Day: May 21, 2024

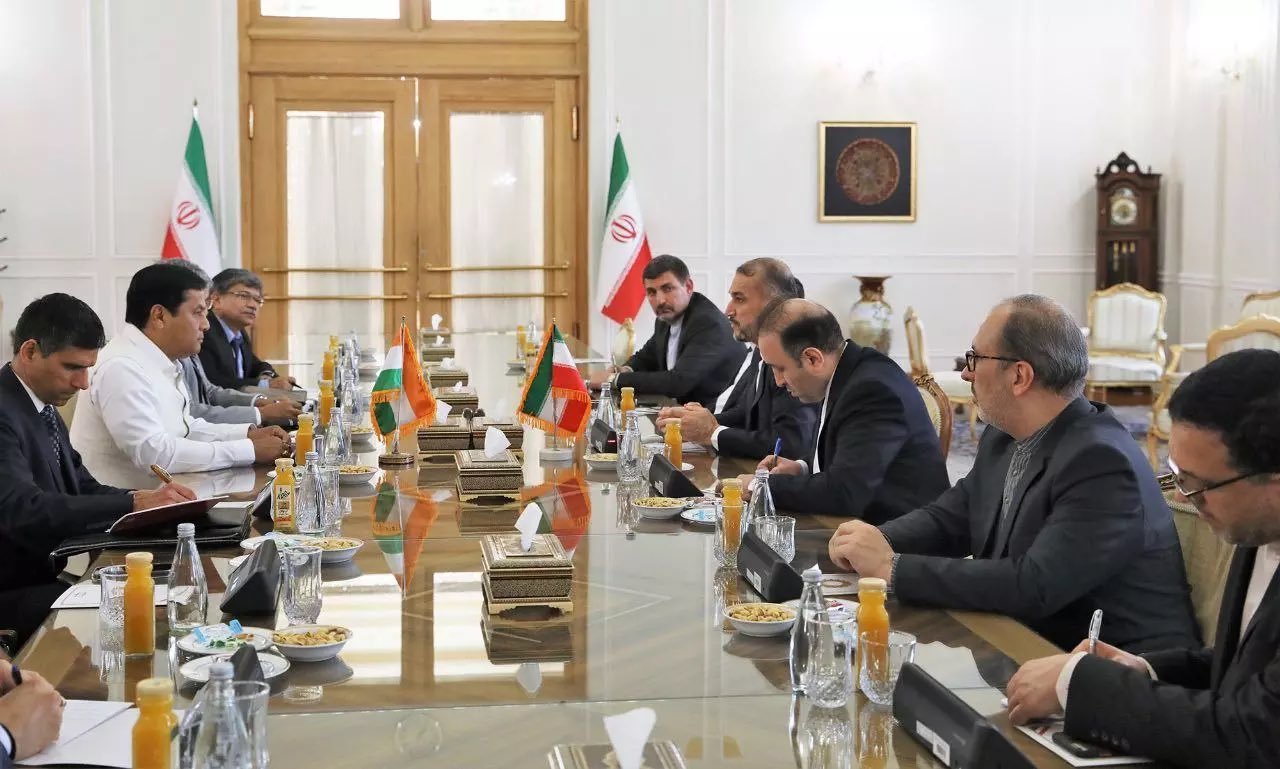

India’s Shipping Minister Sarbananda Sonowal meeting with Iranian officials in Tehran (May 14, 2024, Twitter)

India’s Shipping Minister Sarbananda Sonowal meeting with Iranian officials in Tehran (May 14, 2024, Twitter)

On May 13, 2024, Iran and India signed a historic deal under which New Delhi was granted the right to develop and operate the Iranian port of Chabahar on the Gulf of Oman. India has been eying this port for the past two decades to export goods to Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asian countries and bypass the Chinese-developed ports of Gwadar and Karachi in Pakistan.

What is the significance of this deal for India and Iran?

Commenting on the deal after the signing ceremony in Tehran, India’s Shipping Minister Sarbananda Sonowal said, “Chabahar Port’s significance transcends its role as a mere conduit between India and Iran; it serves as a vital trade artery connecting India with Afghanistan and Central Asian Countries.” Under this agreement, the Indian Ports Global Limited (IPGL) company will invest $120 million in the port with an additional $250 million in financing. Within this context, Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar told reporters in Mumbai that this deal will open the path for new, larger investments to be made in the port.

Meanwhile, Iranian scholar Foad Izadi argued in Induslens that this agreement “holds immense promise as it leverages Iran’s strategic position as a conduit for India’s access to Central Asia and Russia via the North-South Corridor.” Izadi continued that with China’s growing interest in the region, India’s proactive engagement serves as a “strategic countermeasure” aimed at safeguarding its interests and consolidating its economic and political influence. The Iranian scholar added that this agreement is a calculated move on the part of India to “assert its regional presence, capitalize on burgeoning economic opportunities and strategically counterbalance China’s influence.”

For India, cultivating diplomatic and economic relations will maintain its economic growth, Izadi argued. Moreover, with India’s defense exports witnessing a significant rise due to increasing demand, Izadi argued that the Chabahar port could help expand New Delhi’s defense exports. Finally, this deal also reflects India’s autonomous foreign policy, which aims to build new partnerships with rising global powers and consolidate its position “as a discerning and influential player in international affairs.” Of course, this deal may still face challenges. Already, the U.S. State Department deputy spokesperson Vedant Patel argued that Washington will continue enforcing its sanctions against anyone who considers “business deals with Iran.”

It is not surprising that Iran is making a slow but important comeback to the South Caucasus and Central Asia by integrating into regional economic and transport projects. This agreement could further consolidate Iran’s position in the South Caucasus and Central Asia, fortify its role as a regional transit country and strengthen its economic relations with Russia. Meanwhile, by bringing India closer to Russia, Iran will benefit by breaking out of economic isolation and increasing its geo-economic and geopolitical presence in the region. Finally, Iran can use this opportunity to counter U.S. influence in the Persian Gulf and the neighborhood. Notably, the project was unveiled only a few weeks after Turkey, Iraq, Qatar and the UAE announced the ambitious Development Road Project linking the Persian Gulf to Turkey via Iraq, bypassing Iran.

Why does the Chabahar port deal matter for Armenia?

Armenia would also benefit from this agreement. In January 2024, Iran granted access to Armenia to operate in its Chabahar and Bandar Abbas ports to facilitate trade with India. Following the 2020 Artsakh War, Armenia aimed to diversify its security partners and turned to India for defense cooperation and arms purchases. Tehran and New Delhi have been supporting Yerevan’s aspiration to assist in developing and using Iran’s ports. The growth of this trilateral cooperation will significantly improve Armenia’s transit infrastructure and elevate each country’s geo-economic importance in the South Caucasus within the context of the Black Sea – Persian Gulf Corridor. In 2023, Armenia’s former deputy Foreign Minister Mnatsakan Safaryan said that the Chabahar port is an integral component in Armenia’s quest to have access to Indian and Asian markets via the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC). As Yerevan projects itself as a transit country for Iran and India to the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and European markets, its economy will boost significantly from international trade.

Commenting on this agreement, the Yerevan-based Armenia-India Business Council (AIBC) said, “This strategic alliance not only underscores the deepening economic cooperation between India and Iran but also underscores India’s strategic vision of enhancing connectivity and trade facilitation in the region.” The Council also stated that this deal also opens new opportunities for Armenian importers and businesses and will boost trade between Yerevan and New Delhi.

In parallel to finalizing an agreement between Moscow and Tehran to construct the remaining section of the railway connecting Azerbaijan to Iran, Tehran is also eager to bring Armenia on board. In October 2023, Yerevan and Tehran signed an agreement under which Iranian construction firms will build a 32 km road in the southern section of Armenia’s North-South Transport Road Corridor. This road will connect the town of Kajaran to the village Agarak in Syunik. It will include 920 m of tunnels, five interchanges, six overpasses and 17 bridges. The construction is estimated to be finalized by 2026, with the Armenian government borrowing $254 million from the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development and granting a $215 million contract to a consortium of two Iranian companies for the project. About two-thirds of the road will be expanded and renovated while the remaining 11 km will be built over the course of three years.

This initiative will shorten the travel time between both countries and is part of Armenia’s ambitious project to serve as a bridge between Iran and Georgia and link the Black Sea ports to that of the Persian Gulf. This road has strategic significance for Armenia as it could consolidate Armenia’s security and bring stability to the region. Finally, Armenia’s participation in this transit project will increase the country’s geo-economic importance along regional transit routes, ease its isolation and balance the Turkish-Azerbaijani axis by benefitting from Iran and India’s proactive role and engagement in the South Caucasus.

Author information

Yeghia Tashjian

Yeghia Tashjian is a regional analyst and researcher. He has graduated from the American University of Beirut in Public Policy and International Affairs. He pursued his BA at Haigazian University in political science in 2013. In 2010, he founded the New Eastern Politics forum/blog. He was a research assistant at the Armenian Diaspora Research Center at Haigazian University. Currently, he is the regional officer of Women in War, a gender-based think tank. He has participated in international conferences in Frankfurt, Vienna, Uppsala, New Delhi and Yerevan. He has presented various topics from minority rights to regional security issues. His thesis topic was on China’s geopolitical and energy security interests in Iran and the Persian Gulf. He is a contributor to various local and regional newspapers and a presenter of the “Turkey Today” program for Radio Voice of Van. Recently he has been appointed as associate fellow at the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut and Middle East-South Caucasus expert in the European Geopolitical Forum.

The post What does the India-Iran Chabahar port deal mean for Armenia? appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Lala Yerem performing

Lala Yerem performing

Lala Yerem is an inspiring vocal magician. Her singing style sends chills down your spine and invokes your being to wake up and be active in the Armenian struggle. I saw Lala perform at a May 28 event and was in awe. I was also lucky enough to hear her sing at an event a few weeks ago and felt a revival of my spirit again.

Lala is a revolutionary (heghapokhagan) songstress. She was born in Iran to a patriotic Armenian family. She studied at Armenian schools, went to Armenian clubs and was an active member of Homenetmen as a girl scout and an AYF member. She grew up embracing her culture through music, dance and poetry, but patriotic songs had a special place in her heart. From a young age, she made songbooks of patriotic songs which she performed at Armenian events. After getting her bachelor’s in Armenian language and literature, she moved to Armenia and got her master’s in Armenian history at Yerevan State University. In the meantime, Lala enrolled in the State Song Theater of Armenia to further her singing.

When she moved to Oregon, Lala thought her singing of Armenian patriotic songs would end, until one day she was invited to a party hosted by Don Latarsi, the head of guitar studies at the University of Oregon School of Music. Many musicians were invited to that party, including Mason Williams. Lala sang the “Soldier’s Song” (Mardigi Yerkeh) acapella. Everyone was chatty and loud, but the minute she started singing, there was absolute silence. The next morning, she got a call from Mason Williams. He introduced her to Diane Retalic, an Armenian who was the director of the Eugene Concert Choir. Lala joined the choir, where she sang for four years. She also performed a few Armenian folk and patriotic songs with the accompaniment of Don Latarski. “The interpretation of these songs with the language of jazz was unique,” commented Lala.

In 2018, Lala moved to Los Angeles, California. She continued to sing with her friends at private gatherings. Performing was in the past for Lala, until the 2020 Artsakh War changed everything. Shortly after the war, Lala was invited by one of her ungerouhis to sing heghapokhagan songs. “Even though I was so devastated by the war, I wanted my songs to inspire. It was no longer about my desire to sing. It was now a necessity, my way of continuing the struggle,” Lala said. After that event, Lala and her band did multiple events in the Los Angeles and Orange County communities and an event in New York City.

“I saw the impact. I felt the impact of my songs. I love to invite people to sing with me, because I know the power of these songs. We need to sing together, because the impact is even stronger,” Lala reflected.

The caliber of Lala’s voice is full of hope. These songs are part of our mindset to continue our baykar, our struggle. “There is a war on our history, our identity, our culture, and I can’t not fight. I can fight with my songs. We all have a way that we can fight for ourselves. These songs are part of our history, part of our identity. The enemy is well aware of the power of these songs. That’s why these songs are continuously being attacked as hostile and too extreme. What could be more hostile than the genocide that our enemy has committed towards the Armenian nation many times? The enemy wants us to think we are weak. We are not weak. We are a very powerful and strong nation, within Armenia and the diaspora. Every one of us can fight in our own way, whether it’s through songs, books or education. Whatever inspires you to help our nation, do it. Rise and fight in whatever way you can. Do whatever you can with what you have to help,” Lala concluded.

Author information

Talar Keoseyan

Talar Keoseyan is a mother, educator and writer.

The post Lala Yerem on continuing the Armenian struggle through song appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

By Yunis Sharifli

Since 2022, Uzbekistan has faced an energy shortage with significant political and economic consequences. Despite its gas reserves, the country has transitioned from an energy exporter to an energy importer. A terminal decline in domestic gas production and a lack of significant discoveries of new deposits, coupled with aging infrastructure, have led to the energy shortages, particularly in the winters of 2022 and 2023 (Interfax, February 22; Daryo, March 27).

Cogeneration plants running on gas produce almost 85 percent of Uzbekistan’s electricity. In this regard, the gas shortages and growing electricity crisis have forced thousands of industrial workers into temporary layoffs and fueled public discontent (Eurasianet, December 9, 2022; CABAR.asia, January 1, 2023; see EDM, April 18, 2023). The gas shortage in Uzbekistan could lead to further discontent in the population’s future, and Tashkent’s growing alliance with Moscow may play a role in the tense geopolitical environment in the region.

In Tashkent alone, approximately 6,000 wholesale gas customers were disconnected from the national gas network, and 120 out of 584 neighborhoods experienced frequent and prolonged power and gas outages during the winter of 2023 (Eurasianet, January 16, 2023). The government has adopted a multi-pronged strategy to address the growing energy crisis, including importing gas from various countries, including Russia and Turkmenistan. Uzbekistan’s share of imported gas rose from $50.4 million in 2020 to $695 million in 2023, reflecting a growing reliance on external sources to meet domestic demand (Daryo, March 27).

Three critical reasons underscore Uzbekistan’s move to increase its gas imports from external sources. First, domestic gas production is declining. Uzbekistan’s gas production fell from 22.01 billion cubic meters (bcm) in January–May 2022 to 19.86 bcm during the same period in 2023. In addition, production fell to 11.59 bcm in January–March 2024 (Stat.uz, June 20, 2023; April 22). Depleted gas reserves and infrastructure failures have led to this decline, prompting Tashkent to seek energy imports to address the shortages.

The second reason is the growing energy consumption in Uzbek households. The population’s share of total energy consumption increased from 26.4 percent in 2016 to 28.9 percent in 2022. Calculations suggest that the population’s demand for electricity could grow from 5 to 5.3 percent annually until 2035 (Kun.uz, February 1, 2023). In addition, industrial growth is driving gas imports. By the end of 2023, industrial production had increased by 6 percent (Azernews, February 23). The industry sector alone consumed nearly 40 percent of Uzbekistan’s electricity production in 2019 (International Energy Agency, April 2020). Rising household and industrial energy consumption coupled with declining domestic gas production have increased Uzbekistan’s need for gas imports.

Factors outside the country are critical to Uzbekistan’s energy imports, particularly its commitment to export gas to China. Despite domestic gas shortages that resulted in zero gas exports to China in the first quarter of 2023, Tashkent is working to find alternatives for meeting its contractual obligations (see EDM, April 18, 2023: Kun.uz, March 29). Uzbekistan’s gas exports to China fell from $1.07 billion in 2022 to $563.5 million in 2023, a decline of nearly 50 percent (Gazeta.uz, January 2022). In this context, Uzbekistan’s increasing gas imports may be related to fulfilling its contractual obligations without gas disruptions and preventing damage to relations with China.

Over the past few years, Uzbekistan has signed major gas agreements with Turkmenistan and Russia. In 2023, Tashkent and Ashgabat signed a contract to supply Uzbekistan with up to 2 bcm of Turkmen gas (Kun.uz, August 25, 2023). In addition, Uzbekistan reached an agreement with Russian majority state-owned oil and gas company Gazprom to purchase 2.8 bcm of natural gas annually (Kun.uz, March 7). Tashkent appears to be particularly interested in importing Russian gas, with plans to nearly quadruple imports by 2026, reaching 11 bcm per year via Kazakhstan. Long-term gas talks between the two parties are ongoing (Trend News Agency, February 13). Uzbekistan also plans to modernize its main gas pipeline system between 2024 and 2030, particularly in the northern direction, reflecting the country’s growing interest in Russian gas (UzDaily, March 5).

Two primary reasons explain Uzbekistan’s interest in importing more Russian gas. First, Tashkent harbors doubts about the reliability and sustainability of Turkmen gas imports, as evidenced by Turkmenistan’s export cuts to Uzbekistan in January 2023 due to technical problems (Kun.uz, January 18, 2023). Second, Russian gas is more reliable than Turkmen gas and would play a stabilizing role in resolving Uzbekistan’s gas shortage issue. Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, Russia has turned to Asian gas markets due to reduced exports to Europe. The Uzbek need for gas provides Russia with a new market to partly supplement these losses (The Moscow Times, January 26, 2023).

Uzbekistan’s Minister of Energy Jurabek Mirzamahmudov stated that the import of Russian gas should not be politicized and that it is a “commercial relationship.” He asserted that the Uzbek market needs additional gas supplies from somewhere, and Russian gas can fill this gap (Gazeta.uz, November 29, 2023). Additionally, Moscow’s mounting pressure on Uzbekistan has led Tashkent to view increased imports of Russian gas as a way to alleviate political pressure and maintain stable relations.

Both internal and external reasons motivate Tashkent to increase the import of natural gas from external sources, specifically Russia. Importing more gas, however, has positive and negative implications for the country’s political and security environment. On a positive note, importing additional gas will allow Uzbekistan to keep a balance between supply and demand in ameliorating energy shortages, reduce the possibility of any explosion of public discontent, and continue the country’s economic growth. In contrast, increasing dependency on imports from external countries, particularly Russia, creates new security vulnerabilities. Without reducing this dependence and expanding the use of diverse energy sources for power generation, Increased reliance on Russia gives Moscow more leverage over Tashkent, complicates Uzbekistan’s pursuit of a more balanced foreign policy, and risks cuts to energy imports when relations are particularly strained.

- About the author: Yunis Sharifli is a research fellow at the Central Asia Barometer. His research areas cover Chinese foreign policy in the context of Beijing’s relations with Russia and Central Asia. He also works as a junior research fellow at the Caucasian Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies (QAFSAM) in Azerbaijan.

- Source: This article was published at The Jamestown Foundation’s Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 77

By Yunis Sharifli

Since 2022, Uzbekistan has faced an energy shortage with significant political and economic consequences. Despite its gas reserves, the country has transitioned from an energy exporter to an energy importer. A terminal decline in domestic gas production and a lack of significant discoveries of new deposits, coupled with aging infrastructure, have led to the energy shortages, particularly in the winters of 2022 and 2023 (Interfax, February 22; Daryo, March 27).

Cogeneration plants running on gas produce almost 85 percent of Uzbekistan’s electricity. In this regard, the gas shortages and growing electricity crisis have forced thousands of industrial workers into temporary layoffs and fueled public discontent (Eurasianet, December 9, 2022; CABAR.asia, January 1, 2023; see EDM, April 18, 2023). The gas shortage in Uzbekistan could lead to further discontent in the population’s future, and Tashkent’s growing alliance with Moscow may play a role in the tense geopolitical environment in the region.

In Tashkent alone, approximately 6,000 wholesale gas customers were disconnected from the national gas network, and 120 out of 584 neighborhoods experienced frequent and prolonged power and gas outages during the winter of 2023 (Eurasianet, January 16, 2023). The government has adopted a multi-pronged strategy to address the growing energy crisis, including importing gas from various countries, including Russia and Turkmenistan. Uzbekistan’s share of imported gas rose from $50.4 million in 2020 to $695 million in 2023, reflecting a growing reliance on external sources to meet domestic demand (Daryo, March 27).

Three critical reasons underscore Uzbekistan’s move to increase its gas imports from external sources. First, domestic gas production is declining. Uzbekistan’s gas production fell from 22.01 billion cubic meters (bcm) in January–May 2022 to 19.86 bcm during the same period in 2023. In addition, production fell to 11.59 bcm in January–March 2024 (Stat.uz, June 20, 2023; April 22). Depleted gas reserves and infrastructure failures have led to this decline, prompting Tashkent to seek energy imports to address the shortages.

The second reason is the growing energy consumption in Uzbek households. The population’s share of total energy consumption increased from 26.4 percent in 2016 to 28.9 percent in 2022. Calculations suggest that the population’s demand for electricity could grow from 5 to 5.3 percent annually until 2035 (Kun.uz, February 1, 2023). In addition, industrial growth is driving gas imports. By the end of 2023, industrial production had increased by 6 percent (Azernews, February 23). The industry sector alone consumed nearly 40 percent of Uzbekistan’s electricity production in 2019 (International Energy Agency, April 2020). Rising household and industrial energy consumption coupled with declining domestic gas production have increased Uzbekistan’s need for gas imports.

Factors outside the country are critical to Uzbekistan’s energy imports, particularly its commitment to export gas to China. Despite domestic gas shortages that resulted in zero gas exports to China in the first quarter of 2023, Tashkent is working to find alternatives for meeting its contractual obligations (see EDM, April 18, 2023: Kun.uz, March 29). Uzbekistan’s gas exports to China fell from $1.07 billion in 2022 to $563.5 million in 2023, a decline of nearly 50 percent (Gazeta.uz, January 2022). In this context, Uzbekistan’s increasing gas imports may be related to fulfilling its contractual obligations without gas disruptions and preventing damage to relations with China.

Over the past few years, Uzbekistan has signed major gas agreements with Turkmenistan and Russia. In 2023, Tashkent and Ashgabat signed a contract to supply Uzbekistan with up to 2 bcm of Turkmen gas (Kun.uz, August 25, 2023). In addition, Uzbekistan reached an agreement with Russian majority state-owned oil and gas company Gazprom to purchase 2.8 bcm of natural gas annually (Kun.uz, March 7). Tashkent appears to be particularly interested in importing Russian gas, with plans to nearly quadruple imports by 2026, reaching 11 bcm per year via Kazakhstan. Long-term gas talks between the two parties are ongoing (Trend News Agency, February 13). Uzbekistan also plans to modernize its main gas pipeline system between 2024 and 2030, particularly in the northern direction, reflecting the country’s growing interest in Russian gas (UzDaily, March 5).

Two primary reasons explain Uzbekistan’s interest in importing more Russian gas. First, Tashkent harbors doubts about the reliability and sustainability of Turkmen gas imports, as evidenced by Turkmenistan’s export cuts to Uzbekistan in January 2023 due to technical problems (Kun.uz, January 18, 2023). Second, Russian gas is more reliable than Turkmen gas and would play a stabilizing role in resolving Uzbekistan’s gas shortage issue. Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, Russia has turned to Asian gas markets due to reduced exports to Europe. The Uzbek need for gas provides Russia with a new market to partly supplement these losses (The Moscow Times, January 26, 2023).

Uzbekistan’s Minister of Energy Jurabek Mirzamahmudov stated that the import of Russian gas should not be politicized and that it is a “commercial relationship.” He asserted that the Uzbek market needs additional gas supplies from somewhere, and Russian gas can fill this gap (Gazeta.uz, November 29, 2023). Additionally, Moscow’s mounting pressure on Uzbekistan has led Tashkent to view increased imports of Russian gas as a way to alleviate political pressure and maintain stable relations.

Both internal and external reasons motivate Tashkent to increase the import of natural gas from external sources, specifically Russia. Importing more gas, however, has positive and negative implications for the country’s political and security environment. On a positive note, importing additional gas will allow Uzbekistan to keep a balance between supply and demand in ameliorating energy shortages, reduce the possibility of any explosion of public discontent, and continue the country’s economic growth. In contrast, increasing dependency on imports from external countries, particularly Russia, creates new security vulnerabilities. Without reducing this dependence and expanding the use of diverse energy sources for power generation, Increased reliance on Russia gives Moscow more leverage over Tashkent, complicates Uzbekistan’s pursuit of a more balanced foreign policy, and risks cuts to energy imports when relations are particularly strained.

- About the author: Yunis Sharifli is a research fellow at the Central Asia Barometer. His research areas cover Chinese foreign policy in the context of Beijing’s relations with Russia and Central Asia. He also works as a junior research fellow at the Caucasian Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies (QAFSAM) in Azerbaijan.

- Source: This article was published at The Jamestown Foundation’s Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 77

The shift in France’s policies towards the eastern flank of Europe is real. It entails a profound reassessment of security threats and geopolitical challenges, and of the answers they require.

By Teona Giuashvili

This paper traces the evolution of French policy towards eastern Europe following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It explores the main drivers of the remarkable shift in France’s posture, priorities and narrative, and asks whether it amounts to a tactical adjustment or a strategic turning point. The paper finds that France’s policy shift is real and informed by a new assessment of the transformed European strategic context. At the same time, French commitment to resisting Russia and strengthening ties with partners in central and eastern Europe is part of its long-standing endeavour to reinforce European sovereignty and defence policy. If the requirements to achieve it have changed, the ultimate goal has not.

Analysis

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has transformed Europe’s strategic landscape. In response to the return of large-scale war on the continent, Europeans have broken long-standing taboos, including the provision of advanced weaponry to help Ukraine push Russia back and the decision to launch a new phase of the enlargement process of the European Union. While all EU Member States have adjusted their stance and priorities to cope with the war in Ukraine, not many have embraced such a radical change as France.

Today, France stands as one of Ukraine’s firmest allies in Europe, determined to obstruct Russia’s war effort, provide humanitarian, financial and military support to Ukraine and contribute to its reconstruction. France endorsed Ukraine’s prospective EU membership and, to the surprise of many, threw its weight behind Ukraine’s NATO accession. This stance stands in striking contrast to the French position not only before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, but also in the immediate aftermath of the attack. These changes have sparked considerable debate among diplomats and pundits as to whether they should be seen as a gradual transition or a drastic shift, a tactical adjustment or a strategic choice, a consistent pattern or an ambivalent position.

This paper does not confine itself to contrasting France’s current posture with its traditional policy towards eastern Europe but aims to explore the main drivers of its policy shift. It looks in particular at five major dimensions of change: responding to Russia’s predatory behaviour, endorsing the prospect of EU enlargement to encompass Ukraine, establishing a new level of dialogue with countries in central and eastern Europe, backing Ukraine’s bid to join NATO and asserting a ‘whatever it takes’ stance to defeat Russia in Ukraine. The paper addresses two main questions, namely whether the evolution of French rhetoric has been matched by subsequent action, and whether policy change corresponds to an incremental evolution in France’s posture or amounts to a turning point, a Zeitenwende. To answer these principal questions, this policy paper builds on numerous interviews conducted with French officials and experts.[1]

1. Shaping France’s new approach to Russia and eastern Europe

France has come a long way from its traditional Russia-centric approach to eastern Europe, by taking the lead in countering Russia to defend Europe. Efforts to engage with Russia have been one of the fixed features of French foreign policy for decades. At the core of France’s Russia policy was a ‘mythologised perception’ of Russia’s European destiny and the West’s ‘failure’ to embrace and accommodate it. France’s search for autonomy and leadership in Europe, coupled with the ambition to conduct an independent, ‘neither aligned nor vassalised’, foreign policy and to balance American influence led elites in Paris to favour a cooperative approach towards Moscow. As a permanent member of the UN Security Council and a nuclear power, Russia was viewed as a great power in a multipolar world and, more recently, as a potentially instrumental means of containing the rise of China.

By conferring a special place and status to Russia however, Paris marginalised the independent states bordering Russia in its strategic thinking. It is through the Russian prism that France viewed and approached young democracies in eastern Europe in ways that would not undermine its relations with Moscow. This approach included both self-delusion concerning Russia’s intentions towards its neighbours and a degree of tacit understanding of the Kremlin’s determination to maintain a ‘sphere of influence’ in its ‘near abroad’.

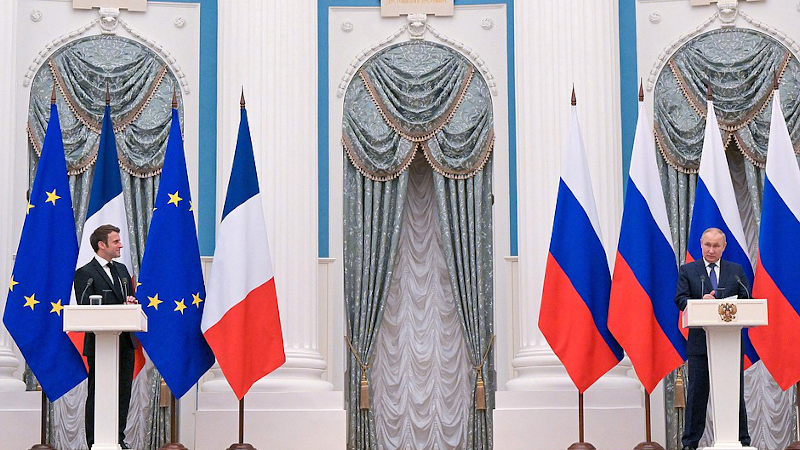

Against this background, President Macron’s foreign policy towards Moscow, rooted in the inherited formula of ‘dialogue and firmness’, appeared to lean more towards dialogue than firmness. The French President sought to position France at the forefront of efforts to ‘reinvent an architecture of security and confidence’ in Europe, which would include Russia. Overall, President Macron’s foreign policy and approach to Russia reflected France’s self-perception as a ‘balancing power’ (‘puissance d’équilibres’), claiming ‘freedom to act’ and flexibility beyond the constraints of East-West competition.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, President Macron was quick to stress that the attack marked ‘a turning point in the history of Europe and of our country’. France unequivocally condemned the aggression and readily contributed to shaping the EU’s response to it. The far-reaching implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine for the European and the international order progressively surfaced in the French strategic debate, leading to successive policy shifts, each further distancing France’s stance from its earlier position.

The first major shift came in late spring of 2022, when Paris formally decided to support Ukraine’s EU accession bid – a startling decision considering France’s earlier reluctance to envisage any step conducive to further EU enlargement towards associated countries in eastern Europe (Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine). More broadly, France’s change of heart and tone towards central and eastern Europe translated into a new attitude of listening and dialogue with partners in the region, epitomised by Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the GLOBSEC meeting in Bratislava in May 2023. In his discourse, the French President acknowledged that the painful historical memories and warnings of these countries had not been sufficiently recognised and heard.

A few weeks later, the NATO Vilnius Summit held in July 2023 marked two further important shifts in France’s overarching approach to the region. Emmanuel Macron announced the decision to supply long range (SCALP-EG) cruise missiles to Ukraine, and further intensified the delivery of ammunitions, weapons and armed vehicles. Where France broke most strikingly from its long-standing position however was on the issue of NATO enlargement. In the run-up to the NATO Vilnius Summit, the French president declared himself open to the idea, until then deemed unthinkable in Paris, of supporting Ukraine’s (post-war) accession to NATO.[2]

Macron’s solidarity with Ukraine attained a new high in early 2024, with the situation on the ground deteriorating, America’s support for Ukraine stalled in the US Congress, and Europe’s geopolitical self-confidence began turning into angst. The French President made it clear that the ‘defeat of Russia is indispensable to the security and stability of Europe’. He pledged to stand alongside Ukraine resolutely, with partners, ‘for as long as necessary and whatever it takes’. As a concrete manifestation of the ‘strategic leap’ he was advocating, he went so far as to not rule out the deployment of allied troops to Ukraine and refusing to set limits when determining how to respond to Russia’s aggression.

2. Principal drivers of change

The concise overview of the main developments in France’s policy response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine illustrates the extent of the shift compared to pre-war positions. Assessing the wider implications of this evolution requires a closer scrutiny of its principal drivers. Officials maintain that these changes are not merely tactical adjustments but reflect the development of France’s strategic thinking on European security against a dramatic new security backdrop that carries unprecedented threats.

2.1. Reacting to Russia’s predatory behaviour

Russia’s predatory behaviour is an important factor in explaining the reversal of France’s stance following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. Russia upset the ‘delicate equilibrium’ that France strove to sustain in its ‘strategic relationship’ with Moscow. As Russia crossed all imaginable political, moral and security boundaries with its full-scale aggression towards Ukraine, it triggered a reassessment in Paris of the nature of Putin’s regime and the need to avert Russian victory. Whereas France used to advocate a European security architecture embracing Russia, today there is a clear understanding that such a European security system should be built without, if not against, Russia.

This change did not immediately follow Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. After the attack in February 2022, France sought to leave a door open for dialogue with Putin. Officials maintain that the rationale behind President Macron’s continued diplomatic overtures to Russia was to exhaust all the possibilities for a diplomatic solution. Such efforts would also be essential to demonstrate to the Global South and the international community at large that the West was not rejecting the use of diplomacy to bring the conflict to an end, thereby invalidating Russia’s claims about Western hostility. They would help domestically too, showing to the French public that Emmanuel Macron was striving for peace, while standing up to aggression. As France sought to keep dialogue open however, evidence of Russia’s widespread war crimes began to emerge, and civilian targets were bombed on a significantly larger scale. Paris came to realise the futility of dialogue with Moscow and the need to take a tougher stance. Officials have remarked that as attempts at diplomatic engagement failed, France adjusted its approach but not its underlying objectives, namely preserving the security of the European continent, supporting Ukraine’s sovereignty and defending the fundamental principles of international law.

The French authorities addressed the implications of Russia’s aggressive stance not only in Ukraine but also at home. Russia has been carrying out hybrid campaigns to interfere in France’s domestic politics and harm the integrity of its democratic institutions and processes for many years. Since February 2022, Russia has significantly increased its subversive operations, propaganda and disinformation activities, in an attempt to undermine societal cohesion, overturn France’s support for Ukraine and influence the results of the elections to the European Parliament in June. Russia has become a domestic threat to France.

As well as meddling in French politics, Russian propaganda and information warfare have targeted France in the Sahel region too. The Wagner mercenary group was instrumental in exploiting historic resentments and exacerbating anti-French sentiments in this region. Encroachments in a number of countries (the Central African Republic, Mali, Burkina Faso, Chad and Niger) have enabled Russia to increase its influence in the region, in addition to gaining access to lucrative mining assets in exchange for protecting the local regimes.

2.2. At the forefront of EU enlargement and reform

Enlargement has been the most successful tool for inducing political, economic and social advances in the countries aiming to join the EU. However, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Kyiv’s application for EU membership, it has acquired broader strategic significance. Opening the prospect of accession to Ukraine revived the process for countries in the western Balkans too, likewise Moldova and Georgia. Strategic, political and institutional considerations led Paris to embrace the prospect of EU enlargement – something experts have described as France’s Copernican revolution.

France, together with other EU Member States, came to view enlargement as a response to the geopolitical challenges facing the continent. For one thing, Paris perceived it as a contribution to the long-term resilience of Ukraine and other neighbouring states and therefore to European stability. For another, it framed enlargement as one of the main vectors for the EU to assert itself as a strategic actor in its immediate neighbourhood. Then foreign minister Catherine Colonna underscored the geopolitical imperative of enlargement: ‘Ukraine will be stronger and Europe will be strengthened by Ukraine’. In addition to geopolitical considerations, Paris was always clear that the prospect of enlargement to incorporate several new Member States would raise the question of the EU’s own reform. Reforming Europe’s institutions and policies has been central to President Macron’s vision of Europe since his landmark Sorbonne speech in 2017. Seven years on, in his second Sorbonne speech on Europe, he reaffirmed the need to ensure the ‘anchoring’ of Ukraine, Moldova and the western Balkans in Europe while simultaneously reforming the EU.

From a French perspective, the process of enlargement will in all likelihood extend over many years. Given this assumption, the urgency of meeting Ukraine’s expectations for stronger political engagement and to aligning all European countries against Russia’s aggression prompted Emmanuel Macron to propose the launch of the European Political Community (EPC). In contrast to François Mitterrand’s precursory idea of a ‘European confederation’, the political aim of the EPC was to isolate Moscow and to re-think Europe’s political and security architecture without Russia.

2.3. France in central and eastern Europe: in search of lost time

A year after the beginning of the war, President Macron’s Bratislava speech marked a milestone in France’s recalibration of its relationship with the countries of central and eastern Europe. It was a self-reflective and, in some respects, repentant moment, but also an attempt to renew France’s leadership in Europe.

The foremost driver behind this change in tone and approach was France’s intention of restoring its strategic credentials in the region. Seen from Paris, the disagreement with central and eastern European countries was not about a divergent perception of the threats stemming from Russia, but about the ways to manage them. For the countries in central and eastern Europe however, lack of confidence in France’s commitment to the region is rooted in both distant and recent historical memories, and the feeling that their warnings against the threat posed by Russia had been ignored. Some controversial statements by President Macron since February 2022, when he called for ‘not humiliating Russia’ or contemplated ‘offering security guarantees to Russia’ compounded France’s credibility deficit in the eyes of many in eastern Europe. In Bratislava, Emmanuel Macron took it upon himself to reverse such scepticism and define a new political basis to build confidence and partnerships with eastern Europe.

The second driver behind President Macron’s outreach to this region was his determination to foster France’s role in a changing Europe. Paris did not share the view that the continent’s political centre of gravity was moving eastwards following the validation of eastern Europe’s assessment of the danger posed by Russia. France’s move was rather informed by the recognition that enhancing Europe’s unity and sovereignty – the overarching ambition of Emmanuel Macron’s foreign policy – could not be achieved without eastern European partners on board. Paris realised that more intense dialogue with them was necessary to shape EU consensus, albeit ultimately a consensus around French ideas.

In addition to these primary drivers, France’s complicated relationship with Germany and, following Brexit, with the UK, also played a role in France’s recalibration of its leadership in Europe. Stalemate in the Franco-German tandem encouraged Paris to seek new partners among central and eastern European allies to amplify its voice. France might have also felt outperformed by the UK, an actor whose strategic outlook has traditionally been close to that of eastern Europeans, and which played an important role in supporting Ukraine at the outset of the war.

2.4. A step change on NATO

Emmanuel Macron’s decision to reconsider France’s long-standing opposition to NATO’s ‘open door policy’ and to offer support for Ukraine’s bid to join the Atlantic Alliance surprised many, both in allied countries and within the French administration. No one expected that the president, who only four years earlier had proclaimed NATO ‘brain dead’, would favour expanding NATO to the East at such a precarious time for Europe. The French pivot distanced Paris from Berlin, but also from Washington and London and aligned it with Ukraine’s staunch supporters in eastern Europe, Poland and the Baltic states.

Sceptics felt that an opportunistic logic drove the French U-turn, as a move to curry favour with Ukraine and eastern European partners while knowing that, in the current circumstances, the US and Germany would oppose NATO’s enlargement to Ukraine. Others, equally unconvinced, found Emmanuel Macron’s support for Ukraine’s NATO accession of little consequence in practice, given that the enlargement of NATO (and the EU) is a long drawn-out process, advancement in which depends on a combination of multiple factors, each capable of putting the process on hold. However, French diplomats deny that opportunistic or transactional motivations influenced France’s stance on Ukraine’s NATO accession. They maintain that the French shift on NATO enlargement is evidence of the determination in Paris to ensure that Russia fails and to guarantee Ukraine’s security.

As the war grinds on, tactical, strategic and political considerations made Ukraine’s NATO accession the best of available options for Paris. France was one of the first countries to join the G7 pledge to support Ukraine, including through bilateral, long-term security assurances. However, the prospect of Kyiv’s membership of NATO would ensure American commitment to Ukraine’s defence, together with the European allies. The security guarantees provided by Article 5 would be the most politically viable, economically tenable and the safest way of sustaining Ukraine’s defence, compared to other existing arrangements for military assistance, such as the Israeli or the South Korean models. In short, Paris views this option as the only credible way to deter further Russian aggression against Ukraine. Another consideration that might have motivated the French initiative is strengthening Kyiv’s position in negotiations with Moscow when, depending on the situation in the field, the time comes to enter talks.

The strategic imperative of defending Ukraine also derives from the recognition of Ukraine’s EU membership prospects. Given that France chose to support Kyiv’s EU accession, it was coherent to envisage Ukraine’s NATO accession as the optimal way of defending the country and the entire continent.While the processes of EU and NATO enlargement are at the core of the European security architecture, opinions diverge about France’s priorities regarding the sequence and interconnection between them. Some believe that it is difficult for France to imagine Ukraine joining the EU unless it becomes a NATO member first. For others, France aims to advance both processes simultaneously. Yet others believe that eventually France would be ready to consider Ukraine’s EU accession even if it does not join NATO. Conversely, if the EU enlargement process ran into difficulties, accession to NATO could be instrumental in avoiding a situation where Ukraine would be left in a precarious balance, excluded from both organisations and exposed to enduring threats from Russia.

2.5. A leap forward on Ukraine

Over the course of February and March 2024, Emmanuel Macron picked up the mantle of Ukraine’s firmest ally in Europe, affirming that nothing should be ruled out to defeat Russia, short of entering into war against it. His tough rhetoric has been backed up by the long-term security commitments to Ukraine that France entered into with the Agreement on security cooperation, signed on 16 February 2024. The ink was barely dry on this deal when the French defence minister, Sébastien Lecornu, announced that three French companies planned to manufacture drones and terrestrial equipment on Ukrainian soil.[3]Many capitals, including Berlin and Washington, quickly rejected Emmanuel Macron’s reference to the option of potentially sending allied troops to Ukraine. Yet, by raising this option, the French president positioned his country in the vanguard of the resistance to revisionist Russia.

Awareness of the gravity of the context accounted for Emmanuel Macron’s attempt to introduce ‘strategic ambiguity’ vis-a-vis Russia, a choice he strongly reaffirmed in his Sorbonne speech in April 2024. By the end of 2023, the degree of complacency that had followed the mobilisation of US and EU support for Kyiv, and Ukraine’s successes against Russian forces, had begun to fade away. For one thing, Western support proved to be ‘too little, too late’ to empower Ukraine to carry out a successful counteroffensive. For another, Donald Trump’s scathing attacks on NATO’s allies across the Atlantic made it clear that for Europe the ‘peace dividend’ of the post-Cold War era had ended. The recognition of the magnitude of the threats that a defeat of Ukraine would pose to Europe was at the heart of Emmanuel Macron’s strategic pivot. The French president concluded that what is at stake in Ukraine is Europe itself: its security, the resilience of its democratic systems, its credibility and its future as a political project. Therefore, ensuring that Russia does not win the war of aggression against Ukraine is not solely a moral commitment, but the ‘sine qua non condition’ for preserving European security.

From the French perspective, the response to the Russian threat to Europe, aggravated by the risk of American disengagement from the continent, is to strengthen European sovereignty and strategic autonomy. Emmanuel Macron’s strategic leap forward on Ukraine is part and parcel of his determination to enhance the convergence of European partners around this goal. By the same token, his recent initiatives over Ukraine go hand-in-hand with his efforts to reinforce European defence policy. Russia’s war against Ukraine conferred a new sense of urgency to France’s long-standing calls for the development of a common European defence strategy and stronger defence industry capabilities. Steps have been made to enhance France’s defence industry capacity, in areas such as to ammunition production, but more investment will be needed to match President Macron’s reiterated calls to move to a ‘war economy’ footing. At a time of growing fiscal constraints, this will be a difficult political balancing act for Paris.

Conclusion: new patterns, and obstacles, to leadership

A different Europe is emerging following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with the war having repercussions for the regional security order, national security strategies and Europe’s political landscape. Old alignments have been upset and new ones are emerging. The war is diluting the (ill-conceived) distinction between Old and New Europe and respective strategic cultures. The Franco-German tandem has been the cornerstone of European integration, but it is not a given that it will continue to play this role in future. Mutual frustration over strategic divergences, accentuated by the pressure imposed by the war, is exposing tensions between Paris and Berlin. While under strain, the partnership remains of critical importance to both sides, not least because it provides a basis for wider cooperation formats, as the revival of the Weimar triangle in 2023 demonstrates. However, Paris has clearly pursued a pattern of strategic bilateralism to diversify its partnerships in Europe, both before and after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, such as through the comprehensive treaties signed with Italy in November 2021 and with Spain in January 2023.

Alignments are changing in other parts of Europe too. Central and eastern European countries are far from being on the same page concerning their assessment of the risks posed by Russia and of the requirements to support Ukraine. Budapest espouses an openly Russia-friendly position, the new government in Bratislava is highly sceptical of supporting Ukraine in the war effort, while Warsaw and the Baltics are among Kyiv’s staunchest allies. President Macron’s overtures to the countries of central and eastern Europe have strengthened political ties with the region. The French President appears to have concluded that pursuing a strong and sovereign Europe requires deepening mutual understanding with partners on the continent’s eastern flank.

In this fluid context, the French stance on Russia and Ukraine has shifted progressively, with an acceleration in early 2024. The step change took place when the shifting balance of power on the battleground, together with stalemate in the US Congress regarding assistance to Kyiv, heightened concerns about the capacity of the West to sustain Ukraine. If caution had long framed France’s approach to Russia, since late February, President Macron distinguished himself by ‘thinking out of the box’ and refusing to draw red lines delimiting Western support for Ukraine. If Emmanuel Macron used to speak about a European security order directed at managing Russia, with a view to eventually involving it in the regional architecture, today France’s priority is to build Europe’s collective defence to deter Russia from further aggression.

Ambitious rhetoric has helped Emmanuel Macron score geopolitical points in eastern Europe and raise France’s geopolitical profile in the struggle with Russia, but has not sufficed to avert criticism of France over its military aid to Ukraine. Data from the Kiel Institute show a sharp discrepancy between France’s stated determination to defend Ukraine and its actual contribution in terms of weapons deliveries to Kyiv. Paris has contested these reports, pointing to the fact that it delivered on its commitments in a timely way, through weapons that made a significant difference on the ground, as confirmed by the Ukrainian side. French initiatives in support of Kyiv’s defence go beyond deliveries and maintenance of military equipment and extend to intelligence exchange, training and industrial cooperation. After providing more than €3.8 billion in military aid between February 2022 and December 2023, Paris has pledged to provide up to €3 billion in 2024 and to continue supporting Ukraine for the next ten years, as stipulated in the agreement on security cooperation. Even so, France still lags behind Germany, by far the largest military aid donor to Ukraine in Europe. Alongside military support to Ukraine, France is contributing to the security of eastern Europe in various other ways. For one thing, the consolidation of France’s military presence in Romania, Estonia and Lithuania reflects the willingness to assert France’s role as a security provider in eastern Europe. For another, the defence cooperation pact that Paris signed with Chisinau in early March 2024 demonstrates France’s determination not only to advance an autonomous policy in relation to Moldova, but to protect the country from Russia’s destabilising force.

Overall, the shift in France’s policies towards the eastern flank of Europe is real. It entails a profound reassessment of security threats and geopolitical challenges, and of the answers they require. However, the underlying motivation of this far-reaching change is less novel than grand speeches may suggest. It embodies continuity in France’s long-standing geopolitical thinking about the place of Europe in a volatile world, and the role of France in Europe. Striving for a united and sovereign Europe continues to be at the heart of France’s grand strategy. According to President Macron, only a united Europe can guarantee France’s genuine sovereignty and its ability to defend its values and interests. Europe continues to be seen as a multiplier of France’s power and leading role.

In pursuing the aspiration to build European sovereignty while full-scale warfare rages in Europe, Paris faces three major challenges however. The first is to make this case in a way that not only reflects France’s priorities but also meets the interests of the other member states. Second, if Paris is determined to assert its leadership role, military assistance to Ukraine should match the level of Emmanuel Macron’s ambition. The third challenge lies at home. While differences of nuance persist, the diplomatic and military elite, and most French commentators with expertise in such matters, broadly share the position of the French president. In contrast to the strategic elite however, members of the political sphere find Emmanuel Macron’s posture extremely controversial. As the political campaign ahead of the European elections in June intensifies, opposition parties and rivals from the far right to the far left have vehemently criticised his recent declarations and initiatives. It remains to be seen whether President Macron can position himself at the helm of a united Europe confronting a revisionist Russia if he fails to mobilise domestic support for his European agenda.

- About the author: Teona Giuashvili is former Georgian diplomat and policy fellow at the Florence School of Transnational Governance, European University Institute.

- Source: This article was published by Elcano Royal Institute

[1] The author is grateful to the officials and experts who have generously shared their views and experience through anonymised interviews conducted between October and December 2023. This paper builds on their insights.

[2] In 2008, French President Nicolas Sarkozy together with German Chancellor Angela Merkel led the opposition to the American initiative to grant Georgia and Ukraine the NATO Membership Action Plan (MAP). On this topic, see Sylvie Kauffmann (2023), Les Aveuglées Comment Berlin et Paris ont laissé la voie libre à la Russie, Stock, pp.63-95.

[3] Furthermore, Sébastien Lecornu announced that France would deliver hundreds of old armoured vehicles and 30 Aster missiles to Ukraine in 2024 and early 2025, as part of a new aid package. See M. Cabirol, R. Jules and L. Vigogne, “Sébastien Lecornu: J’exige la constitution de stocks pour produire des munitions”, La Tribune Dimanche, 31 March 2024.

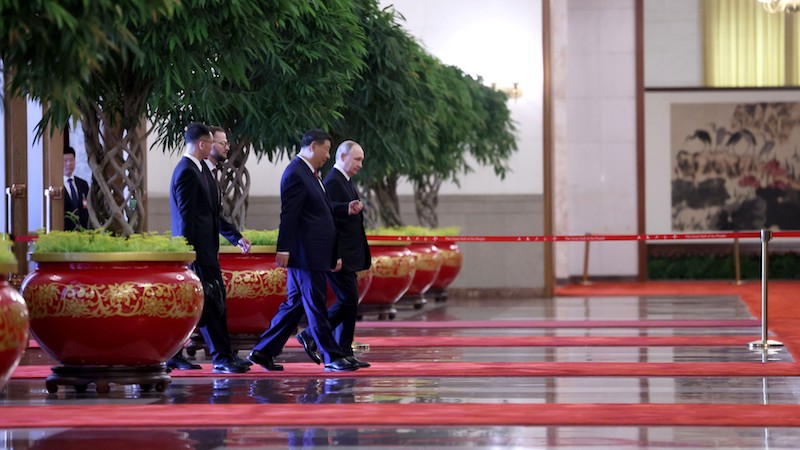

The state visit by Russian President Vladimir Putin to China underscored that the two superpowers’ choice of entente-type alignment has gained traction. It falls short of explicit military obligations of support and yet will not entirely rule out military support either. By embracing a form of strategic ambiguity, it provides them the optimal means to address the common threat they face from the United States via the prism of collective action while preserving the autonomy for independent action to pursue specific interests.

The epochal significance of the talks in Beijing lies in that the bedrock of strategic understanding accruing steadily to the modelling effort of the Russia-China entente has evolved into a more effective alignment choice than a formal alliance to balance against the US’ dual containment strategy.

The entente permits both Russia and China to strike the middle ground between entrapment and deterrence. At the same time, the strategic ambiguity inherent in these two seemingly self-contradictory goals of an entente is expected to be a key component of its success as an alignment strategy.

The Russian state news agency Tass reported from Beijing on Thursday that “the central topic is expected to be the Ukraine crisis and the informal tea party and a dinner in the restricted format between Xi and Putin would be “the most important part of the Beijing talks” where the two presidents would hold “substantial talks on Ukraine.”

In his media statement following the talks, Xi Jinping made clear the guiding principle. He said, “The idea of friendship has become deeply ingrained in our mindsets… We also demonstrate mutual and resolute support on matters dealing with the core interests of both parties and address each other’s current concerns. This is the main pillar of the Russia-China comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation for a new era.”

Xi added, “China and Russia believe that the Ukraine crisis must be resolved by political means… This approach aims to shape a new balanced, effective and sustainable security architecture.”

Putin responded that Moscow positively evaluates the Chinese plan. He told Xinhua news agency in aaa interview that Beijing is well aware of the root causes and global geopolitical significance of this conflict. And the ideas and proposals recorded in the document testify to the “sincere desire of our Chinese friends to help stabilise the situation,” Putin said.

The mutual trust and confidence is such that the current Russian offensive in Kharkov began on May 10 just six days before Putin’s trip to China. Beijing knows it is a defining moment in the war — Moscow is only 3-4 minutes away in a missile strike if NATO gains access to the city.

Notably, the joint statement issued after Putin’s visit affirms that for “a sustainable settlement of the Ukrainian crisis, it is necessary to eliminate its root causes.” Going beyond the vexed issue of NATO expansion, the 7000-word document for the first time attacked the demolition of monuments to the Red Army in Ukraine and across Europe and the rehabilitation of fascism.

Beijing senses that Russia has gained the upper hand in the war. Indeed, if the NATO were to suffer defeat in Ukraine, it would have profound consequences for the transatlantic system and the US’ inclination to risk yet another confrontation in the Asia-Pacific. (Interestingly, Taiwan’s outgoing foreign minister, Joseph Wu, said in an interview with Associated Press that Putin’s visit to China testified to Russia and China “helping each other expand their territorial reach”.)

China is mindful of the fault lines in the Euro-Atlantic alliance and is purposively developing close relationship with parts of continental Europe. This was the leitmotif of Xi’s recent tour of France, Serbia and Hungary, as evident from the nervous reaction in Washington and London.

China hopes to buy as much time as possible to keep the flashpoint in Taiwan at bay. China has no illusions that its confrontation with the US is strategic in nature and at its core lies Washington’s aim to control access to the world’s resources and markets and impose the global standards in the fourth industrial revolution.

Unlike Russia, China carries no baggage in its relations with Europe. And European priorities do not lie in getting entangled in a US-China confrontation, either. European elites are not considering any new policy yet but this is likely to change after the elections to the European Parliament (June 6-8) as they are pushed to find a compromise with Russia stemming out of the rising economic costs associated with defence spending, deepening concern about the prospect of a direct conflict with Russia amidst the growing realisation that Russia cannot be defeated, and an awakening of public opinion that European spending on Ukraine in effect is financing the US military-industrial complex.

China expects all this to have a salutary effect on international security in a near term. The bottom line is that China has high stakes in a harmonious relationship with Europe, which is a crucial economic partner, second only to ASEAN. As a Russian pundit wrote last week, “China sincerely believes that economics play a central role in world politics. Despite its ancient roots, Chinese foreign policy culture is also a product of Marxist thinking, in which the economic base is vital in relation to the political superstructure.”

Simply put, Beijing is counting that the deepening of its economic ties with the EU is the surest way to encourage the leading European powers to rein in the US’ adventurist, unilateral interventionist strategies in world politics.

The dialectics at work in the Sino-Russian entente cannot be properly understood if the western narratives keep counting the trees but only to miss the big picture of the lumber timber woodland. By the way, one factor in the successful “de-dollarisation” of the Russian-Chinese payment system is that the US has lost its wherewithal to monitor the traffic across that vast 4,209.3 km border and is increasingly kept guessing what’s going on.

Time is on Russia and China’s side. The gravitas in their alliance is already infectious, as far-flung countries in the global south flock to them. A strong Russian presence along west Africa’s Atlantic coast is now only a matter of time. The intensifying foreign policy coordination between Moscow and Beijing means that they are moving in tandem while also pursuing independent foreign policies and allowing space for them to leverage specific interests.

Xi stated in his media statement that China and Russia are committed to strategic coordination as an underpinning of relations, and steer global governance in the right direction. On this part, Putin highlighted that the two big powers have maintained close coordination on the international stage and are jointly committed to promoting the establishment of a more democratic multipolar world order.

The symbolic component of Putin’s visit to China, being his first trip after the inauguration, is of great importance. The Chinese read all these signs perfectly and fully appreciate that Putin is sending a message to the world about his priorities and the strength of his personal ties with Xi.

The joint statement, which signifies a deepening of the strategic relationship, mentions plans to step up military ties and how defence sector cooperation between the two nations has improved regional and global security.

Most important, it singled out the United States for criticism. The joint statement says, “The United States still thinks in terms of the Cold War and is guided by the logic of bloc confrontation, putting the security of ‘narrow groups’ above regional security and stability, which creates a security threat for all countries in the region. The US must abandon this behaviour.”

The joint statement also “condemn(ed) the initiatives on confiscation of assets and property of foreign states and emphasise(d) the right of such states to apply retaliation measures in accordance with international legal norms” — a clear reference to Western moves to redirect profits from frozen Russian assets or the assets themselves, to help Ukraine. China is on guard, as evident from its steady downsizing of holdings of US Treasury bonds and addition of more and more gold to its reserves than it had in nearly 50 years.

- This article was published at Indian Punchline