner’s bill, enrich Russian oligarchs, and aid the Kremlin’s sanctions-busting regime. Though less successful in Mali, Wagner tried to inject itself into Mali’s gold mining sector. That trend has continued, with Bamako and Moscow signing an agreement late last year that would lead to the construction of Mali’s largest gold refinery. The predatory nature of this resource extraction can benefit the Kremlin’s war-fighting efforts elsewhere.

Potential Long-Term Costs of Contracting Russian PMCs: Intra-Military Dynamics

While the immediate effects of Wagner are fairly observable, the seismic shifts impacting militaries in the region have gone largely under-explored by observers and scholars. Our ongoing research examines the potential implications for state forces when leaders pursue a policy of contracting PMCs. Several recent anecdotes point towards fracture, disruption, and low morale among state militaries as a direct result of Wagner’s operations in the region. Despite marketing itself as a better partner than the West, Russian PMCs are setting the stage for enduring intra-military conflict.

To date, research on outsourcing to PMCs has largely focused on the downstream effects of contracting, with most studies focused on how partnerships with these particular actors influence conflict dynamics like intensity, duration, and recurrence. Yet, the injection of PMCs can also influence the military in unique ways. Wagner’s arrival in places like CAR and Mali, for instance, was packaged as a godsend for militaries facing extensive security challenges. However, outsourcing security, especially when that decision is associated with significant investment devoted to outside agents, has the very real potential of generating significant grievances amongst rank-and-file soldiers. These grievances may be particularly likely to take root in places that face severe resource constraints or unfavorable conditions for soldiers. This unique confluence of conditions—limited material resources and unfavorable, dangerous conditions for personnel countering multi-pronged insurgencies—currently defines the Sahelian landscape, making these militaries especially susceptible to rebellion and fractures. Such risks are only amplified with the introduction and continued presence of PMCs.

Put simply, reliance on PMCs like Wagner can aggravate the armed forces just as much as it can aid them. Besides the obvious cost-related grievances where a government’s decision to spend on PMCs may divert resources away from the military, a country that deems it necessary to contract a PMC can degrade morale. Whether there is an actual need to seek outside assistance, or the perception of it, some members of the armed forces may see such contracting as a vote of no confidence and, in accordance, act out in ways that overtly signal their discontent. In short, they may mutiny.

Mutinies are military protests intended to send a sharp signal about collective grievances. Mutinies are often an early indicator of military discontent that if left unchecked can erupt into more dramatic events like coups or mass defections. Wagner’s operations in CAR appear to have generated some rifts across segments of the security sector. Reports from humanitarian watch dogs suggest that friction between the gendarmerie in CAR and Wagner, a byproduct of Wagner’s indiscriminate tactics, led the military police to mutiny in a show of discontent. The event brings into focus the ways in which Wagner’s tactical choices are undermining institutions in the region.

Additionally, dissatisfaction with and/or suspicion of Russian PMCs may lead some soldiers to defect and/or desert. In CAR, anecdotal evidence points to Central African Armed Forces experiencing such defections, reportedly as a direct consequence of Wagner. According to reports, former rebels that had been drafted into the army by Wagner defected to (re)-join the main opposition rebel group, the Coalition of Patriots for Change. Their motivation stemmed, in part, from rumors that Wagner was training and reallocating soldiers to other fronts in Mali and Ukraine. In an interview, one of these defecting soldiers stated, “Our colleagues who disappeared are not in Bangui nor in Berengo, whereas we were told they had been moved to the capital for further training. Perhaps they are right now in Ukraine to serve as human fodder to the Russian forces.”

These intra-military dynamics are a symptom of a much larger problem, one that could be exacerbated by the presence of Russian PMCs. Outside of CAR, there is potentially a profound impact on state security should the militaries of a growing list of Russian PMC clients in the Sahel experience desertions, defections, low morale, and mutiny. A state is only as strong as its military is resolute. The very thing that Wagner/Africa Corps was contracted to supply—security—is the very thing that it may jeopardize.

Outside of tactical choices leading to aggrieved soldiers, intraorganizational friction, may also ensue when a state contracts a PMC whose personnel then assume positions of authority over the rank-and-file. Subservience to outsiders can generate grievances that threaten organizational cohesion, and with it, military effectiveness. The ongoing case of Wagner/Africa Corps in Mali is illustrative of this dynamic, as researchers note that despite shared attitudes on counterinsurgency strategies, some members of the Malian armed forces are growing disgruntled with Russian mercenaries. Issues with command and control, lines of authority, and even racism have each been cited as key features leading to disgruntlement. Though perhaps too early to tell, the reported friction may ultimately lead to buyer’s remorse, and with it, military revolts.

While information is sparse, the reality is that Russian PMCs are sowing the seeds for client’s future civil-military challenges. As the above cases illustrate, there is real (and growing) potential for Wagner’s tactical and operational choices, along with the cost of their contracts, to threaten intra-military cohesion. And with the Africa Corps expanding to more Sahelian states with recent histories of fragile civil-military relations, the risks are even more likely. Contracting Wagner may have solved a short-term security challenge for new juntas, but that solution has the potential to create serious and lasting internal challenges that will manifest as military mutinies at best and more serious civil-military crises at worst. While such friction may be limited to date (or at least limited in terms of what is publicly known), it is worth paying attention as relationships between Africa Corps and state militaries evolve. As the expression goes, familiarity breeds contempt.

An irony here is that in cases such as CAR and Mali, Wagner was/is as much a “coup-proofing” remedy as it was a counterinsurgency force. As scholars have shown, foreign recruits can have a dampening effect on the likelihood of coups, creating significant barriers to coordinating a putsch. But while relying on PMCs like Wagner may insulate regime leaders from the most serious threats to their reign, such partnerships lay the foundation for security sector frictions that come with a whole different set of problems.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

This analysis is not the first to consider the many ways that Wagner is more adept at providing regime security than human security in the face of insurgent threats. Indeed, others have argued that Wagner could be aggravating insurgency across the region. Instead, this analysis explores a new pathway through which grievances are likely to manifest moving forward, specifically through Wagner jeopardizing the institutional interests of the state’s military.

Wagner’s effect on African militaries is an important element of the Kremlin’s broader global influence. The West and International Organizations like the United Nations, Economic Community of West African States, and the African Union have sought to develop anti-coup norms that curtail military takeovers. Norms are foundational understandings that guide behavior in important ways, and in this instance, in a way that reinforces democracy. The anti-coup norm has already been jeopardized by Wagner’s direct, tacit support of coup-born leaders. That anti-coup norm could be tested even more as Sahelian militaries grapple with the aggravations of integrating with Wagner and accommodating the organization’s costly tactical choices. As these norms deteriorate further, the international community may have only observed the first step in a larger crescendo of destabilization.

Despite limited evidence to date of Wagner/Africa Corps fueling intra-military friction, it isn’t hard to imagine a reality in the not-so-distant future where client state militaries become increasingly disgruntled with their Russian security partners, or with other segments of the armed forces who may be more closely aligned with or supported by Russian PMCs. Though far from analogous, one needs to look no farther than the Wagner mutiny in June 2023 to see that the recent track record of Russia’s Ministry of Defense is one where intra-military and paramilitary disputes have created serious challenges.

Our understanding of the effects of Wagner’s operations in central Africa and the Sahel is virtually developing in real-time. Because of this—and given the evolving nature of the organization and the maturation of its activities in the region—it will be critical to closely monitor the interactions between Africa Corps and rank-and-file soldiers. Doing so will not only be prudent for countering Russian PMCs and their narrative that they are better partners, but can also be instructive for any future security force assistance.

About the authors:

- Christopher M. Faulkner is an assistant professor at the US Naval War College. He researches and writes on issues related to irregular warfare, militant financing and tactics, private military and security companies (PMSCs), maritime terrorism, and civil-military relations. The views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the US Naval War College, Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or US Government.

- Jaclyn Johnson is a Lecturer at the University of Kentucky. Her research focuses on civil-military relations with specific attention on military mutinies. She developed the first quantitative, global sample of mutinies and her research has been published in the Journal of Peace Research and the Journal of Conflict Resolution.

- Zachary Streicher graduated from the University of Kentucky in Spring 2024 with a B.A. in Political Science. He has conducted research on the influence of private military contractors on civil-military relations. His primary research area centers on the post-Soviet world and he also studies the Russian language.

Source: This article was published by FPRI

By Harsh V. Pant and Vivek Mishra

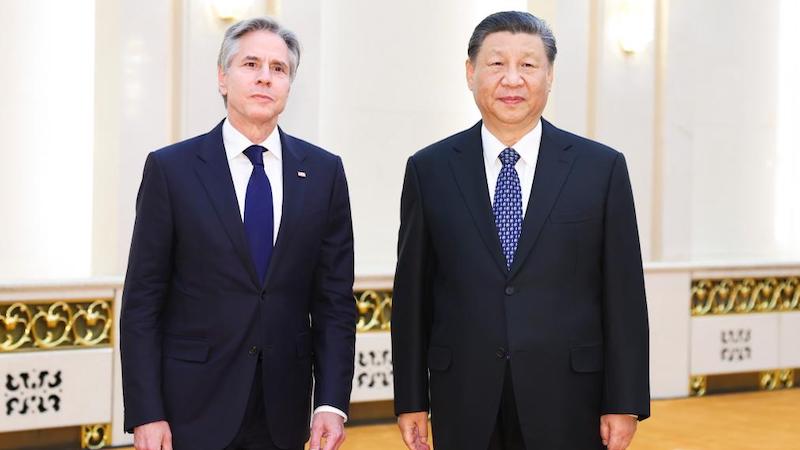

When the United States (US) secretary of state, Antony Blinken, travelled to China last month, his purpose was threefold: First, to assess the concrete steps taken in the bilateral relationship since Presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping met in San Francisco in November 2023; second, to reposition the focal point of US-China relations within a rapidly shifting international landscape; and finally, to “de-risk” the bilateral relationship by ensuring that China maintains a favourable disposition towards Washington. To achieve that, Washington’s approach has been a combination of incentives and deterrents.

During the visit, lines were once again drawn between the two sides, highlighting simmering disputes on issues such as trade, technology, and security. There is a keenness in Washington to prevent these cracks from widening further, particularly in light of the repercussions of ongoing conflicts in Europe and West Asia. Of particular concern is the burgeoning China-Russia relationship, with the US expressing worry that China may be providing vital technologies to the Russian defence industry, thereby bolstering the latter’s capability to maintain battlefield advantages and undoing western support.

The Biden administration has consistently signalled a stance of cooperation alongside measures that have fuelled competition. On May 14, the US increased tariffs across strategic sectors such as steel and aluminium, semiconductors, electric vehicles, batteries, critical minerals, solar cells, ship-to-shore cranes, and medical products to curb China’s unfair trade practices in key sectors like tech transfer, innovation and intellectual property.

Since the Anchorage summit in March 2021, when the bilateral relationship seemed to veer off course, the focus has been on “responsibly managing competition” from the US. Incidents such as former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022 and the spy balloon incident in January 2023 have redrawn the boundaries of the US’s competitive approach towards China. Meanwhile, the Biden administration has initiated a tech competition with China since the passage of the 2022 CHIPS and Sciences Act, prompting retaliatory measures from China.

The impact of these disruptions has been further compounded by instability in the world order. The past couple of years have been immensely destabilising for the international system, marked by the wars in Europe and West Asia and the systemic shocks arising from them. The US-China relationship has not been immune to these impacts.

Blame it on the age of globalisation and interconnectedness, but the US-China relationship is, in many ways, a uniquely significant great power dynamic. It stands out, particularly in how it has evolved distinctively from the competitive relationship between the US and the Soviet Union during the last century. Today, between its relations with China and Russia, it is primarily with China that the US can attempt moderation. Simultaneously, China remains deeply integrated with western economies. These mutual dependencies have prevented a complete rupture in bilateral relations. Two successive high-profile visits within a month — Janet Yellen and Antony Blinken — suggest that Washington is intent on maintaining engagement with Beijing amidst the shifting sands in Ukraine and the blitz in Gaza.

Several cooperative steps between the two countries, such as joint efforts to combat synthetic drugs like fentanyl through the establishment of a joint Counternarcotics Working Group, collaboration on policymaking and law enforcement in this regard, and the resumption of military-to-military talks at various levels, along with the agreement to hold US-PRC talks on Artificial Intelligence in the coming weeks, underscore the shared compulsion to avert any regional or global crisis that might escalate into military conflict between the two powers.

However, China perceives an opportune moment to assert itself distinctly against the US as the sole alternative power centre with comparable capacities, global heft, and influence to engage wayward countries beyond Washington’s control, such as Russia, Iran, North Korea, and Syria. Recent US intelligence suggesting potential collusion between Russia and China on the issue of Taiwan has prompted preparations for a new form of joint military readiness from the US and its regional allies.

Blinken’s visit may be another way of signalling to China that it shouldn’t exploit any crisis to escalate new ones, at least until the US elections are over in November of this year.

About the authors:

- Professor Harsh V. Pant is Vice President – Studies and Foreign Policy at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.

- Vivek Mishra is a Fellow with ORF’s Strategic Studies Programme. His research interests include America in the Indian Ocean and Indo-Pacific and Asia-Pacific regions.

Source: This article was published by Observer Research Foundation and originally appeared in Hindustan Times.

It is not yet clear whether Hungary is just an unwilling ally or rather a Trojan horse that is already preparing to switch sides.

By Istvan Szent Ivanyi

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Europe’s enfant terrible, is a master of making unexpected and surprising statements.

His latest came during his weekly Friday radio interview, in which he stated that Hungary is now both in and out of NATO, or “non-participant”. Although he explained this is not yet a true “opt-out”, Hungarian diplomats and military leaders, he said, have been looking for some time into the possibility of Hungary remaining a member of NATO without participating in operations outside of its mandated area.

During the interview, Orban restated his well-known and unequivocal position on the Russia-Ukraine war. It is a war between two Slavic peoples that the West has nothing to do with; NATO’s task should be to isolate the war and not to escalate it; and Hungary does not wish to participate in the war at any level, neither militarily, logistically nor financially.

Orban did not reveal any further details about this Hungarian “opt out” that is apparently in the works, though many experts believe his statement should not be given too much weight because there is no real intention or content behind it. Partly it was a bluff, partly a war-and-peace theme framed by Orban’s Fidesz party for the election campaign currently underway for the European Parliament.

Communicated via all possible media channels, Fidesz claims that those who want peace should vote for Fidesz, because the opposition and, of course, Western leaders are driving Europe and Hungary into war. Only Fidesz and the prime minister can protect the Hungarian people from the horrors of a Third World War. Recently, Hungarians have been threatened with the nightmare of a nuclear war, from which only Orban can protect them. It is not in dispute that Orban always subordinates everything to domestic politics and within that to his own hold on power, so we cannot rule out this explanation.

Yet at the same time, the “opt-out” statement comes amid a wider context, which could lead us to draw more worrying conclusions about whether Hungary is just an unwilling ally or actually preparing to switch sides.

Mind your language

The Hungarian government’s relationship with NATO has long been conflictual, constrained and ambivalent.

For many years, practically since the beginning of Russian aggression in Ukraine in 2014, the Hungarian government has blocked Ukraine’s rapprochement and high-level cooperation with NATO.

The ostensible reason for this was the Ukrainian education and language law passed in 2017, which undoubtedly restricted the use of minority languages in certain circumstances. This legislation was primarily aimed at limiting the rights of the Russian minority, but they undoubtedly adversely affected and discriminated against Ukraine’s Hungarian, Polish, Romanian and other ethnic minority populations as well.

The Hungarian government took a different position than either the Polish or Romanian governments on this issue; while the latter two sought a separate agreement with the Ukrainian state, Hungary demanded the repeal of the law in its entirety, which gave the impression that it was representing not only its own interests but also those of Russia in the matter.

Further reasons for forming this impression are not hard to find. Although Orban eventually participated in all 13 of the EU’s sanctions packages against Russia, he did so reluctantly, stalling for time, extorting concessions, and threatening to use his veto. Perhaps the most infamous was the case of Patriarch Kirill, Moscow’s war-mongering bishop, who was removed from the sanctions list following a Hungarian veto.

Since 2018, the dubious development bank with Russian majority ownership, the International Investment Bank (which everyone dubbed a “spy bank”), operated freely out of Budapest. The Hungarian government only cancelled the headquarters agreement when the US threatened severe sanctions and the bank’s finances were crumbling.

There is no doubt that at the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Hungary was highly dependent on Russian energy supplies. Common sense would have demanded that the government ease this dependency and diversify Hungary’s energy imports. Yet just the opposite has occurred. After the start of the war, the agreement on accelerating the construction of the Paks 2 nuclear power plant was signed with Russia’s Rosatom, which will only increase and prolong Hungary’s vulnerability to and dependency on Russia. Although the technical conditions exist and are right for oil and gas import diversification since Hungary is connected to six of its neighbours through interconnectors, no meaningful steps have been taken to diversify energy supplies.

The public service and pro-government media also largely cleave to the Kremlin’s narrative over the war in Ukraine. This clearly has had a major impact on public opinion. While at the outset of the invasion, the Hungarian public was clearly critical of President Vladimir Putin and Russia, today the situation has not only moved in the Russian president’s favour, but a significant portion of the pro-government audience has become anti-Ukrainian and takes an understanding attitude towards Russia’s war of conquest.

This attitude is personified by Peter Szijjarto, the Hungarian foreign minister. Less than two months before the aggression, Szijjarto received the highest Russian state award, the Druzhba (Friendship), from his Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov. Szijjarto has since refused to return this award and still refers to Lavrov as his “good friend”. Since the beginning of the war, he has visited Russia seven times, met Foreign Minister Lavrov six times, and has also visited Belarus, Russia’s nominal ally in its war with Ukraine.

Orban has also visited Russia since the war began, although it was to attend Mikhail Gorbachev’s funeral in September 2022 and, according to reports, he did not meet President Putin. But Orban made up for that a month or so later when he was in Beijing for an international forum marking the 10th anniversary of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Incidentally, three weeks before Russia’s invasion in February 2022, Orban visited Moscow, where he had a five-hour intimate exchange of views with Putin.

At the same time, neither Orban nor Szijjarto have visited Kyiv since the beginning of the war. Negotiations are currently underway to improve relations between the two countries, but they are progressing at a snail’s pace. In a recent telephone conversation, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky invited Orban to the June peace summit in Switzerland, yet so far it is not clear whether and at what level the Hungarian leadership will attend. Most experts rule out Orban’s personal participation in the talks; if there is Hungarian participation at all, most probably it will not be at the highest level.

Much of this might be construed as Hungary hedging its bets over the war in Ukraine and trying to balance its national interests. But there are more worrying examples of Hungarian collusion with the Kremlin on a deeper level.

Hacked or handed?

Documents relating to a previously reported spying case at Szijjarto’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade – vigorously denied by the government at the time – have recently surfaced.

Two years ago, it was leaked to the press that a serious national security breach had taken place at the Foreign Ministry when hackers from the Russian military and civilian intelligence services (GRU and FSB) penetrated the IT system of the ministry, allowing them unrestricted access to harvest valuable, secret information. A total of 4,000 computers and 930 servers were reportedly compromised.

When confronted by the independent media with the story in March 2022, the foreign minister and other government officials denied everything, calling the story a campaign lie coming as it did just before the April general election of that year. However, official documents have now emerged that clearly confirm the fact and scale of the intrusion – and the government knew all about it.

The government is now in a tricky situation: no longer able to deny it, its officials now try to trivialise and belittle it. They claim there are hacking attempts every day and from all directions, and they won’t talk about it for reasons of national security. It is striking how far they will go to protect Hungarian-Russian relations based on what they call “mutual respect and trust”.

According to Daniel Hegedus, a foreign policy analyst at the German Marshall Fund, this was no accidental intrusion, but a conscious transfer of information on behalf of the Hungarian authorities to the Russian side. Of course, this cannot be proven, but given the context, it seems plausible. Likewise, although I have not seen any clear evidence, report or document substantiating it, intelligence sharing between Hungary and its Western allies is understood to be marked by a reluctance to share confidential information.

The government’s ambivalence regarding NATO membership is well illustrated by the fact that the 75th anniversary of the founding of NATO and the 25th anniversary of Hungary’s NATO membership were not accompanied by any state celebrations or events, unlike in other fellow Visegrad Group countries – Czechia and Poland – that joined the alliance in the same year. Only civil society events and academic events reminded us of these important anniversaries.

In view of all of this, we can no longer be sure that when Orban talked in his radio interview about a possible unilateral path, a Hungarian opt-out within NATO, he was not being serious about signalling the beginning of an attempt to distance his country from the defensive alliance or even leave it altogether.

Unfortunately, it is not yet clear whether Hungary is just an unwilling ally or rather a Trojan horse that is already preparing to switch sides. Neither of these options can be ruled out.

- About the author: Amb. Dr István Szent-Iványi is a foreign policy analyst and expert, serving as Senior Fellow of Department, International Relations and European Studies at Kodolányi János University in Budapest, and Vice Chair of the Hungarian Atlantic Council.

- Source: The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN.