Day: May 23, 2024

(RFE/RL) — The investigative group Conflict Intelligence Team (CIT) confirmed on May 23 that a Ukrainian missile attack four days earlier on the port of Sevastopol hit a Cyclone missile carrier ship belonging to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.

CIT said that, after reviewing photographs of a sunken ship showing a mast sticking out of the water, it concluded that the vessel was the Cyclone missile carrier. The Karakurt-class corvette joined the fleet six months earlier.

Russia has not confirmed the loss of the vessel and no information has been made public about possible casualties among the ship’s crew.

British intelligence said that the Russian ship was “almost certainly” sunk by a Ukrainian strike on Sevastopol in occupied Crimea on May 19.

The attack likely involved a combination of drones and ATACMS missiles, British intelligence said. The Cyclone missile carrier was one of four Russian vessels of the Karakurt class. It was armed with Kalibr cruise missiles, which have been used against Ukraine.

Two of the Karakurt-class vessels were likely diverted to the Caspian Sea to safely complete sea trials following a series of successful Ukrainian attacks, British intelligence said. The fourth vessel was previously seriously damaged in a Ukrainian strike in November 2023.

British intelligence noted that, while it is unlikely to significantly change the impact the Russian Navy is having on Ukrainian operations, the strike “does highlight a continued danger to Russian forces operating in the Crimea and the Black Sea region and continued Ukrainian success when conducting coordinated strikes.”

The CIT also referred to a minesweeper called the Kovrovets, which it said was not visible in the port as of May 21. The Ukrainian military reported on May 19 that the ship was destroyed in its attack on Sevastopol. The Ukrainian Navy did not give additional details.

According to the General Staff of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, Russia has lost 26 ships and boats and one submarine since it launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Moscow does not comment on the losses.

The Ukrainian Navy claims that Russia almost never sends its ships to the Black Sea in light of the damage and destruction that Ukrainian forces have inflicted.

For more than two decades, jihadists took pride in place as symbols of extremism and illustrations of the need for religious reform. They made Islam the focus of post-9/11 calls for religious change and moderation.

Today, Islam no longer stands alone. One of the world’s foremost faiths, Islam has been joined by most major religions that have long flown under the radar.

Numerous recent examples and incidents in an increasingly polarised world that allows religion to become a clarion call for supremacy, racism, bigotry, and prejudice highlight the urgency of expanding the post-9/11 clamour for ‘moderate’ Islam to other major faiths, including Christianity, Judaism, and Hinduism.

Extremist rabbis, ultranationalist and ultraconservative Israeli politicians, far-right Evangelicals, Russian Orthodox Church leaders, and Hindu nationalists have emerged as equally troublesome militant, supremacist, and racist expressions of faith.

Together, they demonstrate that problematic tenets and practices of religion pose a universal threat that transcends Islam.

Failure to reform religious jurisprudence and norms allows religious militants, irrespective of faith, to justify their militancy, supremacy, and violence in theology and religious law.

Countering those expressions in an increasingly polarised, us-or-them world, in which religious militants’ impact or control the levers of power in countries like Israel, Iran, and India or wield significant behind-the-scenes influence as in Russia, is no mean fete.

For much of the past decade, Indonesia’s Nahdlatul Ulama, the world’s largest and most moderate Muslim civil society movement, has led the clarion call for religious reform, albeit with mixed results.

Even so, Nahdlatul Ulama, a conservative center-right movement, deserves credit for leading by example, persistence, determination, and willingness to go where others have not dared to tread or did not have the clout to do so.

A mass movement with 90 million followers, a five-million-strong militia, thousands of religious seminaries, hundreds of universities, and a religious authority of its own, Nahdlatul Ulama is in a class of its own.

Islamic history boasts numerous forward-looking reformists. However, in contrast to Nahdlatul Ulama, they were primarily intellectuals and clerics, some with significant followings, yet none with the infrastructural and organizational backbone needed to boost their quest.

In recent years, Nahdlatul Ulama’s religious scholars acted on the movement’s call for reform of “obsolete” or “outdated” provisions of Islamic jurisprudence with fatwas or religious opinions that replaced the notion of a kafir or infidel with that of a citizen and called for the elimination of the concept of a caliphate in favour of the nation-state.

The problem is that fatwas are not binding. While most Nahdlatul Ulama followers may abide by the opinions, other Indonesian Muslims may not.

Similarly, Nahdlatul Ulama has set an example for the Muslim world. However, the fatwas have yet to be emulated elsewhere.

If anything, major status quo Muslim institutions, including Al Azhar, the more than 1,000-year-old, Cairo-based citadel of Islamic learning, Saudi Arabia’s government-controlled Muslim World League, and United Arab Emirates-sponsored religious groups have sought to co-opt the Indonesian movement.

To its credit, Nahdlatul Ulama has stood its ground, insisting on religious reform that includes religious and political pluralism.

In doing so, Nahdlatul Ulama challenges its major Muslim rivals’ view of moderation which emphasises religious tolerance and interfaith relations, while upholding the autocratic principle of absolute obedience to the ruler.

Arab rulers have used their concept of ‘moderate’ Islam to legitimize their iron fist rule and crack down on dissent religiously. Saudi Arabia has gone as far as defining atheism as terrorism and has yet to allow non-Muslim houses of worship to operate legally.

Autocrats have exploited their definition of ‘moderation’ to project an image of forward-looking societies that attract needed foreign investment and reap the economic, social, and political benefits of religious and social tolerance.

“Harnessing the benefits of religion – including the considerable economic gains available – requires taming of the tendency for followers of one religion to exclude and work against non-followers,’ said Bahraini analyst Omar Al-Ubaydli.

Religious tolerance and interfaith dialogue constitute a step forward.

Even so, the Gaza war, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Evangelical support for Israel, rising anti-Semitism, Russia’s Orthodox Church-backed invasion of Ukraine, and anti-Muslim Hindu nationalist agitation suggest that religious tolerance and interfaith dialogue do not suffice.

To structurally address a problem that feeds discrimination, racism, and polarisation, religious tolerance and interfaith dialogue need to be embedded in reforms that counter bigoted, supremacist, and prejudiced expressions of faith and promote religious, social, and political pluralism and diversity.

The consequences of failure to do so are omnipresent. They dominate newscasts and online and social media with reporting from flashpoints like Ukraine and Gaza and on the rise of the far right in Europe and the United States, as well as the curbing of freedom of expression in the West when it comes to supporting the Palestinians.

As a result, Nahdlatul Ulama’s call for reform is not just valid for Islam and Muslim autocracies. It applies equally to illiberal democracies that cloak themselves in religious nationalism like Hungary and India, authoritarian regimes like Russia, and partial democracies like Israel that uphold democratic principles for Jews but limit Palestinian rights.

The urgency of religious reform is spotlighted by leaders like Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, who heads the most ultra-conservative and ultra-nationalist government in Israel’s history and projects himself as the protector and spokesperson of world Jewry but has no compunction about aligning himself with Jewish supremacists who view their Jewish critics as traitors and non-Jewish figures who flaunt their association with anti-Semitism.

Men like Mr. Netanyahu’s Diaspora Affairs and Struggle Against Anti-Semitism minister, Amichai Chikli, find common ground with often anti-Semitic ultra-conservatives and far-right politicians in their opposition to ‘radical Islam’ which translates into support for Israel’s effort to destroy Hamas.

Earlier this month, Mr. Chikli spoke at a gathering of European far-right activists hosted by Vox, Spain’s ultra-right political party that Israel once shunned for welcoming neo-Nazis and Holocaust deniers into its ranks, including Pedro Varela, an infamous Barcelona Nazi bookseller, who spent time in jail for disseminating hate speech and nominated Holocaust denier Fernando Paz as a congressional candidate in Spain’s 2019 election.

Several other Netanyahu associates, including parliamentarians Amit Halevi and Simcha Rothman, the architect of the prime minister’s controversial judicial reform, and Science and Technology Minister Gila Gamliel, spoke earlier this year at influential Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) meetings in Maryland and Hungary alongside Holocaust deniers, self-identified Nazis, and Christian nationalists.

Speaking in Maryland, far-right conspiracy theorist Jack Posobiec greeted participants on the first day of the gathering, saying, “Welcome to the end of democracy. We are here to overthrow it completely…and replace it with this because all glory is not to government, all glory to God” as he held up what appeared to be a cross on a chain.

Earlier this month, Knesset speaker Amir Ohana, a member of Mr. Netanyahu’s Likud Party, invited reformed New York Republican Congresswoman Elise Stefanic on a blitz visit to Israel.

Ms. Stefanik profiled herself as a staunch opponent of anti-Semitism in the recent Congressional grilling of university presidents and a supporter of Israel.

Mr. Ohana overlooked Ms. Stefanic’s failure to account for her history of anti-Semitism, including her propagation as recently as two years ago of the white supremacist Great Replacement Theory. The theory asserts that America’s elite, at times manipulated by Jews, aims to replace and disempower white Americans. The theory sparked mass shootings in the United States.

A white man with a history of antisemitic internet posts in 2018 gunned down 11 people in a Pittsburgh synagogue.

A year later, another white man, angry over what he called “the Hispanic invasion of Texas,” opened fire on shoppers at an El Paso Walmart, leaving 23 people dead.

And in yet another deadly mass shooting in 2022 in Buffalo, New York, a heavily armed white man killed ten people in a supermarket on the city’s predominantly Black east side.

“The State of Israel and the Zionist movement has actually sought the support of well-known anti-Semites as long as they are politically in their corner… People who are bigoted, anti-Semitic, who hate Jews but are willing to support the State of Israel, are welcomed by Netanyahu and his ilk,” said Jonathan Kuttab, an international human rights lawyer, board member of the Bethlehem Bible College, and president of the Holy Land Trust.

When Mr. Kuttab recently asked the pastor of an Evangelical megachurch to pray for the children of Gaza, the cleric refused.

“I don’t want to create trouble because I believe in the Prophecy. All these Jews are going to gather (in Israel),” Mr. Kuttab quoted the cleric as saying, adding that “then, with a big smirk on his face, he said, ‘they’re all going to die because (of) Armageddon, they’re all going to be destroyed except those who accept Jesus Christ as the Saviour.’”

Mr. Netanyahu, who has denounced pro-Palestinian protesters as “anti-Semitic mobs.” shrouded himself in silence earlier this month as Christian prayer leader and singer Sean Feucht led his far-right followers in a pro-Israel march against pro-Palestinian demonstrators at a University of South California (USC) campus to portray the Gaza war as a harbinger of the ‘End Times’ predicted in the Bible.

Mr Feucht was joined at the campus by Ché Ahn, the leader of Pasadena’s Harvest Rock Church, who defines being pro-Israel as converting Jews to his brand of Evangelical Christianity.

Dressed in a Jesus rocker-style black jean jacket, Mr. Feucht told Fox News, “We want Americans to see that we are fed up with this rot of anti-Semitism on the college campuses.”

Fox News passed on the opportunity to question Mr. Feucht on his association with the far-right Proud Boys, QAnon conspiracy theorists, the ReAwaken America Tour, a conspiracy-laden road show, and Elijah Schaffer, a podcaster, all notorious for their anti-Semitic tendencies.

“I do interfaith dialogue for a living. These people are not doing interfaith dialogue. They’re doing Christian supremacy, but they’re cloaking it in the garb of interfaith solidarity,” said Matthew D. Taylor, a religious studies scholar and expert in Christian nationalism.

A retired historian warned in an email, “If the chain of apocalyptic events that the Christian Zionist expounders of bogus ‘Bible prophecy’ have conditioned millions of American Christians to believe that they are preordained by God, including catastrophic war and a second Holocaust with the Palestinians as its victims, is brought about and then Jesus does not return when their ‘prophecy’ predicts – and he will not – Christianity will become abhorrent in the eyes of the world, seen by non-Christians as a genocidal doomsday cult. And it will spark a global firestorm of anti-Semitism against all Jews.”

In the spirit of Nahdlatul Ulama, Mr. Kuttab, the Palestinian lawyer, advocates engagement with Evangelical Christians and believes that effecting change is possible. Mr. Kuttab’s view implies that Evangelicals, unlike ultra-nationalist and ultra-conservative Jews, Hindu nationalists, and militant Islamists, may be low-hanging fruit, at least when it comes to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“The appeal for Christian Zionism is very broad, but it’s very thin… It’s not as fundamental to their identity as issues like abortion, for example, or homosexuality. For them, support for Israel is like a default position that they haven’t thought much about because they were never asked or questioned or challenged on it… They equate the Israel of the Bible with the modern state of Israel… They sort of jump over 2,000 years of history, and they jump over most of the New Testament,” Mr Kuttab said.

“So, when you sit with them and quote the Bible to them, they are very liable to change their positions, but you have to talk to them in Biblical terms. You have to quote scripture to them… You have to talk to them about Christ love, Christ compassion, Christ being the Prince of Peace, Christ being open to everybody, to salvation for God loves the world, not just the Jewish tribe, that he gave his only begotten son. So, whoever believes in Him shall not perish but have everlasting life. When you talk to many Christian Zionists in that language, they say,’ Hmm, we never thought about that. Maybe you are right.’… The problem is that most people who talk to Christian Zionists don’t use that language,” Mr. Kuttab added.

Earlier this month, the United Methodist Church, a mainstream Protestant church with some 5.4 million followers and 30,000 houses of worship in the United States that has lost up to a quarter of its membership because of its increasing tolerance of same-sex marriage, called on its investment managers to divest from Israeli bonds as well as Turkish and Moroccan securities.

The church cited as reasons for the disinvestment Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories conquered during the 1967 Middle East war, the continued presence in Northern Cyprus of Turkish troops since Turkey invaded the Mediterranean island in 1974, and the Moroccan occupation of the Western Sahara since 1975.

The rise of Israel’s far-right government shines a spotlight on problematic elements of Jewish law reflected in Israel’s Gaza war conduct, its us-or-them approach to Palestinians, and its policies on the West Bank.

Early in the war, Mr. Netanyahu invoked the Biblical command to “attack the Amalekites” and destroy all that belongs to them. “Do not spare them; put to death men and women, children and infants, cattle and sheep, camels and donkeys,” the command says.

Although challenged by numerous rabbinical scholars over the centuries, Israeli politicians and military personnel fighting in Gaza echoed Mr. Netanyahu’s invocation.

Ultraconservatives view Amalek, the grandson of Esau and his descendants and anyone else who lived in their Canaanite territory, as the archetype of evil symbolic of Israel and the Jews’ nemeses.

Earlier this month, far-right Rabbi Dov Lior, a proponent of killing and ethically cleansing Palestinians, legitimised breaking the Sabbath to prevent humanitarian aid from entering Gaza.

“We should be happy that we have a population that cares about Israel and cares about the Sabbath … A war that takes place on the Sabbath makes it permissible to violate the Sabbath,” Mr. Lior decreed.

In March, Rabbi Eliyahu Mali, whose government-subsidised religious seminary in Jaffa aims to dispossess Palestinians still resident in what is today a southern suburb of Tel Aviv that once was Palestine’s most populous city, issued what can only be called an incitement to genocide.

A proponent of permanent Israeli re-settlement of Gaza on religious grounds alongside other ultra-conservative rabbis, including Tzvi Elimelekh Shabaf and David Fendel, Mr. Mali received US$800,000 in government support in 2023.

“The basic rule we have when fighting a holy war, in this case, Gaza, is the doctrine of ‘not sparing a soul.’ The logic of this is very clear. If you don’t kill them, they will try to kill you. Today’s saboteurs are the children of the previous war whom we kept alive,” Mr. Mali, citing scripture, said in a conference at his Shirat Moshe Yeshiva.

Like various forms of ultra-conservative Islam such as Wahhabism, jihadism in the shape of the Islamic State and Al Qaeda, and Hindu and Christian nationalism, militant, supremacist expressions of Judaism represented by religious Zionism in the way it is currently expressed demonstrate the risk of leaving unaltered problematic tenets in religious law.

As the 9/11 attacks did with Islam, Israel’s policy towards the Palestinians shines a spotlight on problematic Jewish religious legal precepts.

Common wisdom says what is needed is pressure on Israel, particularly from the United States and Europe. No doubt, pressure helps, but much like Nahdlatul Ulama has taken the lead in tackling head-on legal, ideological, and religious issues that make Islam part of the problem rather than the solution, Jews will have to do the same for Judaism.

9/11 put Islam’s problems on the front burner. Israel and Jews could face a similar situation as circumstances in the occupied territories, including East Jerusalem, as a result of Israeli policies spin out of control.

The U.S. was born out of ideas and the geopolitical schemes of competing maritime empires, forging a foreign policy approach that dominates its foreign relations today.

Considering whether modern states are empires tells us almost nothing useful about either modern states or empires. A better question is what policies and structures pioneered by empires are still employed by states today, and how.

As the 20th century opened, long-established empires still governed the majority of Eurasia’s territory and population, but they all collapsed by the end of World War I. The European and Japanese colonial empires that escaped destruction then dissolved after World War II. After being the world’s dominant polities for two and a half millennia, empires were now extinct. The term empire itself turned pejorative; polemical rather than analytical. But while empires no longer existed, they left an enduring legacy: sets of distinctive templates for organizing very large polities with diverse populations. They also provided different strategic models for projecting power on the world stage.

Although the United States was the first nation designed on abstract principles of governance rather than inherited institutions, it drew on imperial models to realize them. America’s expansive concept of universal citizenship to unite its diverse population was distinctly Roman in origin, one that emerged in no other empire. American foreign policy, by contrast, employed a distinctly non-Roman maritime empire template that sought economic rather than territorial advantages. While the United States inherited its maritime tradition from Great Britain, in the post-1945 era its international policies bore a stronger resemblance to those of imperial Athens. Athens created the world’s first maritime empire (Arche) in the 5th century BC by building an alliance system to defend the Greeks against Persian aggression. It then used that base to establish an economic sphere in which it was the dominant player, becoming the region’s largest and richest city-state. In a remarkably similar way, the United States also created a postwar military alliance system designed to protect its members from aggression by the Soviet Union that served as a common multinational trading bloc with the American economy at its center.

Citizenship in the United States: E Pluribus Unum

The 18th-century founders of the U.S. were quite familiar with the classical Western history of ancient Greece and Rome. They embraced the principles of democratic governance developed by the Greeks but broke their city-state limitations with the adoption of the Roman imperial model of universal citizenship. As with Rome, American citizenship was designed to transcend existing parochial political identities (in this case America’s original 13 colonies), replacing them with an all-embracing national identity. And again, similar to the Roman Empire, American citizenship would not be restricted by national origin, race, or religion, although such invidious distinctions (particularly race) would play a negative role in the country’s domestic politics. Eager to attract settlers to a land short of labor, the U.S. made the naturalization of foreigners a regular practice and encouraged their immigration to its shores. It automatically conferred citizenship on children born in the country regardless of the status of their parents, precluding the emergence of permanent non-citizen minorities who were residents of a state but without rights in it. The anomaly of allowing a slave population to exist in its Southern states was resolved in a bloody civil war (1861-1865) and subsequent amendments to the Constitution that extended citizenship to all former slaves and their descendants. In 1924, Congress finally passed a law recognizing the country’s original Native American inhabitants as birthright citizens too.

Universal citizenship proved highly effective in uniting a population that had no common origin. The U.S. government was careful never to define “an American” as anything other than a legal category. This was reinforced by the Constitution’s prohibition of any religious tests for serving in public office and vesting rights in individuals rather than communities. It was an imperial way of thinking designed to avoid the religious and ethno-nationalist communal conflicts that plagued Europe. The potential for such conflicts was, and is, never absent in the United States. Existing communities invariably asserted that newer immigrants could never become “real Americans,” only to join with the two generations later to complain about more recent arrivals. In my own city of Boston, the influx of Catholic Irish immigrants provoked violent outrage by Yankee Protestants of English descent. Fifty years later, both English-speaking groups agreed that it was poor non-English speaking Italians and East European Jews who could never become real Americans like themselves. After the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 removed national-origin restrictions, an influx of Asian and Hispanic immigrants provoked renewed concerns that these people would never become real Americans either. Yet by 2018, 14 percent of the U.S. population was foreign-born, close to the record high set in the 1890s, and the once-alien foods they brought with them (from hot dogs to pizza to burritos) became American by popular consumption.

Sustaining America’s Arche

By 1853, the U.S. had taken possession of all the enormous territories between its Atlantic and Pacific coasts; the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867 gave it control of around 10 million square kilometers. Yet despite being one of the largest countries on earth, the United States never viewed itself as a land power. (Even in the 21st century, its demographic and economic centers of gravity remained on the east and west coasts.) Instead, outside of North America, the United States adopted a maritime empire template for its international relations that gave sea power priority over land power, viewed economic hegemony as more desirable than territorial hegemony, and deemed indirect political domination more sustainable than direct political domination when wielding power abroad. By the end of the 19th century, the U.S. would become one of the world’s leading industrial and trading powers, although it had to contend with a domestic tradition of isolationism that was particularly strong after the end of World War I.

The maritime empire template first manifested itself in the 1823 Monroe Doctrine that declared the Americas an exclusive U.S. sphere of influence. This imposed a form of indirect domination by the U.S. over the newly independent states in Latin America and the Caribbean without touching these territories. The three-month Spanish-American War in 1898 was primarily a maritime conflict too. Here, the U.S. Navy fought simultaneously in both the Caribbean and the Pacific, sinking the Spanish fleets based in Cuba and the Philippines and delivering marine expeditionary forces ashore to expel the garrisons defending them.

However, this maritime empire template did not assume global significance until after World War II when the U.S. abandoned its previous isolationism and replaced Great Britain as the West’s dominant power. Its only rival was the Soviet Union. The Soviets followed a typical imperial land power template by taking direct control of all the countries they occupied in Eastern and Central Europe and using proxy regimes to incorporate them into their command economy. By contrast, the U.S. employed an indirect maritime strategy that would have been familiar to the ancient Athenians: seek economic rather than territorial hegemony through an alliance system that protected its member states from aggression and allowed their economies to grow rapidly. Unlike the maritime Athenian Empire, however, the U.S. also possessed a large and self-sustaining domestic economy in North America that could bankroll its high defense spending without extorting payments from its allies, as Athens had unpopularly done.

The U.S. was not interested in recreating a closed trading system with subject colonies like that of the dissolving maritime British Empire. That required both considerable expense and local administrations to maintain. (It also generated anti-colonial political movements, of which the American Revolution had been one of the first.) Instead, the U.S. constructed a postwar international system from which it benefited militarily and economically. The system also benefited its allies enough to make it self-sustaining. The American arche consisted of overlapping networks of military and economic alliances that spanned the globe. The military alliances were designed to provide protection against possible Soviet aggression through mutual defense treaties, including the 1949 North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Western Europe, and bilateral agreements with Japan (1951 and 1960) and Korea (1953) in northeast Asia. These were the linchpins of a system that allowed the stationing of American forces within these sovereign nations, and were part of a much vaster system of secondary alliances that even 30 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union included 800 military bases of various types in 70 countries. Connected by sea and air routes, this network allowed the U.S. to project its power worldwide without maintaining excessively large numbers of troops abroad. Its success in the aftermath of World War II was based on turning former enemies, Germany and Japan, into close allies and major economic powers after installing democratically run governments in these countries and financing their reconstruction.

Buttressed by new global multilateral institutions such as the World Bank (1944), the International Monetary Fund (1945), and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1947), the U.S. supported the creation of the European Common Market (which eventually became the European Union). This was less a matter of altruism and had more to do with the employment of a maritime empire strategy that viewed the emergence of stronger allied partners as a net plus rather than potential rivals. In an improvement on ancient Athens’s approach, the U.S. relied as much on the self-interest of its members to keep the system functioning as it did on its own power. This dual military/economic network would see off the Soviet Union in 1991 and maintain itself afterward. Its success as a strategy was best appreciated by contrasting it with failed U.S. policies that veered from the maritime empire template and drew the country into counterproductive land wars in Vietnam and Iraq.

In one important area, the U.S. broke with the maritime empire template that had created cosmopolitan economies while retaining insular ruling elites in Athens, Venice, Holland, and Great Britain. Universal citizenship, immigration, and capitalist economic disruption combined to produce a political system in the U.S. where the elites who set the U.S. policy eventually reflected the diversity of the population, albeit with a considerable lag time. That diversity was also reflected in America’s soft power influence that was rivaled historically only by Athens in ancient Greece because, beginning in the mid-20th century, the U.S. became the place to be for those producing cultural and scientific innovations. Part of the attraction was its rich economy, secure private property rights, and freedom of expression, but the U.S. also benefited from the arrival of refugee artists, scholars, and scientists fleeing persecution or prejudice in their own homelands. This put the U.S. at the forefront of many fields that the country otherwise would have been unlikely to develop (or develop as quickly) without them. Whether in Hollywood, New York, or Silicon Valley, the ability to attract talented people who became American citizens by choice was an element that was missing in even the most economically cosmopolitan maritime empires of the past. The U.S. was certainly the first to make culture itself a profitable export.

Does understanding which tools a contemporary world power like the U.S. borrowed from extinct empires translate into understanding its global relations today? Yes, because these were grounded in a set of largely unarticulated economic and cultural principles that to them seemed natural and required no explanation and, hence, are often overlooked. For example, in a world where autocracy was the norm, maritime empires (except for Portugal, which was founded by a king) were distinguished by their representative governments. Athens was a democracy, Carthage, Venice, and Holland were republics, and Britain was governed by a parliament. This was a structure in which the state encouraged the accumulation of private wealth and protected it from arbitrary confiscation. Both elements were attractive to the 18th-century founders of the U.S., who combined the limited role of government and respect for private property espoused by John Locke along with an open economy championed by Adam Smith.

The hostility toward autocratic regimes like the former Soviet Union (or Russia today) and the People’s Republic of China displayed by the U.S. is thus better explained by its maritime empire heritage rather than any ideological differences. Autocratic regimes in today’s world seek to achieve stability by creating an equilibrium in which they are dominant—a conservative characteristic of the past empires on which they are modeled. Maritime empires, by contrast, thrived on change. They displayed a higher tolerance for risk and had a propensity to upset existing economic norms—attributes well adapted to modern capitalist economies where no steady-state equilibrium has yet emerged. That, combined with maritime empires’ preferences for alliance building and networks of influence, rather than direct domination, is the international framework in which the U.S. is most comfortable but is also one whose ancient origins have rarely been fully appreciated.

- About the author: Thomas J. Barfield is professor of anthropology at Boston University. His new book, Shadow Empires, explores how distinctly different types of empires arose and sustained themselves as the dominant polities of Eurasia and North Africa for 2,500 years before disappearing in the 20th century. He is a renowned historian of Central Eurasia and the author of The Central Asian Arabs of Afghanistan, The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, 221 BC to AD 1757, Afghanistan: An Atlas of Indigenous Domestic Architecture, and Afghanistan: A Cultural and Political History (revised and expanded second edition 2022, Princeton University Press).

- Source: This article is distributed by Human Bridges, first published in the Sentinel Post.

African-Russian Professor Lily Golden and her excellent thoughtful academic works have been in the historical realm, still considered as foundations to multifaceted relations from the Soviet times until today. During the Soviet era, at the height of political tensions between the West and East, was the period when many African states were in dire need and support for their liberation struggle against deep-seated and widespread colonial tendencies across the continent.

It was the establishment of liberation allied institutions such as the Soviet Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee, and the Soviet Associations Union of Friendship and Intercultural Relationship that enlisted the active participation of Africans from different spheres including including politics, academia, youth and women, culture and sports. African leaders including Julius Nyerere (Tanzania), Nelson Mandela (South Africa), Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana) Sekou Toure (Guinea) Anwar El-Sadat (Egypt) Muammar Gaddafi (Libya) and many others played incredible roles.

In addition, there were worthy activists and academics, contributing tremendously towards consolidating ideas of political liberation and were at the fore-front educating the majority of the young people and the middle-class across Africa. The primary aim was to enhance their understanding of preserving the post-independence political ideals, the necessity to strengthen the relations between Soviet Union/Russia with Africa.

Lily Golden’s Background

Born in Tashkent capital of the republic of Uzbekistan, Professor Lily Oliverovna Golden (1934-2010) was a prominent black Russian social activist, scholar, and mother of Russian TV star Yelena Hanga. She was a daughter of Oliver Golden and Bertha Golden, who immigrated to the Soviet Union from the United States in 1931. Lily’s father died when she was 6 years old. After her father’s death, Bertha Golden and Lily had planned to return to United States, but due to World War II and Bertha’s lingering fears of racism in the United States, they never left Uzbekistan.

Golden’s father, an active member of the American Communist Party, brought a group of 16 black agricultural experts to Tashkent in 1931 to help modernize cotton farming in the rugged, sun-parched fields of Central Asia. The little outpost of African-American emigres was well known and visited by the likes of Langston Hughes and Paul Robeson. Eventually, some of the participants returned to the United States. But others like the Goldens stayed, even though they never found the socialist paradise they had envisioned.

Lily Golden first graduated from high school and attended music school at the Tashkent Conservatory. Later, studied at Moscow State University in 1957 as a historian majoring in African American History. She dedicated her life to teaching and researching in that field. After graduating from Moscow State University, she worked for the Institute of Oriental Studies in a department that focused on African Studies. In 1959, the Soviet Academy of Sciences opened the African Institute where Golden worked for over 30 years, rose through the professional career to become acting director. She published books on Africans living in Russia, African music, and written hundreds of articles.

As a natural fate and as God directed, Tanzanian Abdul Kassim Hanga met Lily Golden for the first time during the 1957 Moscow International Youth Festival. They married three years later when he went back to Moscow to study for a degree in economics at the then newly-opened Peoples’ Friendship University, named after the assassinated Congolese prime minister, Patrice Lumumba.

In the course of developments, Abdul Kassim Hanga was appointed vice-president of the “revolutionary” government. He later became minister for union affairs in the interim union government of Tangan- yika and Zanzibar following the merger between the Republic of Tanganyika and the People’s Republic of Zanzibar on 26 April 1964.

Earlier in 1960, Golden married Abdul Kassim Hanga who was a former vice-president of Tanzania. Abdul and Lily were married for 8 years until Abdul was severely tortured and killed in 1968 by Zanzibar Police. During their marriage, they had one daughter, Yelena Hanga.

According to biographical records, in 1988, Lily Golden moved to the United States and became famous as a black Russian activist, fighting for minority causes and racial harmony. In 1992, she began teaching at Chicago State University in Illinois, where she worked for more than 10 years.

Golden finally returned to Russia in 2003 to be closer to her newly-born granddaughter. She continued to be active in several public organizations. Throughout the remainder of her life, Golden lectured in many countries including Africa, Asia and Europe. In 2003, she published an autobiography about her life as a dark-skinned Russian struggling against changes in Soviet Union called My Long Journey Home.

Landmark Contributions to Russian-African Relations

While back to Moscow, Golden contributed a lot, in terms of, addressing high-level Russian-African conferences and meetings, utilizing the platforms and the opportunity to experience some of the common sentiments of supporting Africa to attain economic sovereignty. In public talks and interactions, she particularly emphasized continental integration and African unity, and invaluable efforts in improving the welfare of the impoverished segments of the population.

On most trips to Africa, she consistently dissipated her energy and willingly shared her experiences, lectured or narrated broadly on aspects of life during turbulent political changes in the Soviet Union under glasnost and perestroika. Golden, with her unusual combination of African, native American and Russian ancestry, became a tower of strength for those fighting against racial bigotry. She contributed to many monographs and academic papers and books, most probably still in the library of the Institute of African Studies.

In 2008 when this article author interacted with Golden in her private apartment, which has a resemblance of an African museum, she explained that “the presence of blacks in Russian culture dates back centuries,” began with the arrival of the black American group to Uzbekistan and further citing an example the father of Russian literature, Alexander Pushkin, who was of African descent. Pushkin’s great-grandfather Hannibal was an Ethiopian prince who served Peter the Great as a general.

Golden seriously advocated for the creation of the Parliamentary Group for the interaction of African legislators, that was during the State Duma chairmanship of Boris Gryzlov. During one of the Parliamentary Friendship Group’s meetings, she presented a comprehensive report which approvingly became part of the main parliamentary working document with Africa. That meeting was attended by Anna Brazhina and Igor Sidorov, both co-founders of the first African media portal – AfricanaRu – set up to document Russia-African information. That State Duma meeting was also attended by the founder of the “African Unity” association Aliou Tounkara, trained in St. Petersburg State University, who is currently a member of parliament in the Republic of Mali.

Parliamentarian Georgy Boos, a Russian businessman and politician, headed this State Duma’s Russia-African Friendship Group which made several trips to African countries, including South Africa, Zimbabwe, Angola, Mali, Ethiopia and Egypt. Boos became a close ally of Mayor Yuri Luzhkov of Moscow, and later drifted from Luzhkov’s centrist Fatherland Party to join United Russia Party.

Golden, with her unusual combination of African-Russian connectivity, became a tower of strength, hope and source of inspiration for African diaspora in the Russian Federation. This experience was helpful to many Africans who suffered racism in the early stages after the collapse of Soviet Union and during the Mayorship of Yury Luzhkov whose discriminatory policy propaganda “Moscow for Moscovites” fueled the rise and activism of nationalists in Moscow city and in St. Petersburg. Racial attitudes and intolerance was at its highest in post-Soviet Russia. Golden, as a result, consistently opposed the slow change of public education, public perceptions through the media to inculcate cultural tolerance and talk against aggressive conservatism.

In comparative terms, Sergei Sobyanin, with pride and selfless zeal for practical transformation, initiated a lot of reforms, tolerating divergent discussions and continue to encourage social-ethnic interactions, these geared towards creating multipolar environment. Sobyanin illustrated his point of an overarching modern city, diversity of multi-ethnic culture, and enforcing the advantages of multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism.

Last Words

Interestingly, in those later years before her death, Golden’s daughter was the only black on TV screen. Yelena Hanga had become Russia’s most popular black television host, at least projecting the blackness and mixed African-Russian skin-colour to Russian thousands of TV audience in the Russian Federation and external viewers. Without much doubts, this has added integrative content to the Russian-African relations.

A distinguished scholar in residence at Chicago State University, Lily is an active member of the board of directors of both the Russian-African Business Council and the San Francisco-based Centre for Citizen Initiatives and Intercultural Black Women’s Studies Institute. She has represented these organizations several times at the UN. Back in Moscow she founded the Golden Foundation of Russian-African Culture.

Golden enjoyed the privileged of upbringing and training that helped to become a leading Soviet academic, and further played various roles in shaping the social and cultural aspects of early stages of the Russian-African relations between 2000 and 2010. Therefore, she still has to be credited for outstanding contributions to the socio-cultural aspects of bilateral partnership. Professor Lily Golden has a special place in history of the relations between Russia and Africa.

In this account of her experiences in this article, Golden provided an unbreakable connection between the contemporary and historical relationships of Africa to Russia. She offered a distinctly different and refreshing point of view of the experiences of Russia in her often alluring and romantic, sometimes bitterly painful, yet always vivid and intimate details of her family life as a dark-skinned Russian surviving in and struggling against turbulent changes. Similarly, Yelena Hanga transmitted an indelible impact on the African diaspora.

Ultimately these symbolic narratives, as mentioned above, challenge the readers of this article to refresh insights and make an positive accessment into building and strengthening future bilateral relations by time and geography. Professor Lily Golden left behind her rich historical tales with charmed (un)erasable policy implications for contemporary Russia and Africa.

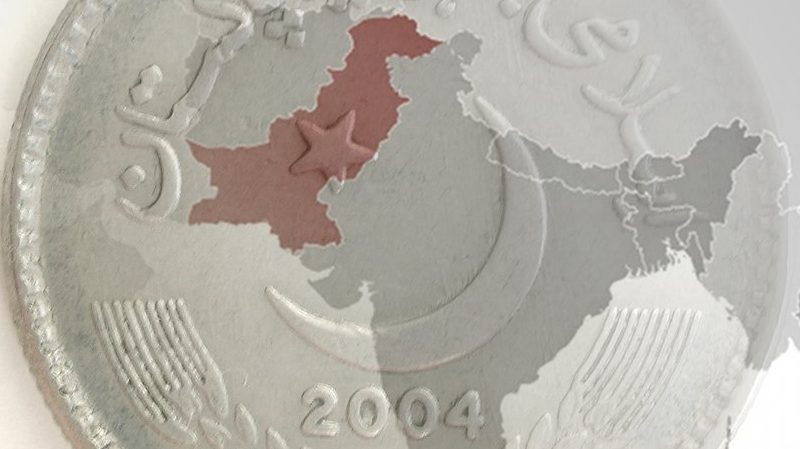

The establishment of the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC) on June 20, 2023, marks a significant step in Pakistan’s ongoing efforts to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and address its economic challenges. As a unified platform aimed at facilitating investors and streamlining decision-making processes, the SIFC has been lauded for its potential to revitalize the country’s commercial landscape. However, the Council’s organizational structure, particularly the prominent involvement of military leadership, raises concerns about the balance of civilian oversight and military influence in economic matters.

The SIFC was conceived during a period of acute economic distress in Pakistan, with the primary goal of creating a more investor-friendly environment. On September 8, 2023, the Apex Committee of SIFC held its fifth meeting, chaired by the Prime Minister and attended by key government officials, including the Chief of Army Staff and Provincial Chief Ministers. This high-level gathering focused on strategies to overcome macroeconomic obstacles, improve governance, and streamline regulations to attract investments. Ministries presented detailed plans to address these challenges, reflecting a comprehensive approach to economic recovery.

Finance Minister Shamshad Akhtar emphasized the interim government’s commitment to economic revival, underscoring the importance of removing import restrictions to reduce dependence on imports. Acting Power Minister Muhammad Ali discussed ongoing negotiations to stabilize electricity prices and plans to auction offshore oil and gas blocks. These discussions indicate a proactive stance towards addressing Pakistan’s economic woes.

The significant involvement of military leadership in the SIFC is both a strategic and pragmatic move. Given Pakistan’s geopolitical landscape, the military’s participation is intended to instill confidence in potential investors, reassuring them of stability and security. This involvement has already yielded positive results, with substantial investment commitments from Gulf countries and other international sources.

However, the military’s role in economic governance is not without its critics. Concerns about the extent of military influence over economic policies and the potential for it to overshadow civilian governance are valid. While the military’s involvement has helped secure investments, it is crucial to ensure that this does not lead to an imbalance where economic policies are predominantly shaped by military interests rather than comprehensive civilian oversight.

Despite these concerns, the SIFC has made notable progress in attracting investments. Foreign Secretary organized an online orientation for Pakistan’s missions abroad to update them on SIFC’s developments. Dr. Jehanzeb Khan outlined the Council’s formation, legal framework, and investment opportunities, urging missions to promote Pakistan’s potential in sectors like Information Technology, Agriculture, Energy, and Mining.

SIFC has already sanctioned several projects and plans to explore joint investment opportunities, including studying lithium availability and corporate agreements. The Council aims to leverage both civilian and military expertise to strengthen its position as a facilitator of economic growth. This integrated approach, combining the strengths of both sectors, is intended to navigate complex economic challenges with agility and resilience.

The dual involvement of civilian and military leaders in the SIFC is designed to harness the complementary strengths of both sectors. This collaborative approach has garnered commendation from various segments of society, including political entities, economic analysts, and media professionals. However, the balance between civilian oversight and military influence must be carefully managed to prevent any undue dominance by the latter.

The military’s involvement, while beneficial in securing investments and providing a stable environment, must be complemented by strong civilian governance to ensure that economic policies are inclusive and sustainable. Long-term policy adjustments are necessary to maintain investor confidence and foster a conducive environment for business growth.

The SIFC represents a strategic amalgamation of expertise from both civilian and military realms, aiming to fortify Pakistan’s investment landscape. This collaborative ethos has been positively received across various sectors of society. Political stakeholders recognize the Council’s proactive efforts in addressing economic constraints and promoting investment-friendly policies. Economists appreciate SIFC’s comprehensive strategies aimed at bolstering economic growth and attracting foreign capital.

Nevertheless, the long-term success of SIFC and Pakistan’s economic revival hinges on sustaining a stable sociopolitical environment and implementing policies that foster business growth. The Council must continue to pursue measures that create, incentivize, and endorse opportunities for economic development.

The establishment of the Special Investment Facilitation Council is a significant step towards economic revival in Pakistan. By facilitating investment and privatization across various sectors, the SIFC embodies the government’s determination to attract both domestic and foreign investment. However, the Council’s success will depend on its ability to maintain a balanced approach between civilian and military oversight, ensuring that economic policies are not disproportionately influenced by any one sector.

The SIFC’s focus on revitalizing the economy through investment in emerging technologies, labor-intensive industries, and other key sectors is promising. However, the real test lies in its ability to sustain long-term economic stability and maintain investor confidence. This requires a concerted effort to foster a supportive environment for business growth, address regulatory challenges, and ensure that the socio-political landscape remains conducive to economic development.

In conclusion, while the SIFC marks a significant step forward for Pakistan, its future success will be determined by how well it manages the delicate balance between civilian and military involvement, and how effectively it can create an environment that encourages sustained economic growth and investor confidence.