Day: April 25, 2024

NPR News: 04-25-2024 9PM EDT

ESG Puppeteers – OpEd

By Paul Mueller

The Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) framework allows a small group of corporate executives, financiers, government officials, and other elites, the ESG “puppeteers,” to force everyone to serve their interests. The policies they want to impose on society — renewable energy mandates, DEI programs, restricting emissions, or costly regulatory and compliance disclosures — increase everyone’s cost of living. But the puppeteers do not worry about that since they stand to gain financially from the “climate transition.”

Consider Mark Carney. After a successful career on Wall Street, he was a governor at two different central banks. Now he serves as the UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance for the United Nations, which means it is his job to persuade, cajole, or bully large financial institutions to sign onto the net-zero agenda.

But Carney also has a position at one of the biggest investment firms pushing the energy transition agenda: Brookfield Asset Management. He has little reason to be concerned about the unintended consequences of his climate agenda, such as higher energy and food prices. Nor will he feel the burden his agenda imposes on hundreds of millions of people around the world.

And he is certainly not the only one. Al Gore, John Kerry, Klaus Schwab, Larry Fink, and thousands of other leaders on ESG and climate activism will weather higher prices just fine. There would be little to object to if these folks merely invested their own resources, and the resources of voluntary investors, in their climate agenda projects. But instead, they use other people’s resources, usually without their knowledge or consent, to advance their personal goals.

Even worse, they regularly use government coercion to push their agenda, which — incidentally? — redounds to their economic benefit. Brookfield Asset Management, where Mark Carney runs his own $5 billion climate fund, invests in renewable energy and climate transition projects, the demand for which is largely driven by government mandates.

For example, the National Conference of State Legislatures has long advocated “Renewable Portfolio Standards” that require state utilities to generate a certain percentage of electricity from renewable sources. The Clean Energy States Alliance tracks which states have committed to moving to 100 percent renewable energy, currently 23 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. And then there are thousands of “State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency.”

Behemoth hedge fund and asset manager BlackRock announced that it is acquiring a large infrastructure company, as a chance to participate in climate transition and benefit its clients financially. BlackRock leadership expects government-fueled demand for their projects, and billions of taxpayer dollars to fund the infrastructure necessary for the “climate transition.”

CEO Larry Fink has admitted, “We believe the expansion of both physical and digital infrastructure will continue to accelerate, as governments prioritize self-sufficiency and security through increased domestic industrial capacity, energy independence, and onshoring or near-shoring of critical sectors. Policymakers are only just beginning to implement once-in-a-generation financial incentives for new infrastructure technologies and projects.” [Emphasis added.]

Carney, Fink, and other climate financiers are not capitalists. They are corporatists who think the government should direct private industry. They want to work with government officials to benefit themselves and hamstring their competition. Capitalists engage in private voluntary association and exchange. They compete with other capitalists in the marketplace for consumer dollars. Success or failure falls squarely on their shoulders and the shoulders of their investors. They are subject to the desires of consumers and are rewarded for making their customers’ lives better.

Corporatists, on the other hand, are like puppeteers. Their donations influence government officials, and, in return, their funding comes out of coerced tax dollars, not voluntary exchange. Their success arises not from improving customers’ lives, but from manipulating the system. They put on a show of creating value rather than really creating value for people. In corporatism, the “public” goals of corporations matter more than the wellbeing of citizens.

But the corporatist ESG advocates are facing serious backlash too. The Texas Permanent School Fund withdrew $8.5 billion from Blackrock last week. They join almost a dozen state pensions that have withdrawn money from Blackrock management over the past few years. And last week Alabama passed legislation defunding public DEI programs. They follow in the footsteps of Florida, Texas, North Carolina, Utah, Tennessee, and others.

State attorneys general have been applying significant pressure on companies that signed on to the “net zero” pledges championed by Carney, Fink, and other ESG advocates. JPMorgan and State Street both withdrew from Climate Action 100+ in February. Major insurance companies started withdrawing from the Net-Zero Insurance Alliance in 2023.

Still, most Americans either don’t know much about ESG and its potential negative consequences on their lives or, worse, actually favor letting ESG distort the market. This must change. It’s time the ESG puppeteers found out that the “puppets” have ideas, goals, and plans of their own. Investors, taxpayers, and voters should not be manipulated and used to climate activists’ ends.

They must keep pulling back on the strings or, better yet, cut them altogether.

- About the author: Paul Mueller is a Senior Research Fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research. He received his PhD in economics from George Mason University. Previously, Dr. Mueller taught at The King’s College in New York City.

- Source: This article was published by AIER

By Octavio Bermudez

Javier Milei’s administration is generating much deserved commentary, both positive and negative. Critical discussion is vital since he is the first libertarian president, so keeping a distance between libertarianism itself and his government actions is a must if libertarians don’t want to fall with him should his government plans fail.

Just because he is a libertarian and has accessed the presidency doesn’t mean he has immanent support from the rest of the libertarian movement. Thus, it would not be wise to jump into his -short term- winning wagon. Staying in a critical stance until further results are shown is the better way.

A great question among libertarian and non-libertarian social settings has been rolling around since Milei kicked off as an outsider and gained vast popularity. The question is: Is he causng a revolution of liberty in Argentina? Meaning, has the Argentine population gravitated towards the free market and away from statism? It is surely a hard question to answer, in this article we will approach an answer.

Recent polls suggest that even with the recession, Milei keeps a high positive image among the population. In congress he has had no success yet but with the executive tools at his hand he has been making both real and symbolic changes in policy. From assuring that currency inflation will cease to selling state owned planes and vehicles (and much more). Both the real and symbolic changes have had an impact in the public opinion, he has kept his promise of reducing the state apparatus.

Interestingly, the best analysis of the Milei phenomenon has not come from his own supporters but from detractors. That analysis is the one made by sociologist Pablo Seman and Nicolás Welschinger. The authors point to many reasons why the public landscape has changed since Milei entered the political arena. Their analysis is also self-critical since they admit many failures by the progressive politicians and institutions.

The progressive voter seemed to be willing to sacrifice efficiency for public ownership, in the sense that it didn’t matter if the institution was inefficient, if it was state owned then everything was fine. This kind of dogmatism seemed unbreakable since it appeared to withstand any calamity produced by the state institutions in their inefficiency. Yet, the apparent dogmatism was not as indestructible as it looked. Progressivism took its supporters to such an extreme level of economic downfall that the support of its institutions was not dogmatic anymore but based on experience.

This downfall of the progressive discourse generated frustrations and shattered dreams which Milei was able to capture. He named the perpetrators of the Argentine disaster, calling them “casta” (caste) and explained in detail how the state institutions had come to the present situation. Milei brought hope to these disillusioned voters who did not necessarily identify with him but saw coherence and reality in his discourse. The “estado presente” (the Argentinian version of the welfare state) has transformed from a positive right to a suffering circumstance. Its defense is even more difficult than before. Progressives are reduced more and more to their dogmatic circles.

Milei’s supporters -as Selman and Welschinger explain- are gathered in three consecutive rings, feeding the forces of discontent for the “caste” from the circle within to the outwards circles. The first circle is the “market fundamentalists” one, ideologues, acquainted with far right and libertarian doctrine, they create the symbols that are perceived by the second and third ring of voters that begin to brace Milei in different stages of the electoral race.

Milei’s rise comes as the connection between the progressive elites and the people erodes to an extreme that the statist discourse seems to be coming from another dimension. The egalitarian realities that it allegedly leads degenerate and end up as parodies of themselves.

There is a demand for a framework that allows for individual effort to bring about prosperity. The individualism of much of the Argentine population comes to bear here, they see the path towards stability and success in individual hard work. Sacrifice is what brings about achievements for this part of the populace, they demand not gifts but opportunities. Milei was able to represent these sentiments by making a difference between “la gente de bien” (people of good) and “la casta” (the caste). The caste is portrayed as parasitic public actors that live off as leechers of the people of good. The caste only aims for survival of its own situation which is the status quo. Milei comes to expose them.

Some political analysts have expressed their concern about Milei’s plan to overturn the status quo. If the wellbeing of the nation must be sacrificed to keep the political system “orderly” then it must be done, since they argue that broken political systems are hard to reconstruct. This argument is not only far from well-meaning and caring for the suffering of the people, but it fails in its portrayal of Milei. He doesn’t come to destroy but to reorganize. As he himself has said, one of his political aims is to reorder the political theater into ideological parts. So, the collectivist voters vote for collectivist parties and free market supporters vote for free market parties. That’s the logic of Milei’s plan that for now seems to have achieved some results.

The powers of the status quo have disconnected themselves from the public, they do not represent “the people” anymore but only their own interests. Thus, outside voices are held in higher stem than they would in normal circumstances. Milei comes to be that outside voice. It dignifies his supporters by acknowledging them as individuals that can change their future from the decadence decreed by “the caste”.

Above his results once in office, Milei has achieved a communicational victory. Making free market thinking as popular as it ever was. This doesn’t mean that people are suddenly libertarians, but the “Zeitgeist” has veered away from collectivism. This change in direction must be sustained and capitalized if a long-term victory is to be held. If not, then Milei’s moment will pass to history as one more “free marketer” adventure.

- About the author: Octavio Bermudez is an Argentinian student of Political Sciences and International Relations at the University of Palermo, Argentina. On top of his academic studies on political science and IR theory, his main areas of interest and research are philosophy (with a focus on political philosophy), economics and history.

- Source: This article was published by the Mises Institute

Since Russian President Vladimir Putin launched his expanded war against Ukraine, it has been commonplace to predict the outcome depending on shifts in the frontlines. Many predict a Russian victory when Russian forces advance and a Ukrainian triumph when Ukrainian units press forward.

Neither Russia nor Ukraine, however, will win or lose the war based solely on what happens at the front. Instead, both have sought to come out on top by bringing the war home to the other through attacks on population centers far beyond the lines. Frequent Russian bombing raids on Ukrainian cities and increased Ukrainian drone attacks on Russia’s border regions and large city centers, including St. Petersburg, Moscow, and Kazan, have attracted more attention in recent months (see EDM, December 21, 2023, April 11, 18, 24).

Far less attention, however, has been paid to another development that may prove fateful: Kyiv’s impressive organization of a partisan movement in the Russian-occupied portions of Ukraine and its support of ethnic and regional movements within the Russian Federation (see EDM, May 16, July 25, 2023, January 25, February 1). Moscow had largely failed to respond to these efforts until very recently, and these actions are increasingly raising the specter of disintegration in Russia.

The successes of Ukraine’s partisan movement over the past year have led some in Moscow to recall that it took the Soviet government more than a decade after World War II to suppress Ukrainian partisans. They have also raised fears that, if Russian forces were able to occupy large swaths of Ukraine, Moscow would face a similar and perhaps even greater challenge not only in Ukraine but among non-Russians and regional groups within an expanded Russian Empire. The organization of sleeper cells in Ukrainian areas that Russian troops appear to be on the verge of occupying has further enflamed these concerns (Lenta.ru, April 17).

In such circumstances, Putin’s war in Ukraine would not lead to the restoration of some version of the Soviet Union. Instead, it would likely set the stage for a far more violent collapse of that new entity into a plethora of states—possibly becoming what many in the West feared 30 years ago, “a Yugoslavia with nukes.” (For a thoughtful and early warning of such possibilities, see senior Moscow commentator Aleksandr Tsipko’s article on the eve of Putin’s invasion, Mk.ru, May 1, 2022; compare with Window on Eurasia, March 27, 2022, February 28.)

The Ukrainian partisan movement has largely flown under the radar of most because it is impossible to say exactly how large it is—estimates range up to 100,000. It is perhaps even more difficult to specify what actions the movement, rather than regular Ukrainian army units, are independently carrying out. It is clear that Kyiv placed great hopes on partisan operations even before Putin launched his expanded invasion (Ura.news, March 11, 2022). The partisan groups that have emerged in the months since have regularly destroyed Russian infrastructure, killed Russian commanders and political figures, and provided key intelligence to Kyiv about the locations and plans of Russian forces (see EDM, May 16, July 25, 2023). (For a detailed but far from comprehensive listing of these activities, see the chronology in the Kyiv Post, especially December 21, 2023.)

Two other signs point to the Ukrainian partisan groups being large and effective. On the one hand, Russian military officials have acknowledged that they have deployed 35,000 soldiers to combat partisans. This figure is undoubtedly too low but shows Moscow is taking them seriously (Kyiv Post, January 8). On the other hand, Russia, after earlier dismissing any role for partisans in the current war, is now organizing its own pro-Moscow partisan groups in Ukraine, even claiming successes for them (Vzglyad, June 29, 2023). This sets the stage for a war in the shadows between the partisans of both countries (Donetskmedia.ru, April 15; Segodnia.ru, April 21).

Yet another reason explains why Moscow is now taking the Ukrainian partisans more seriously: The Kremlin sees their partisan activity as something that has crossed into Russia and become an even more immediate threat to the Putin regime. The attacks have focused on draft centers and, more recently, on industries critical to the war effort and have utilized the rising tide of weapons now in private hands in Russia since the start of the war (see EDM, May 17, 2022;TASS, January 22).

In part, the Kremlin is simply accepting its own propaganda as true. The recent attack on Crocus City Hall in Moscow highlighted that the Kremlin has tried to link all actions against itself to Ukraine—both to mobilize the population against such actions and to be in a position to impose harsher penalties on those who engage in them (Novaya Gazeta Europe, April 2). Perhaps far more consequential, these concerns reflect Russian wariness that Ukraine is now using military means, including partisans, to promote the disintegration of the Russian Federation itself.

Kyiv has infuriated Moscow by reaching out to non-Russian and regional groups inside Russia, backing their aspirations for independence, training such people, and even labeling Putin’s Russia an “evil empire” (see EDMOctober 13, 2022, January 18, 2023, January 25; Window on Eurasia, December 25, 2023). Moscow’s alarm has certainly intensified further after Roman Svitan, a Kyiv military commentator, said on April 20 that Ukraine is targeting places in Russia with an eye to promoting the country’s disintegration—something that would likely require Ukrainian-trained partisans to succeed (24tv.ua, April 20). Moscow has responded with more repression at home and a greater focus on partisans in Ukraine than ever before.

Ukrainian partisans, despite all the success against Russian forces, will not win the war for Kyiv on their own (Al Jazeera, September 6, 2022). Their actions inside Ukraine, however, suggest that they are playing a far more important role there and inside Russia. (For a useful discussion of these possibilities and how they are shaping Moscow’s thinking, see Irregular Warfare Center, September 21, 2023.) At the very least, the successes of Ukraine’s partisans and Moscow’s decision to counter by setting up its own partisan detachments deserve far more attention and the Ukrainian effort far more support from those who want to see Putin’s aggression stopped.

- This article was published at The Jamestown Foundation’s Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 64

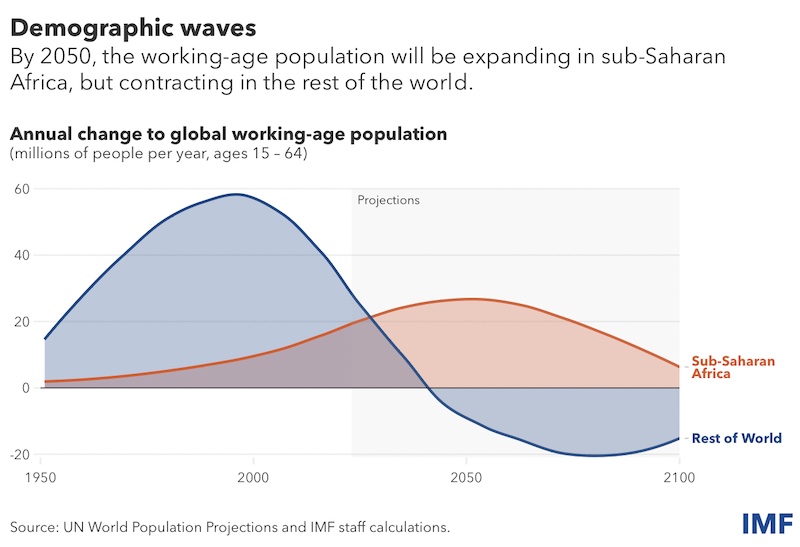

Demographic transition may be the biggest single opportunity for the economies of sub-Saharan Africa, but countries will only be able to enjoy the dividends if they make sufficient investment in education.

The region’s population is poised to double to 2 billion by 2050. As the Chart of the Week (see below) shows, that expansion will be led by growth in the working-age population of those ages 15 to 64 that will outpace other age groups and drive almost all the increase.

Sub-Saharan Africa has made notable progress in expanding access to schools in recent decades, but outcomes in the region still trail those in other emerging market and developing economies, as we explore in our latest Regional Economic Outlook.

Nearly three in 10 school-age children do not attend school. For primary school students, the completion rate is around 65 percent, compared with a world average of 87 percent. And the literacy rate for those ages 15 to 24 is only 75 percent, below the nearly 90 percent rate in other emerging market and developing economies. On top of this, pandemic-related school closures led to learning losses that in some cases reversed years of progress.

One reason for these shortfalls is that government spending on education in sub-Saharan Africa falls short of international benchmarks in several countries. The median education budget was equal to about 3.5 percent of gross domestic product in 2020, which is below the international recommendation of at least 4 percent of GDP. But recent IMF analysis reveals that achieving the key Sustainable Development Goal of universal primary and secondary school enrollment by 2030 may require doubling education expenditures as a share of GDP, including from both public and private funding sources.

Greater spending to improve access is important, but equally important is the effort to ensure that funds are efficiently used. Indeed, for the median country in sub-Saharan Africa, only 15 percent of students in primary and secondary school achieve more than the minimum learning outcome, while teacher training rates have fallen steadily for two decades.

Investment in education provides clear long-term economic gains that more than justify the cost. Greater government spending on education offers economic benefits such as higher productivity and foreign direct investment, as shown in the latest Fiscal Monitor. Governments in sub-Saharan Africa should protect education budgets amid tighter fiscal constraints and the ongoing funding squeeze, and implement best practices in public financial management on raising domestic revenue and ensuring that funds are well-spent.

For their part, donors and international organizations should maintain or expand education funding support across the region. This will ensure the supply of a productive labor force that will be needed more and more urgently by a rapidly aging world, and help the region become one of the world’s most dynamic sources of new demand for consumption and investment.

More broadly, it is critical to better connect the region’s abundant human resources with the abundant capital in advanced economies and major emerging markets. With the right kind of policies—especially in education—we could see sub-Saharan Africa attracting long-term flows of investment, technology, and know-how. And, given rapidly evolving technology and the landscape for jobs, this could unlock the full potential of the region’s young people, better equipping them for the future.

—This article is based on the April 2024 Regional Economic Outlook for sub-Saharan Africa. For more on the region’s demographic transformation, see African Century in the September 2023 issue of Finance & Development magazine.

About the authors:

- Michele Fornino is an Economist in the IMF’s African Department, where he collaborates on the production of the Regional Economic Outlook and on the Mali desk. Prior to his current assignment, he worked in the Statistics Department of the IMF and participated to AIV consultations in Luxembourg and Kiribati.

- Andrew Tiffin is a senior economist in the Regional Studies Division of the IMF’s African Department. In his time at the IMF, Andrew has worked on a range of countries including Ukraine, Russia, Romania, Italy, Lebanon, and Jordan. He has worked extensively on the IMF’s risk-assessment process and other policy issues, and has a current interest in the application of modern statistical techniques (machine learning) to the analysis of the Fund.

Source: This article was published by IMF Blog

By Marina Yue Zhang, Mark Dodgson and David Gann

The technological race between the United States and China is a defining narrative of our times. The contest, far more than a mere rivalry over technological supremacy, encapsulates the shifting of economic power, national security imperatives and soft power that will shape the new world order.

Humanity has witnessed three industrial revolutions, each of which has positioned its epicentre as the economic hub of its era. As the third revolution draws to a close, the seeds of a new wave are being sown. The nation that emerges as the centre of this forthcoming technological revolution will become the economic nucleus of the coming new age. The rapid rise of China’s scientific and technological power is seen as a threat to the United States’ supremacy in the new technological revolution.

Against this backdrop, there have been escalating levels of techno-nationalism, characterised by nations prioritising the development and protection of domestic technological capacities over purely economic considerations. This focus extends to an arms race in industrial policiesand technology sovereignty.

The rise of China as a technological powerhouse and its assertive recalibration of its international standing have raised concerns about China’s potential threat to the existing world order. From Washington’s perspective, China’s technological advancements not only strengthen a strategic competitor, but also potentially enhance its military capabilities, threatening US national security.

Accordingly, the United States has implemented technology sanctions and export controls in select areas such as advanced semiconductors, and has introduced policies to protect its domestic manufacturing capability. These policies are viewed as protective measures against China’s technological ascendance. But China sees these actions as attempts to impede its development and has initiated retaliatory measures such as export controls on critical metals and rare earth separation technologies.

The disparity in perspectives on the US–China tech rivalry has transformed their previously symbiotic relationship into a tug-of-war within a techno-nationalist race. This risks not only segregating supply chains, but also decoupling technology. The danger lies in the United States’ reluctance to be surpassed by China, just as China is unlikely to relinquish its aspirations for growth. The stakes of the US–China tech rivalry are incredibly high, with the potential to reshape the broader geopolitical landscape.

To mitigate the drawbacks of techno-nationalism and prevent technological decoupling, more refined policies are necessary. It is essential to fight the right technology battles, as different technologies have varying applications and geopolitical implications.

Navigating the technological battleground necessitates strategies tailored to different technological domains. It is crucial to safeguard technologies that could enhance the strategic or military advantages of an adversary. It is equally important to seek areas of complementarity and cooperation, especially in tackling global challenges. The strategic decisions made by each country today will not only shape the trajectory of US–China relations but will also profoundly influence the international community’s approach to technology, security and diplomacy for decades to come.

General-purpose technologies, such as semiconductors and artificial intelligence, necessitate more defensive policies due to their potential military and security impacts as well as their sometimes unpredictable consequences. Yet in areas critical to sustainable development — including renewable energy, public health and basic scientific research — global collaboration should take precedence over competition.

Policymaking should be based on comprehensive evaluations of the nature of technological development and the sustainable competitive advantages that can be derived from innovative technologies. Identifying current and future competitive advantages should draw upon well-established technology assessment toolkits.

Technological decoupling between the United States and China is not inevitable, nor should it be. Rapid technological development underscores the importance of international cooperation in addressing global challenges where both countries share common interests. Both nations should maintain domestic policies that protect their core national interests while also demonstrating flexibility in cooperation.

This requires shifting from constraints to enablement, leveraging competitive advantages in technology development and use. These advantages include the synergy between industry and science, the development of technology infrastructure accessible to smaller countries and the sharing of data and pooling of a skilled and diverse workforce. Effective governance mechanisms are essential for transforming ideas into innovation. Investing in these areas will yield broader benefits than sanctions and punitive tariffs.

Australia stands at a strategic crossroads given its significant links with both the United States and China. The suggestion that Australia should rely on its participation in international coalitions of democracies as a response to China’s technological rise may be overly simplistic and unpragmatic.

The reality is that Australia maintains close scientific ties with both the United States and China. Should the US–China tech race escalate to technological decoupling, Australia, as an ally of the United States, may face pressure to curtail its engagements with China. Such a scenario could adversely affect Australia’s progress on research and development.

To safeguard its national security and economic interests, Australia must adopt flexible and prudent diplomatic strategies, pursue an independent industrial policy and actively contribute to multilateral frameworks. Initiatives could also include organising forums to delineate technologies requiring protection and identifying areas for complementarity and cooperation.

Given its position as a credible third-party country, Australia is uniquely placed to lead such efforts. This approach should be underpinned by policies guided by a clear-eyed assessment of Australia’s national interests, values, competitive positions and the nature of technological battlefields.

About the authors:

- Marina Yue Zhang is Associate Professor at the Australia–China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney.

- Mark Dodgson is Emeritus Professor at the University of Queensland and Innovator in Residence at the University of Oxford.

- David Gann is Professor of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Said Business School, University of Oxford and Chairman, UK Industrial Fusion Solutions.

Source: This article was published by East Asia Forum