New Armenian literary publications

New Armenian literary publicationsThe International Armenian Literary Alliance announced five new literary publications by Armenian authors, including Armen Davoudian’s “The Palace of Forty Pillars,” Leila Boukarim’s “Lost Words,” illustrated by Sona Avedikian, Tenny Minassian’s “Lucy Goes to The Gentle Barn,” illustrated by Agavny Vardanyan, stories about immigrant life in Little Armenia by Naira Kuzmich, and Manoug Hagopian’s “Life in the Armenian Community of Aleppo.”

Davoudian’s “The Palace of Forty Pillars” is a Publishers Weekly and The Rumpus’ most anticipated poetry book of 2024. According to poet Richie Hofmann, the book is “brilliant and deft and heartfelt.”

“In this formally radical debut, Armen Davoudian shows how rhyme enacts longing for a homeland left behind; how meter sings to a lost beloved; and how a combination of the two can map a self—or idea of the self—relinquished so that a new life, and all the happiness it deserves, can take shape,” said poet Paul Tran.

“Palace of Forty Pillars” book cover

“Palace of Forty Pillars” book cover

Author Armen Davoudian. Photo credit: Matthew Lansburgh

Author Armen Davoudian. Photo credit: Matthew Lansburgh

Wry, tender, and formally innovative, Davoudian’s debut poetry collection, “The Palace of Forty Pillars,” tells the story of a self estranged from the world around him as a gay adolescent, an Armenian in Iran, and an immigrant in America. It is a story darkened by the long shadow of global tragedies—the Armenian genocide, war in the Middle East, the specter of homophobia. With masterful attention to rhyme and meter, these poems also carefully witness the most intimate encounters: the awkward distance between mother and son getting ready in the morning, the delicate balance of power between lovers, a tense exchange with the morality police in Iran.

In Isfahan, Iran, the eponymous palace has only twenty pillars—but, reflected in its courtyard pool, they become forty. This is the gamble of Davoudian’s magical, ruminative poems: to recreate, in art’s reflection, a home for the speaker, who is unable to return to it in life.

Davoudian has an MFA from Johns Hopkins University and is a PhD candidate in English at Stanford University. His poems and translations from Persian appear in Poetry magazine, the Hopkins Review, the Yale Review, and elsewhere. His chapbook, “Swan Song,” won the Frost Place Competition. Armen grew up in Isfahan, Iran, and lives in Berkeley, California.

You can now pre-order “The Palace of Forty Pillars” (to be published on March 19, 2024) from the IALA Bookstore powered by Bookshop. Keep an eye on IALA’s website and socials for their second annual Literary Lights reading featuring Davoudian in 2024.

Leila Boukarim new picture book “Lost Words,” illustrated by Sona Avedikian, tells an Armenian story of survival and hope.

“Lost Words” book cover

“Lost Words” book cover

“It is difficult to find the words to describe the type of loss a Genocide can cause to a young child. I’ve been looking for something similar for my own son. This picture book is a good start to help explain loss and raise the many questions necessary to start the conversation,” said Serj Tankian, activist, artist, and lead vocalist for System of a Down.

Based on a true family story, this inspiring picture book about the Armenian Genocide shares an often-overlooked history and honors the resilience of the Armenian people.

What is it like to walk away from your home? To leave behind everything and everyone you’ve ever known? Poetic, sensitive, and based on a true family history, “Lost Words: An Armenian Story of Survival and Hope” follows a young Armenian boy from the day he sets out to find refuge to the day he finally finds the courage to share his story.

Boukarim writes stories for children that inspire empathy and encourage meaningful discussions. She enjoys reading (multiple books at a time), embroidering, nature walking, and spending time with people, listening to their stories and sharing her own. Boukarim lives in Berlin, Germany.

Author Leila Boukarim

Author Leila Boukarim

Illustrator Sona Avedikian

Illustrator Sona Avedikian

Avedikian is an Armenian illustrator born in Beirut, Lebanon, and currently based in Detroit, Michigan. She loves creating vibrant work and often takes inspiration from Armenian art and architecture.

You can now pre-order “Lost Words” (to be published on March 26, 2024) from the IALA Bookstore powered by Bookshop. Keep an eye on IALA’s website and socials for their second annual Literary Lights reading featuring Leila Boukarim in conversation with Astrid Kamalyan in 2024.

Illustrated by Agavny Vardanyan, Tenny Minassian’s “Lucy Goes to The Gentle Barn,” based on a true story, follows Lucy, a rescue poodle-mix, as she goes on another adventure with her mom. This time they visit an animal sanctuary called The Gentle Barn.

“The Gentle Barn is a special place that not only rescues animals, but allows humans to heal by bonding with them. There is nothing more healing than hugging a cow,” said Tenny Minassian. “I wanted to share the story of our visit to The Gentle Barn because Lucy also rescued me. She saved my life when I was battling depression. I want children to know that even if we are different from each other, whether we are talking about humans or non-human animals, we can still be good friends.”

“Lucy Goes to The Gentle Barn” book cover

“Lucy Goes to The Gentle Barn” book cover

In 2015, a small poodle named Spring, was rescued from a shelter when she was pregnant with four puppies. Lucy was one of those puppies. Shortly after, she became an Emotional Support Animal (ESA) when her mom was struggling with her mental health. They saved each other!

Minassian is a vegan lifestyle coach, business consultant, and independent author living in Los Angeles, California with her Emotional Support Animal Lucy. She focuses on compassionate coaching and donates a portion of proceeds to nonprofit organizations helping animals, people, and the planet. She is an Armenian-American immigrant and came to the U.S. from Iran as a refugee with her family. Visit the website and follow on social media @VeganCoachTenny for more information on upcoming projects and events. Follow Lucy’s fun adventures on her Instagram account.

Vardanyan is an Armenian American character designer and prop artist based in Los Angeles, California. She’s a 2021 Summa Cum Laude graduate from Cal State Northridge with a BA in arts and concentration in animation. In addition to having recently worked as a full-time prop artist for HBO Max’s Fired on Mars, she’s also worked as a children’s book illustrator for GarTam Books and as print designer for New York Times and Indie Bestseller Allison Saft. She is currently working on her first graphic novel, “The Pomegranate Princess.” Learn more about Vardanyan here.

Author Tenny Minassian

Author Tenny Minassian

Illustrator Agavny Vardanyan

Illustrator Agavny Vardanyan

You can now purchase “Lucy Goes to The Gentle Barn” from the IALA Bookstore powered by Bookshop or Abril Bookstore. Part of the proceeds of this book will benefit The Gentle Barn, a national nonprofit with locations in Santa Clarita, CA, St. Louis, Missouri and Nashville, Tennessee.

Naira Kuzmich’s “In Everything I See Your Hand” will capture your heart with 10 brilliant stories about immigrant life in Little Armenia.

“Her writing was rich with Armenian culture, with old blood and the glittering black eyes of strong and deeply feminine women. . . . Since her passing in the fall of 2017, Naira’s talent has inspired me to tell her story to others. She’s caught the fears of many a stalled writer. ‘Here’s the issue,’ she wrote to me. ‘My window is closing.’ In every writer I’ve encouraged to finish their novel, their memoir, their history, I see her hand,” said Roz Foster, Naira’s former literary agent.

What’s the difference between leaving the motherland and leaving the literal mother? When does the journey toward self-possession become something closer to self-exile? Living daily in the tension between assimilation, disillusionment, and desire, the Armenian-American protagonists of “In Everything I See Your Hand” struggle with the belief that their futures are already decided, futures that can only be escaped through death or departure—if they can be escaped at all.

“In Everything I See Your Hand” book cover

“In Everything I See Your Hand” book cover

Naira Kuzmich

Naira Kuzmich

In these ten brilliant stories, Kuzmich spins variations of immigrant life in the Little Armenia neighborhood of Los Angeles. Kuzmich finished this collection before her death at age twenty-nine. Melding empathy, savvy, and candor through ardently wrought language, these stories are gifts that seduce, devastate, and shine.

Kuzmich was born in Armenia and raised in the Los Angeles en-clave of Little Armenia. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in West Branch, Blackbird, Ecotone, The O. Henry Prize Stories 2015, The Threepenny Review, The Massachusetts Review, The Cincinnati Review, and elsewhere. She passed away in 2017 from lung cancer.

“Life in the Armenian Community of Aleppo” book cover

“Life in the Armenian Community of Aleppo” book coverYou can now purchase “In Everything I See Your Hand” from the IALA Bookstore powered by Bookshop.

Manoug Hagopian’s memoir in stories, “Life in the Armenian Community of Aleppo,” describes Armenians’ joys, griefs, and daily efforts to survive after they fled the 1915 massacres in a land that accepted them with open arms.

The writer shows that Armenians who arrived in Aleppo at the turn of the twentieth century did not stay idle as refugees, but continued their lives as they did in the Armenian-populated cities, towns, and villages they were born in. Their offspring then carried the torch of their parents and built their lives in Aleppo and other countries that they migrated to. Today, hardly any country in the world does not bear the mark of Armenians.

Hagopian was born in Aleppo, Syria, in 1954. At sixteen, he moved to Beirut, Lebanon, and then to the United Arab Emirates, where he worked at the offices of various international companies. Hagopian and his late Cypriot wife, Rita, had two sons. Today, he lives with his sons in Nicosia, Cyprus.

The writer worked as a translator for about twenty-five years at various companies in the UAE and Cyprus. He originally wrote his book in the Armenian language and used his skills as a translator to translate his work into English. Both versions are available now.

Manoug Hagopian

Manoug Hagopian

Hagopian’s next book, “Life Within the Armenian Community of Cyprus,” in Armenian, will be published soon, to be followed by the English version. He will publish “Life Within the Armenian Community of the UAE,” both in Armenian and English.

You can now purchase “Life in the Armenian Community of Aleppo” on Amazon, and its original publication on Barnes & Noble.

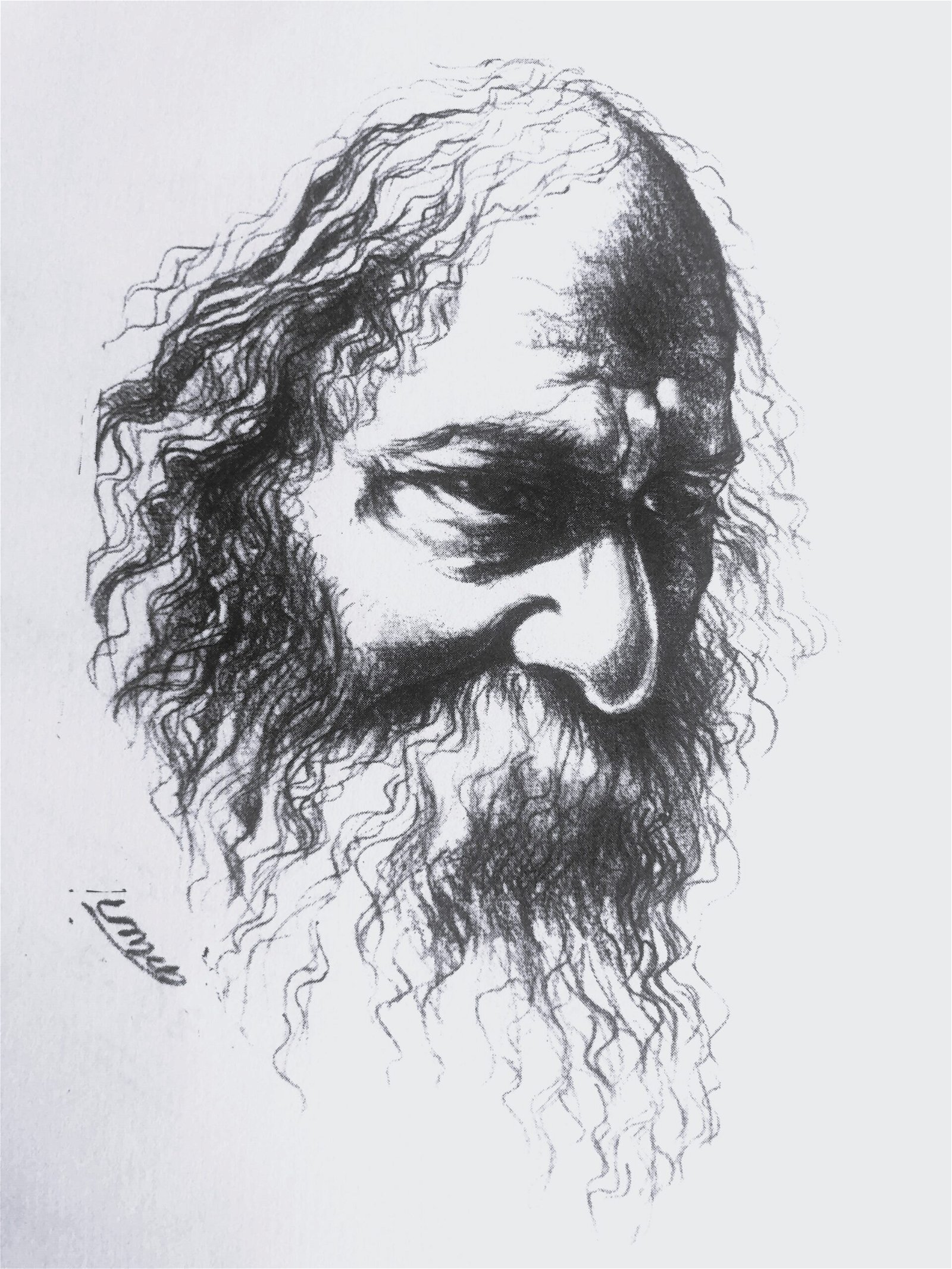

Rabindranath Tagore in remembrance of VV, 1985. Charcoal, 15×22 cm

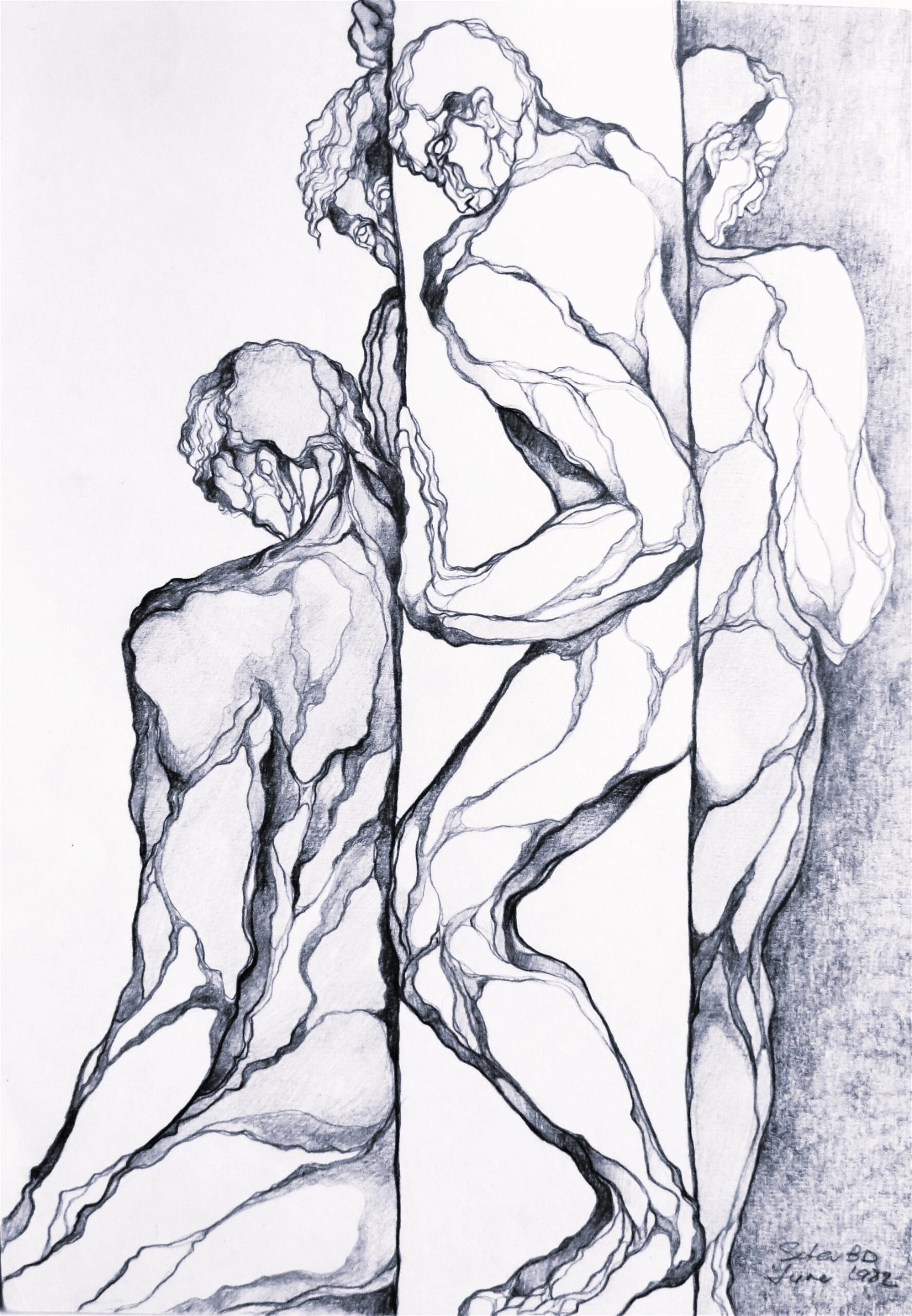

Rabindranath Tagore in remembrance of VV, 1985. Charcoal, 15×22 cm  The shelter, Beirut, 1980. Ink, 46.5×34.5 cm

The shelter, Beirut, 1980. Ink, 46.5×34.5 cm  The comrade, Beirut,1980. Pencil, 47×40.5 cm

The comrade, Beirut,1980. Pencil, 47×40.5 cm  Qasf (bombardment), Beirut, 1981. Pencil, 48.5×30 cm

Qasf (bombardment), Beirut, 1981. Pencil, 48.5×30 cm  Dialectics, Beirut, 1981. Pencil, 29.5×21 cm

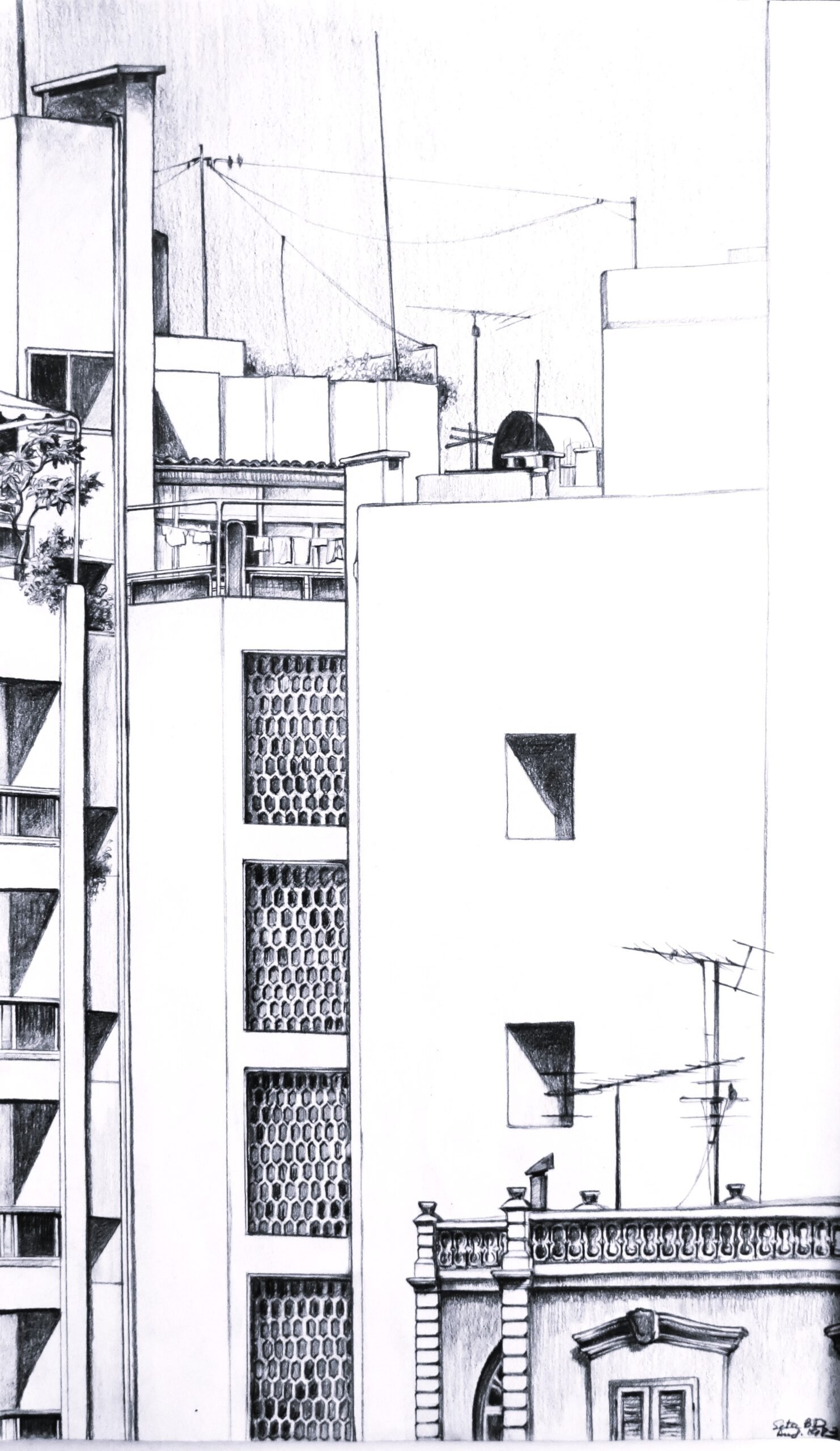

Dialectics, Beirut, 1981. Pencil, 29.5×21 cm  Window 2, Beirut, 1982. 41.5×25 cm

Window 2, Beirut, 1982. 41.5×25 cm  Situatedness, Beirut, 1985. Pencil, 36.5×25.5 cm

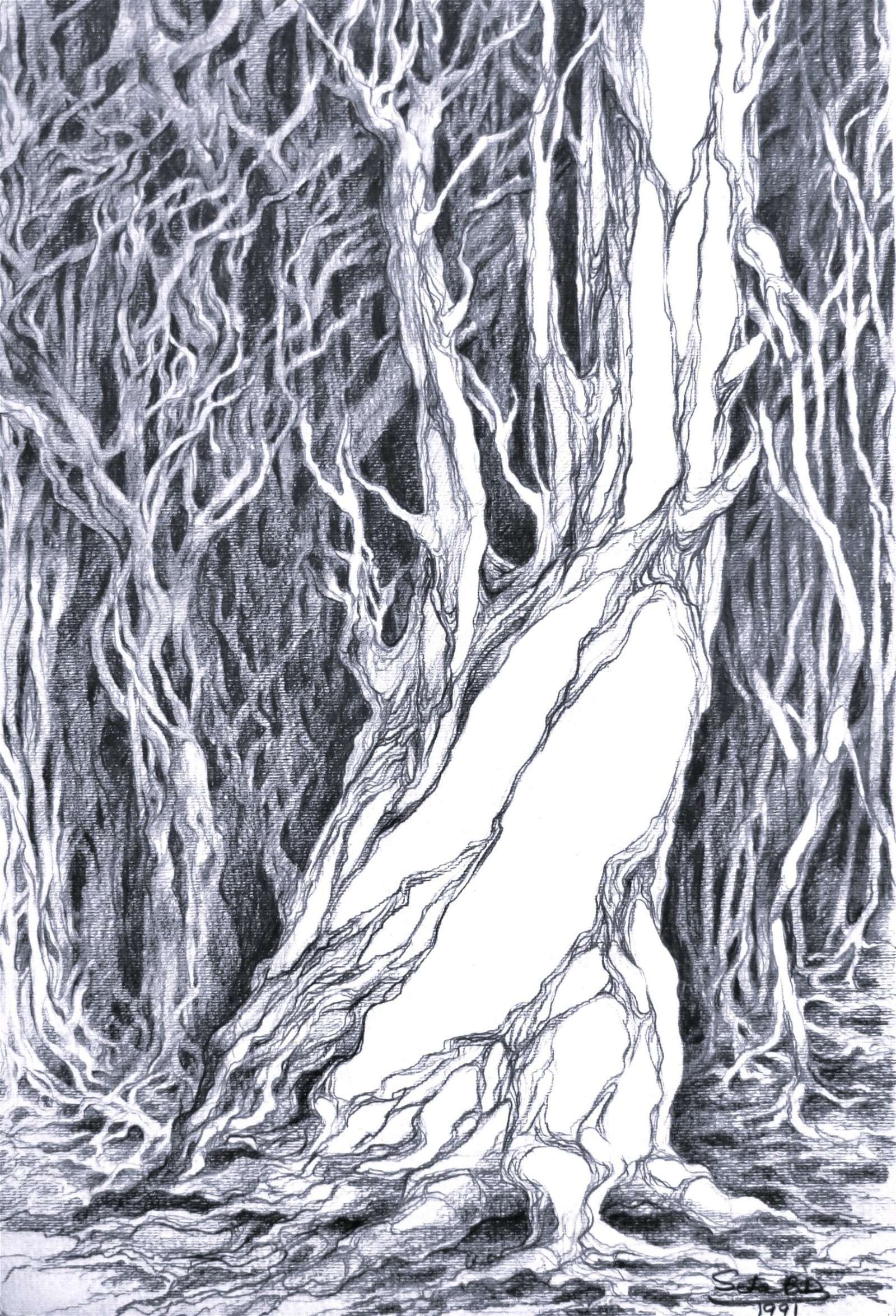

Situatedness, Beirut, 1985. Pencil, 36.5×25.5 cm  The banyan tree of AUB, Beirut, 1991. Pencil, 31.5×21.5 cm

The banyan tree of AUB, Beirut, 1991. Pencil, 31.5×21.5 cm